It is to my constant regret that I didn’t begin my pilgrimage to the Great War battlefields until a few years into this century.

That first trip was a crazy mix of sights and emotions that included my first visit to the grave of my great uncle Leslie, whose very existence I had only recently discovered. It was a week that spawned dozens of trips as I tried far too hard to take in swathes of the Western Front without much time to draw breath.

Happily, the pace slackened and with it came something I learned to appreciate more than anything; that building a connection with the history and places I was exploring was path to true immersion into the history I sought.

I’ll be honest, I was immensely frustrated that I had missed out on the period when a great many more signs of the conflict were present. I met people who had gone over to France in the seventies who had picked up helmets and other impedimenta off the battlefield.

I was so jealous, and, undaunted, I brought back shrapnel balls, lumps of iron and other nonsense when it was still permissible to do so and, nowadays, I wonder why I bothered with such a shallow obsession.

I’ve since got rid of nearly all of it. Souvenirs are fine as things stand; but the real treasures I have are the memories of my pilgrimage and the photographs I keep.

My Uncle Les and the tens, no, the hundreds of thousands of men like him became very important to me and I never tire of learning their stories .

I have a mate whose own uncle must have been two places behind Les on the day they enlisted in 1914. If you go to the cemetery at Gommecourt on the Somme, where my friend’s uncle rests, you will see graves of other Londoners who Les would have known.

You can’t put that in a display case. I feel like I have done the right thing by Les. Lost and found within the context of my recent family history, he is never forgotten and this is, I guess, what any of us would hope for.

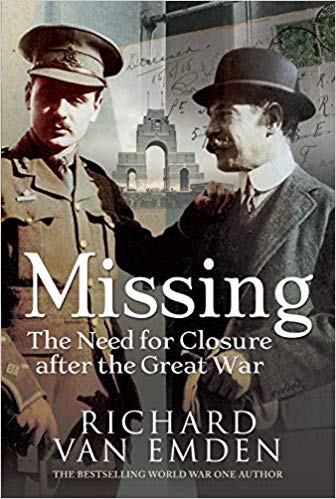

The feelings I have for these connections are enforced by this wonderful book by Richard van Emden.

He has earned a strong reputation for his previous work and is probably best known for his association with Harry Patch, the revered talisman of the trenches who was Britain’s last living combat veteran of the war on the Western Front.

Mr van Emden has done much more, though. Aside from Harry, he has brought us the lives of boy soldiers and shared the photographs and stories of the ordinary men who fought the war.

Now he turns his attention to those who never came home. We learn how Britain proposed to deal with commemorating the tens of thousands of war dead.

The author threads the bigger picture with the sad story of the death of a pilot, Francis Mond, and the quest of his mother to find his grave. The bodies of Mond and his observer were recovered after they had been shot down but were subsequently lost in what is easiest to describe as an administrative error. Mond’s mother would devote all her time in the attempt to find her son.

Her persistence was remarkable, but she enjoyed the resources ordinary people could only dream of and while this may seem unfair, it gives us an insight into the blunt reality of how the system favoured those with class and wealth.

The author succeeds in telling the saga of the search for Francis Mond while taking the reader through the process of creating the hundreds of cemeteries on the Western Front and beyond.

We learn about the effort made to build the great memorials found in France and Belgium. It was not all plain sailing and perhaps the most intense aspect is the experience of the parties of men exhuming the dead from the battlefield.

There is a telling photograph showing some of them at work, the detached expressions on their faces has a sadness to it I find it hard to describe.

Grim reality aside, this book describes a triumph of will, ingenuity, love and commitment to giving the war dead of the British empire the gratitude they deserved.

The process was never always perfect but, a century on, it is clear that the people making the crucial decisions got a great deal right.

The memorials and silent cities are with us and they will remain so in perpetuity. It is a remarkable achievement we should cherish.

“The Defenders of Taffy 3” – Review by Mark Barnes

This leaves us with Francis Mond, the everyman of Richard van Emden’s history. I hope there are enough of us interested in reading this superb book to make the big reveal a bit of a betrayal. Do the obvious thing and get yourself a copy, you will not be disappointed.

MISSING

The Need for Closure After the Great War

By Richard van Emden

Pen & Sword

ISBN: 978 1 52676 096 8