Before John F. Kennedy was the 35th President of the United States, he was a lieutenant in the US Navy during World War II. During his time in the Navy, an incident occurred involving Kennedy, PT-109 and a Japanese destroyer, and it was from this collision that Kennedy Island received its name.

Encounter with Japanese destroyers in the Blackett Strait

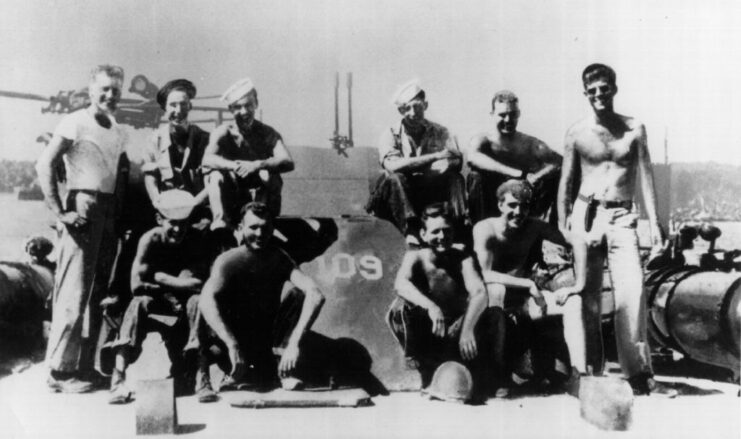

PT-109 was one of 15 patrol torpedo (PT) boats stationed in the Blackett Strait. It was also the boat that John F. Kennedy was assigned to. The vessels had been sent to the area in an attempt to disrupt the Japanese supply convoy, which ran through the strait.

The Americans encountered four Japanese destroyers: three were acting as transport vessels, while the fourth was an escort. The PT boats launched 30 torpedoes at the convoy, but failed to damage any of the ships. While none of the American boats suffered damaged, some had depleted their stock of torpedoes and were ordered to return to port

The vessels that still had torpedoes remained, hoping to have another go at the destroyers. One of them was PT-109, which opted to rendezvoused with PT-162 and PT-169. There was a fourth, but her crew had gone to investigate a blip on the radar. The three remaining boats spread out to create a line across the strait, but nothing occurred until 2:30 AM on August 2, 1943.

Suffering damage from the Japanese destroyer Amagiri (1930)

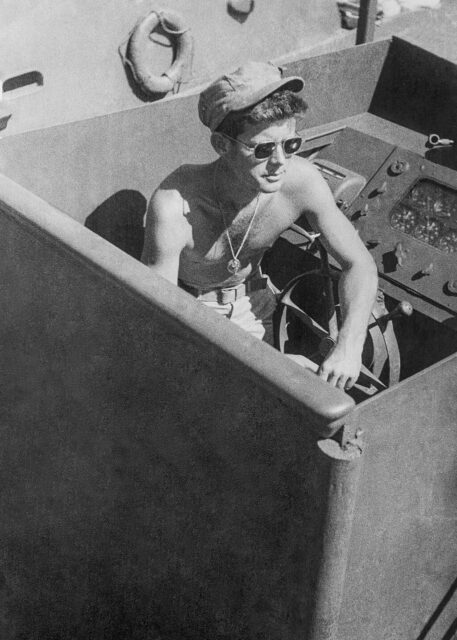

Three hundred yards from PT-109, a Japanese destroyer came through the darkness. At first, John F. Kennedy thought the shape was one of the other PT boats. When he saw that it was a destroyer, he attempted to turn his vessel to bring the torpedoes in line, but his efforts were made difficult by his decision to fire up just one of PT-109‘s three engines.

Kennedy’s maneuvers came too late, as the destroyer Amagiri (1930) ripped through the starboard aft side of PT-109. What’s more, the Japanese vessel didn’t even realize that the collision had occurred.

Most of PT-109‘s crewmen were knocked into the water by the impact, with two losing their lives. Engineer Patrick H. McMahon was below deck. While he’d escaped, he had been injured by exploding fuel. The rest of the crew were ordered to abandon ship by Kennedy, who feared PT-109 would burst into flames.

The ignited fuel was eventually dispersed by waves from Amagiri, and Kennedy ordered his men back to the wrecked boat. Once they reached PT-109, they needed to locate the remaining crew members. Four were able to swim back to the wreckage on their own. McMahon was too injured, so Kennedy swam out to him and Charles A. Harris. Using a life-vest strap, he towed McMahon to the boat while encouraging Harris.

Making a tough decision

The rest of the crew made it back to PT-109, where they considered their situation. It wasn’t good, as the men were exhausted, some were injured and others had become sick from the fuel fumes.

The other PT boats were nowhere to be seen, and the crew was afraid to use flares, as they could draw the attention of the enemy. While PT-109 was still floating, she was taking on water and would soon capsize. The only option was to abandon ship and make their way to land.

The distance to the closest inlet was three and a half miles, which wasn’t daunting to John F. Kennedy – he’d been on the Harvard swim team – but not all of the crewmen were strong swimmers. In fact, two couldn’t swim at all.

John F. Kennedy and his comrades abandon ship

The two men who couldn’t swim were tied to a plank that the other crew members towed. John F. Kennedy arrived at the island known as Plum Pudding first, but was exhausted and had swallowed so much seawater that he had to be helped to the beach by the man he was towing.

However, his night was far from over. A passing Japanese barge prompted Kennedy to swim back out and look for the other PT boats in the area. Making his way to Ferguson Passage, he treaded water for an hour without seeing other American vessels. On the return journey, he had to stop at another island to rest, before getting back to Plum Pudding.

The next day, Kennedy and his men set out for Olasana Island, hoping to find supplies, but the coconuts there sickened some of them. Leaving the crew on the island, Kennedy and George Ross went to Naru Island, where there was a wrecked Japanese ship on the beach, along with some supplies.

There were also two men at the wreck, who were identified as islanders. Kennedy tried to hail them, but they became frightened and left in a canoe.

The future president took a canoe he’d discovered into Ferguson Passage that night, but was unable to see any friendly vessels. He made his way back to the crew on Olasana with the supplies, leaving Ross on Naru. There, he found that the two men from earlier had made contact with the rest of the men and had identified themselves as islander scouts for the Allies.

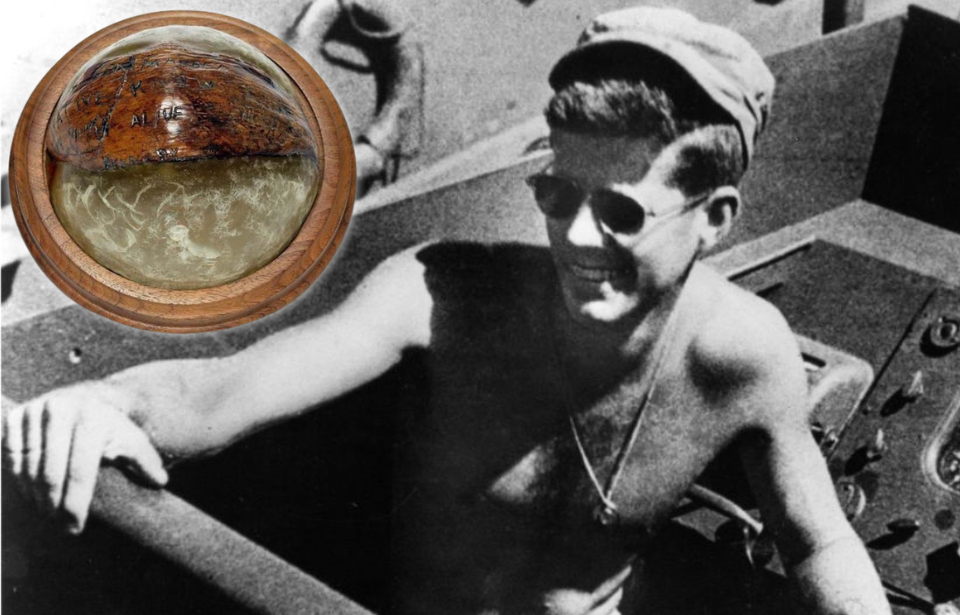

John F. Kennedy’s coconut message

The next day, John F. Kennedy and the two men made their way back to Naru, where they showed him how to scratch a message into a coconut. It read, “NAURO ISL COMMANDER … NATIVE KNOWS POS’IT … HE CAN PILOT … 11 ALIVE NEED SMALL BOAT … KENNEDY.”

The message was sent with the pair, but Kennedy and Ross didn’t wait patiently. Taking a two-man canoe given to them by the islanders, they entered Ferguson Passage, hoping to find help. The rough conditions nearly sank the canoe and the two of them barely made it back to Naru.

The next day, eight islanders arrived with supplies, food and a message from Lt. Arthur R. Evans, the coast watch commander of the New Zealand camp, who instructed Kennedy to make his way to his post on Gomu Island. After ensuring his men were fed, the islanders hid Kennedy under palm fronds and made their way to Gomu. Six days after PT-109‘s loss, he made it, but a rescue mission still had to be planned. He insisted on being part of it, and it was successful.

The leadership and bravery Kennedy displayed led to him being awarded the Navy and Marine Corps Medal, as well as the Purple Heart, making him the only US president to receive either honors. When asked about this later in life, he famously replied, “It was involuntary. They sunk my boat.”

More from us: No legs, No Problem: The Incredible Story of RAF Ace Douglas Bader

Want to become a trivia master? Sign up for our War History Fact of the Day newsletter!

The incident also resulted in Plum Pudding being renamed “Kennedy Island.”