During World War I, the bustling streets of Manhattan’s Union Square offered an extraordinary sight. The USS Recruit (1917), a wooden landship built for the US Navy, stood prominently in the heart of the area. While it never sailed the oceans or faced enemy fire, this unconventional vessel functioned as a training platform for new recruits and boosted enlistment numbers to support the war effort. Though it remained in place for just three years, it successfully fulfilled its mission.

Conception of the USS Recruit (1917)

When the United States entered the First World War, the Navy needed to recruit more men. In New York City, Mayor John P. Mitchel pledged to recruit 2,000 new sailors for the war effort, but struggled to surpass 900 volunteers.

“The recruitment numbers in 1916 had been a major embarrassment to the New York City mayor at the time, John Mitchel,” Scot Christenson, the director of communications at the United States Naval Institute, tells The New York Times. “So he realized that if he could not bring people from the middle of New York to a ship, he could bring a ship to the middle of New York.”

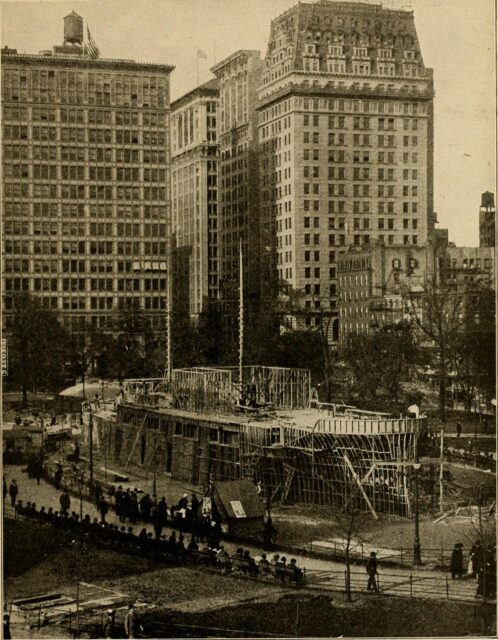

Needing to spark interest in potential candidates, Mitchel devised a plan to build a wooden landship in the near-perfect likeness of active-duty battleships. Following the direction of the Mayor’s Committee of National Defense, the USS Recruit was built and “launched” on May 30, 1917, in the heart of Manhattan’s Union Square.

Sailors were stationed aboard the USS Recruit (1917)

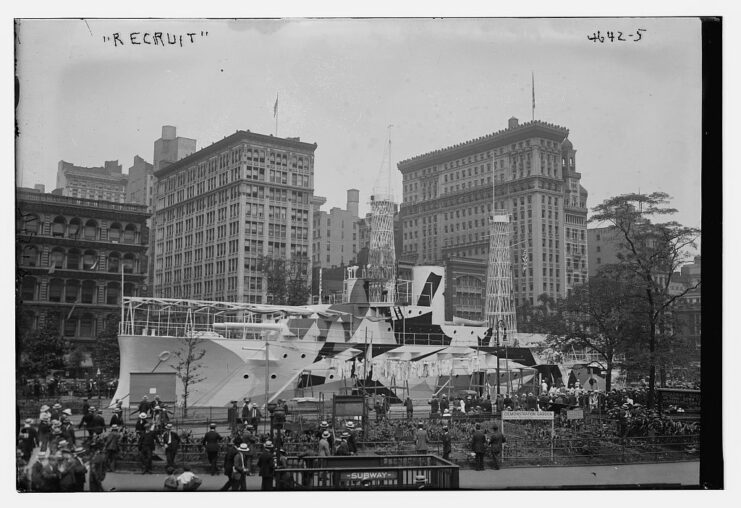

As detailed in an article published by The New York Times on March 27, 1917, “Measuring 200 feet from stem to stern and forty feet beam, the Recruit has been built to offer much-needed quarters for both the Navy and Marine recruiting forces.” Equipped with a conning tower, two tall cage masts, and a faux smokestack, the wooden battleship had a remarkably realistic appearance. Inside, the vessel included a wireless station, officer’s quarters, cabins, and medical examination rooms.

A key feature of the USS Recruit was its function as a fully operational naval ship—though it was stationed on land rather than water. As an officially commissioned ship, it was placed under the command of Acting Capt. C.F. Pierce and manned by a crew of 39.

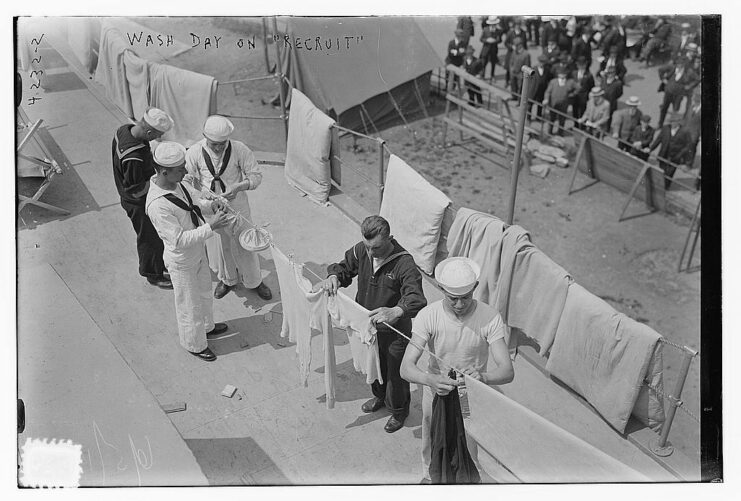

Life aboard followed a normal routine. Sailors began their day at 6:00 AM, performing tasks such as scrubbing the deck, doing laundry, and completing other expected duties. They also stood guard over the Recruit, which provided opportunities to engage with civilians. In the evenings, her searchlights were illuminated, giving Manhattan the ambiance of a bustling harbor.

‘Arming’ the land-based battleship

In keeping with accuracy, the USS Recruit was “armed” with weaponry that would’ve been equipped by other ships, just all of it was made from wood. She had three twin turrets containing six imitation 14-inch guns as her main battery and 10 five-inch guns in casemates, which served as anti-torpedo boat weapons. Two one-pound saluting gun replicas were also crafted, rounding out Recruit‘s overall “armament.”

At one point during the First World War, the Women’s Reserve Camouflage Corps painted Recruit, to give the vessel a more realistic appearance.

As Christenson explains, “For part of its existence, it was painted in vivid colors of pink, green, blue, black and white, in geometric patterns – squares and rectangles. That color scheme and pattern are called dazzle camouflage, and it was commonly used back then to help disguise the size, speed and distance of a ship, which is information a submarine would need to launch a successful torpedo attack against it.”

USS Recruit (1917) hosted social events

Beyond her regular operation as a naval ship, the USS Recruit also allowed public tours. The public could walk around the vessel and get an idea of the kinds of activities performed by sailors, and they could also ask about the Navy itself. Allowing everyday citizens to immerse themselves in life aboard a battleship certainly helped raise interest in joining the war effort.

Recruit also served as a space for notable events in New York City. Liberty Bond drives were held aboard the vessel to raise funds for the war effort, and entertainment-oriented outings were held, as well, including vaudeville performances, dances and boxing matches. The ship even served as a set for the 1917 film, Over There.

Additionally, a christening was held aboard Recruit, as were patriotic speeches from organizations like the Red Cross Women’s Motor Corps.

Successfully recruiting new sailors

Over the course of her time in Union Square, the USS Recruit did exactly what she was intended to; New York City’s original recruitment total of 900 multiplied drastically, thanks to the wooden battleship.

After several years of showcasing life in the Navy, the metropolitan area had managed to recruit an impressive 25,000 sailors for the service, enough to man 28 Nevada-class battleships.

USS Recruit (1917) ‘sets sail’

When the First World War came to an end, the USS Recruit stayed put for another two years. However, as Christenson explains, “By 1920, the United States had the largest Navy in the world in terms of sailors, and there was less of a need for them with the end of World War I.” As such, the ship’s flag was lowered on March 16, 1920, and she was decommissioned and dismantled.

At first, the city planned to rebuild Recruit in Coney Island‘s Luna Park for continued use as a recruiting depot for the Navy, but when the time came, this never happened. “The plan was to move the Recruit to Coney Island. But the cost of moving the ship ended up being greater than the value, so the ship was dismantled and the materials were likely repurposed,” Christenson says.

Are you a fan of all things ships and submarines? If so, subscribe to our Daily Warships newsletter!

More from us: USS Wisconsin (BB-64): The American Battleship That ‘Lost Her Temper’ In Korea

Unable to justify the high costs, Recruit was never reassembled. While the exact fate of her materials is unknown, it’s most likely they were dispersed and used in other local projects.