The Fritz X, also referred to as the Ruhrstahl SD 1400 X or Kramer X-1, marked a big leap in German anti-ship technology. Engineered to boost armor penetration, it was further refined to increase its accuracy and combat effectiveness, achieving remarkable success in action. Nonetheless, despite these advancements, the Fritz X had notable shortcomings, especially its susceptibility to attacks by Allied aircraft.

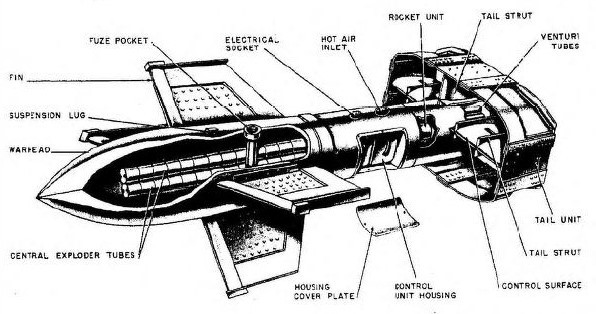

Modified PC 1400

Conceived by Max Kramer and manufactured by Ruhrstahl AG, the Fritz X came from the PC 1400 (1,400 kg) bomb. Weighing 3,450 pounds, it had a formidable 710-pound warhead that was capable of penetrating up to 28 inches of armor when deployed between 18,000 and 20,000 feet.

In 1940, various iterations were made to ascertain the optimal design. The X-2, engineered for higher speeds and equipped with an infrared homing device, saw its development halted, with only a single unit produced. Conversely, the X-3, which was larger and heavier in comparison, boasted impressive speeds of up to 900 MPH. Nonetheless, the X-1 emerged as the preferred choice, due to its streamlined operation and developmental simplicity.

By 1941, the Luftwaffe began rigorous testing of the missile. Two years later, the project advanced to the manufacturing phase.

Fritz X specs

The Fritz X boasted an advanced aerodynamic design and employed the sophisticated Kehl-Strasbourg joystick radio-control guidance system. Its tail featured a complex twelve-sided structure supporting four streamlined fins, two of which were extended and fitted with spoilers to allow precise course adjustments. Stability was maintained by dual gyroscopes, with asymmetrical cruciform wings positioned at the front.

These missiles were launched from both the Dornier Do 217K-2 and the Heinkel He 177A Greif, as bombardiers tracked their descent using tail flares. The radio-controlled spoilers enabled the Fritz X to execute highly accurate maneuvers, assuming Allied radio jamming did not disrupt the signal.

Success in the Mediterranean Theater

The Fritz X made its debut in combat on July 21, 1943, during a raid on the Port of Augusta in Sicily. At that time, no confirmed hits were reported, and the Allies remained largely unaware of the Germans’ use of radio-guided missiles. However, the Fritz X achieved its most notable success in a subsequent attack on the Italian fleet in September 1943.

Following the arrest of Benito Mussolini, the Italian government entered into negotiations with the Allies. On September 8, the Supreme Allied Command in Europe announced the signing of an armistice. A plan was devised to transfer the Italian naval fleet to Allied ports in Tunisia and Malta. However, the Germans quickly caught wind of the plan and devised their own strategy to intercept the convoy, aiming to prevent the ships from reaching their intended destinations.

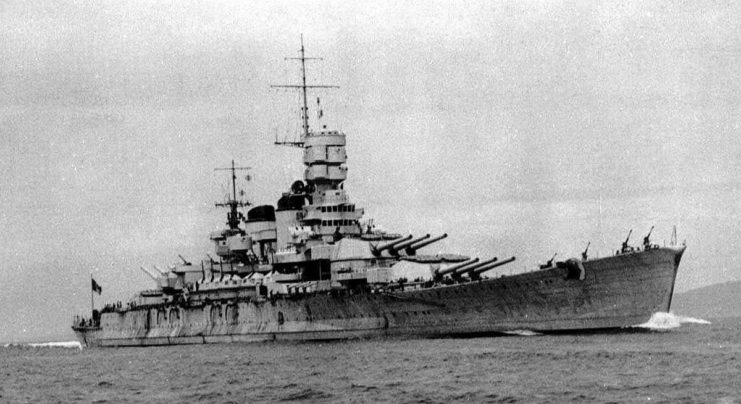

Sinking of Roma (1940)

A squadron composed of three battleships—Roma (1940), Vittorio Veneto, and Italia (1943)—accompanied by six cruisers and eight destroyers, sailed along the western coast of Corsica, heading toward Sardinia and Tunisia. Around midday, six Do 217K-2 aircraft from Gruppe III of Kampfgeschwader 100 Wiking approached the formation, each armed with a single Fritz X missile.

The most notable event was the sinking of the Italian flagship Roma. A Fritz X missile struck the battleship’s starboard side, detonating beneath her keel. The explosion inflicted catastrophic damage, flooding Roma‘s boiler and engine rooms and rendering two of her four propeller shafts inoperable. This loss of speed, compounded by a series of electrical fires, further exacerbated the crisis.

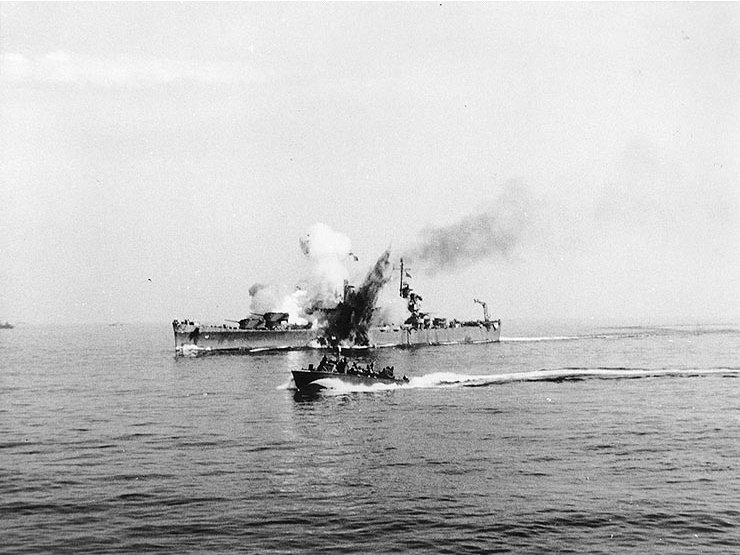

Fritz X missiles sink the HMS Spartan (95) and others

Just seven minutes later, another Fritz X hit the Roma, this time detonating in her forward engine room and causing a catastrophic magazine explosion. The force of the blast killed Vice Adm. Carlo Bergamini, the ship’s captain, and 1,393 crew members. Within 30 minutes of the first hit, Roma split in two and capsized.

In the days that followed, Luftwaffe pilots continued to deploy Fritz X missiles, sinking the British cruiser HMS Spartan (95) and destroyer Janus (F53), as well as several merchant ships in the area. They also inflicted severe damage on the British warship HMS Warspite (03) and cruiser Uganda (66), along with the American light cruisers USS Philadelphia (CL-41) and Savannah (CL-42).

The Fritz X made German aircraft vulnerable

Although the Fritz X initially showed promise, its shortcomings soon became clear. Bombers had to maintain a straight and level flight path while carrying the missile, and after releasing it, they needed to decelerate quickly, relying on visual guidance to ensure accuracy.

Aircraft equipped with the Fritz X became easy targets, a vulnerability the Allies quickly capitalized on. The most effective defense against German aircraft carrying the missile was Allied fighter planes, which prevented the bombers from maintaining steady flight. Additionally, generating smoke effectively obscured the missiles, making guidance more difficult for the bombardiers.

Moreover, the Allies swiftly implemented electronic countermeasures to disrupt radio signals, greatly increasing the challenges faced by the German forces.

Fritz X failed to meet the Luftwaffe‘s expectations

More from us: The German V-1 ‘Buzz Bomb’ Was Developed to Terrorize the British Public

New! Want to become a trivia master? Sign up for our War History Fact of the Day newsletter!

Originally, the plan aimed to manufacture 750 Fritz X missiles monthly. However, from April 1943 until the program’s conclusion in December of the following year, only 1,386 were produced, with 602 allocated for training and testing purposes. Moreover, the missiles failed to meet the Luftwaffe‘s expectations for accuracy, striking their targets merely around 20 percent of the time.

Despite its shortcomings, the Fritz X served as a precursor to the development of future spoiler-controlled missiles.