As World War I raged on, the British government ran low on both soldiers and munitions. While conscription rectified the troop shortage, it only fueled the need for factory workers, leading to the decision to allow women to take up these newly-vacated roles. Known as “Munitionettes,” they kept the United Kingdom from having to drop out of the conflict.

Women are introduced into the workforce

Despite attempts to increase production by promoting overtime and recruiting older males, many munitions factories across the United Kingdom experienced worker shortages. This period was dubbed the “Shell Crisis of 1915” and prompted the government to enact legislation, allowing them more involvement in the industry.

The Munitions of War Act of 1915 introduced regulated wages, hours and working conditions within the country’s munitions factories. However, a stipulation was the mandatory inclusion of women in the workforce to help mitigate the labor shortage caused by male volunteer and conscription within the military.

The primary concern of trade unions was that introducing women would affect men and their pay upon their return from the frontlines. There was also uncertainty over the capability of women to accomplish the job. To qualm these worries, the act declared the introduction of “semi-skilled or female labour shall not affect adversely the rates customarily paid for the job” or reduce a male worker’s expected pay.

Meet the Munitionettes

It’s estimated that approximately one million women were working within the munitions industry by the middle of 1918. While many had previous factory experience, few had built munitions, and the majority took the opportunity to escape domestic work.

The women working in munitions factories were known as “Munitionettes.” They were supervised by members of the Women’s Police Volunteers (WPS), a national voluntary organization. Conditions differed from factory to factory – some offered canteens and bathrooms, while others didn’t.

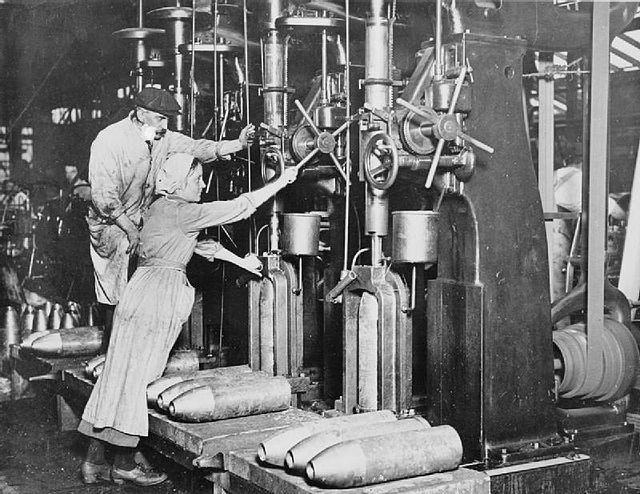

Munitionettes carried out a wide range of jobs, including operating machinery; filling, painting and stacking shells; filling bullets; weighing powder; assembling detonators; lacquering fuses; and making shell cases. It was repetitive work, but they could not lose focus, as their work was regularly checked to ensure it met quality standards.

Munitionettes were subjected to long working hours. Shifts typically ran 12 hours, six days a week, and could occur anytime, as factories often ran 24/7, in order to meet demand. It was common for them to work overtime, with little-to-no breaks.

Instead of wearing skirts, Munitionettes wore a uniform pants suit. They were also given dog tags for identification, in case they fell casualty to an explosion while on the job.

Hazardous and low-paying job

Working conditions at munitions factories varied, but the majority had strict regulations in place to reduce workplace incidents, primarily around metal-based personal clothing and accessories. Workers wore wooden clogs, instead of metal shoes, to reduce the risk of explosion-triggering sparks, and metal jewelry and matches were prohibited.

A primary hazard was TNT poisoning. Munitionettes worked with hazardous chemicals daily, without any proper protection or ventilation, and TNT was the worst. Long-term exposure caused liver failure, anemia, digestive issues and chest infections. The nitric acid also caused workers’ skin to turn yellow, leading to the nickname, “Canary Girls.” These effects were temporary and could be passed on to newborns if a woman was pregnant.

Explosions were another hazard they had to contend with. There were several explosions at factories across the United Kingdom during the First World War, and the worst occurred at the National Shell Filling Factory, in Chilwell. A total of 134 workers died, while another 250 were injured.

Despite attempts to lessen outrage regarding wages, the issue continued to be a hot topic throughout the conflict. Female workers were paid less than half that of their male counterparts. There was also no standard rate, meaning many lived below the level of a living wage. There was even a rule that stated women couldn’t leave for higher-paying jobs without the explicit permission of their previous employer, a practice that ended in August 1917.

Munitionettes football

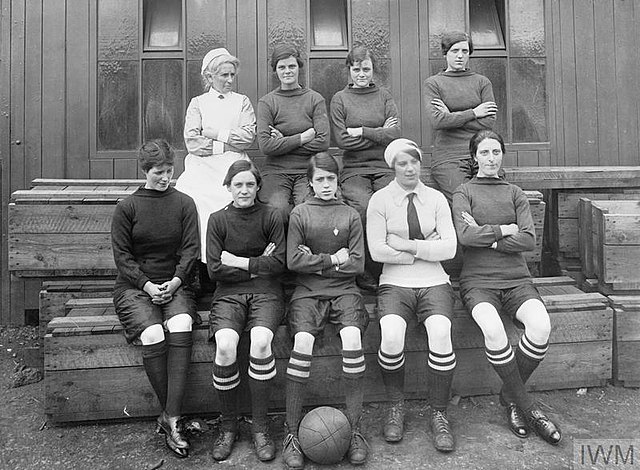

Women who worked in munitions factories engaged in a variety of extracurricular activities. Social clubs, bands, debate groups and theatrical societies were popular among Munitionettes, much to the encouragement of factory management, who saw it as a way to keep both morale and productivity up.

The most popular form of entertainment was football. Without men, the introduction of women’s football was met with fanfare from workers and the public. There was even a tournament – the Munitionettes’ Cup – that took place in the northeast between different munitions teams during the 1917-18 season.

Fueling the women’s suffrage movement

By the end of the Great War, over 200 women had lost their lives due to their work in munitions factories, and it’s estimated that roughly 80 percent of munitions used by the British Army were being produced by women. Despite this, many lost their positions when soldiers returned home, and several left the workforce having never received equal pay to their male counterparts.

More from us: Lumber Jills: The Women Who Made Up Britain’s Timber Corps

Want War History Online‘s content sent directly to your inbox? Sign up for our newsletter here!

While women were largely relegated back to domestic life, their work in factories and other previously held male positions helped demonstrate their capabilities and worked to further promote the women’s suffrage movement. It also changed the way they were viewed in society, giving them greater freedom and the ability to travel.