The man who led the Japanese aerial attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, might be the last person you’d expect to become a Christian evangelist—yet he did. Capt. Mitsuo Fuchida’s experiences during the Second World War profoundly impacted him, ultimately guiding him toward religious conversion in the postwar years.

Mitsuo Fuchida’s early life

Mitsuo Fuchida was born in what’s now the city of Katsuragi, Japan on December 3, 1902. At only 19 years old, he enlisted in the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN), attending the academy in Hiroshima. He graduated as a midshipman, and was quickly promoted through the ranks, becoming a lieutenant by December 1930.

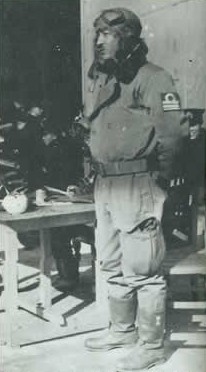

Although part of the IJN, Fuchida had a particular interest in flying. He became a specialist in horizontal bombing and was tasked with teaching other airmen the technique. He was assigned to the aircraft carrier Kaga in 1929 during the Second Sino-Japanese War, before being transferred to the Sasebo Air Group.

On December 1, 1936, Fuchida was promoted to lieutenant commander and accepted into the Naval Staff College. When WWII broke out, he was serving as the commander of the air group aboard Akagi and had logged an impressive 3,000 flying hours.

Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor

Just months before the attack on Pearl Harbor, Mitsuo Fuchida was promoted to commander, tasked with leading the first wave of aerial forces against Oahu’s northern side in Hawaii.

At 7:40 AM on December 7, 1941, he launched the assault from his Nakajima B5N2, sending up the “Black Dragon” flare to signal his men to begin the attack. Fearing the Mitsubishi A6M Zero pilots hadn’t seen the first flare, he launched a second. However, the bombers interpreted this as their cue to attack, which they promptly did.

Fuchida’s aircraft was flown by Lt. Mitsuo Matsuzaki, and they joined the formation. The air assault succeeded, and Fuchida broadcasted the infamous phrase, “Tora! Tora! Tora!” to inform the Akagi’s crew that the first wave had achieved its mission.

Instead of immediately returning to the aircraft carrier, Fuchida remained in Hawaiian airspace to oversee the second wave’s success as well. Upon his return, he discovered his aircraft had sustained 21 flak hits and confirmed that the target American ships had been destroyed.

Mitsuo Fuchida’s service throughout the remainder of World War II

His command during the attack on Pearl Harbor made Mitsuo Fuchida a national hero in Japan. He went on to serve in many other battles throughout the Second World War, including leading the first wave of aircraft against Darwin, Australia on February 19, 1942. He also led a series of air assaults against the Royal Navy in British Ceylon a few months after that, in what British Prime Minister Winston Churchill called “the most dangerous moment” of the conflict.

Fuchida served aboard Akagi until she was scuttled during the Battle of Midway. He didn’t fly that day, as he was recovering from appendicitis. When the aircraft carrier was attacked, he was forced to evacuate the bridge with his fellow officers by climbing down a rope. At that very moment, however, an explosion went off, throwing him to the deck below. He suffered two broken ankles.

Searching for meaning following the Second World War

After recovering from his injuries, Mitsuo Fuchida spent the remainder of the the Second World War in Japan as a staff officer, before being promoted to captain on October 1944. As a high-ranking officer, he was asked to travel to Hiroshima to look at the damage caused by the atomic bomb. Although everyone in his group died from radiation poisoning, he was completely fine.

Fuchida’s career came to an end when the Americans occupied Japan in November 1945. He returned to his family’s chicken farm and recalled feeling, “Life had no meaning […] I had missed death so many times and for what? What did it all mean?”

Mitsuo Fuchida finds religion

Mitsuo Fuchida’s search for meaning began, inadvertently, when he was asked to testify in a number of Japanese war crime trials. Determined to prove this was simply “victors’ justice,” he talked with former prisoners of war (POWs) to show that the Americans had treated them in the same way.

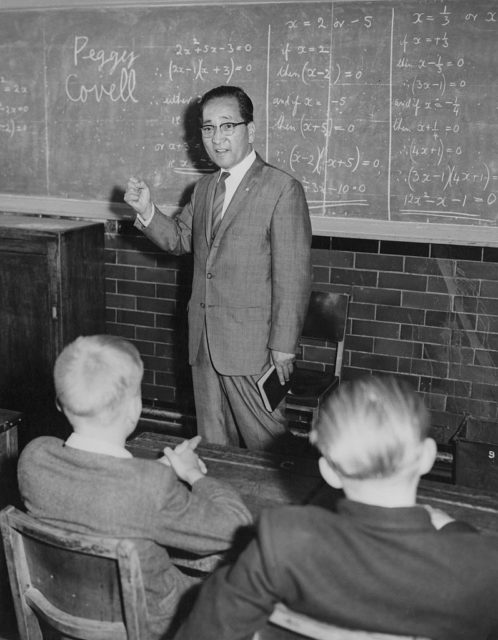

When he arrived, Fuchida discovered the flight engineer he thought had died at Midway was one of the POWs. Kazuo Kanegasaki told him they hadn’t been treated poorly and recounted a woman named Peggy Covell, who’d tended to them, despite her parents being killed by the Japanese.

This was the first moment that caused Fuchida to re-evaluate his world beliefs. The second was when he read a pamphlet written by Jacob DeShazer, who was taken prisoner following the Doolittle Raid in April 1942. DeShazer was an atheist, but after being tortured turned to Christianity.

Fuchida followed a similar path and read the Bible out of curiosity. He officially converted to Christianity in September 1949. After that, he was extremely dedicated to religion and started traveling the world as an Evangelist. He was even invited to the United States to share his story, a nerve-wracking request to make of the man who commanded the enemy aerial fleet at Pearl Harbor.

Fuchida said he was only ever welcomed warmly, telling those he met, “I would give anything to retract my actions at Pearl Harbor, but that is impossible. Instead, I will work at striking the death-blow to the giant called hatred which infests human hearts.”

Embellished stories

Aside from establishing the Captain Fuchida Evangelistic Association, Mitsuo Fuchida recounted his own story in numerous books: Midway: The Battle that Doomed Japan (1955), For That One Day: The Memoirs of Mitsuo Fuchida, the Commander of the Attack on Pearl Harbor (2011) and From Pearl Harbor to Calvary: True Story of the Lead Pilot of the Pearl Harbor attack and His Conversion to Christianity (1959).

Yet, as much as he told his story, Fuchida also received significant backlash for its accuracy. For example, the official Japanese history of Midway contradicts what he claimed. He also made comments about demanding a third wave of aerial attacks at Pearl Harbor, which were dismissed by H.P. Willmott, Tohmatsu Haruo and W. Spencer Johnson in their book Pearl Harbor as something that never happened.

Perhaps the most critical of all was Alan Zimm in his 2011 book, Attack on Pearl Harbor: Strategy, Combat, Myths, Deceptions. He called out Fuchida for retroactively changing his commands, calls and actions on the day of the attack, while blaming the mistakes he made on others.

New! Want to become a trivia master? Sign up for our War History Fact of the Day newsletter!

More from us: 33 Rare Photos of the Japanese Attack on Pearl Harbor

Fuchida never appeared to address these critiques. Instead, he spent his life recounting his experiences during the war and how they led him to find Christianity. He died in Japan on May 30, 1976 from diabetes.