The first American aircraft carrier was commissioned 100 years ago and onboard was a crew of small, winged comrades who proved their service was invaluable in battle: pigeons. These beaked creatures were bathed, trained and fed by a US Navy sailor whose job was solely to care for them.

Pigeons have a long history of military service

Pigeons provided invaluable service long before they were brought aboard the USS Langley (CV-1). Their use as messengers dates back as far as ancient Rome, when they were used to deliver the standings of chariot races. They also had an earlier career with the Navy, trained first at the Naval Academy in Maryland and, later, through the Naval Pigeon Messenger Service. The latter was established in 1896 and saw pigeons ferry messages from ship to shore.

Wireless telegraph machines were brought aboard vessels in 1902, leading the Navy to disband the Naval Pigeon Messenger Service and auction off the birds. However, when World War I began, they were brought back in other capacities, conducting homing missions with naval aviators.

A new naval role: Quartermaster (Pigeon)

The importance of having well-trained pigeons within the Navy was evident in the creation of the “pigeon trainer” enlisted rate. Naval Air Station (later Naval Support Facility) Anacostia became the largest pigeon school in the country, with some 300 birds being trained there, establishing a job opening requiring qualified pigeon trainers.

The official title of these trainers was Quartermaster (Pigeon), but QM(P) sailors were more often known as “pigeoneers.” Training pigeoneers was serious business. Trainees had to undergo six to 12 months of schooling before they could be considered for work at a naval air station’s pigeon loft.

They learned such things as when to bathe the birds, what to feed them, how to properly hold them and how to build rapport, on top of conducting regular inventories of the pigeons – particularly those who were breeding. They were also taught how to clean the birds’ perches and nesting boxes, which were well-equipped with running water and electricity to provide comfort for the valuable, winged passengers.

Onboard the USS Langley (CV-1)

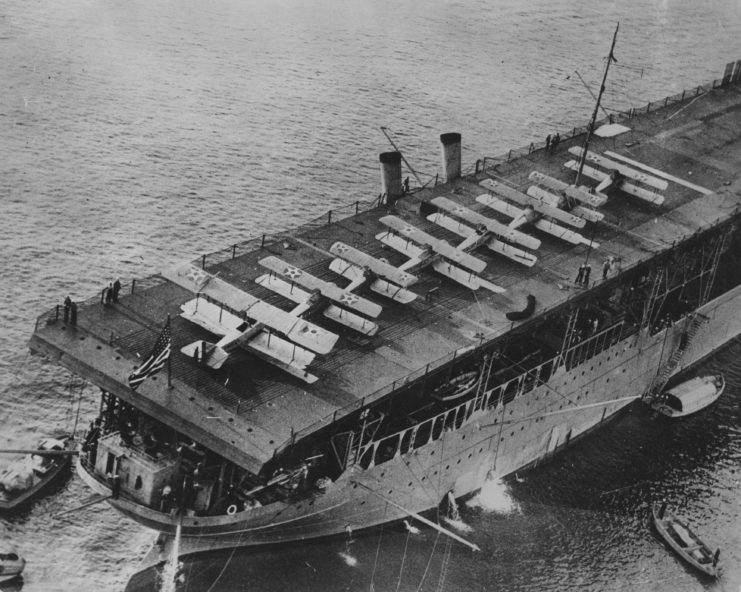

In 1919, the USS Langley was known as the USS Jupiter (AC-3). That year, the decision was made to modify her into an aircraft carrier. She was equipped with large steel girders and a wooden flight deck, and, in all, she was rather ugly. The vessel was nicknamed the “Covered Wagon,” as she closely resembled one from the days of the Wild West.

Rear Adm. Jackson Tate, who served on Langley early in his military career, remembered the elaborate area where the pigeons could be found. He recalled how the pigeon house was built on the aircraft carrier’s stern side – more accurately, between the ship’s 5-inch/51 guns – and was equipped with food storage, nesting, training and trapping components. The extensive effort to support these little passengers proved they were a valuable part of the crew.

When the guns were fired for testing, the intense sounds bothered the birds. They became so upset that the QM(P) forcefully argued for their protection against such distressing sounds, though they may not have been successful in their efforts. However, the area that originally housed the pigeons was eventually rebuilt into the executive officer’s quarters.

The pigeons go AWOL

The pigeons were released a few at a time to allow for them to stretch their wings and get some exercise. Generally, the birds knew to return to their lofts, especially while out at sea. However, when the USS Langley anchored, they tended to fly away. One day, the entire flock of pigeons was released while the aircraft carrier was anchored off Tangier Island and not one of them returned to the carrier.

All of the pigeons returned to the Norfolk Naval Shipyard in Virginia, where they had been trained during Langley‘s conversion. The pigeoneer was flown there and spent the night catching the birds. Following this, the pigeons were never again brought out to sea. However, this didn’t mark the end of their service in the Navy, as they made significant contributions to Allied efforts in World War II.

Are you a fan of all things ships and submarines? If so, subscribe to our Daily Warships newsletter!

More from us: The USS Barb Compiled One of the Most Outstanding Records of WWII

Pigeon lofts were planned for – and constructed upon – the aircraft carriers that followed Langley, including the USS Lexington (CV-2) and Saratoga (CV-3).