The first months of the Great War are hardly ignored by historians, but the period is wholly overshadowed by the years of trench warfare that dominate our imagery of the conflict. Those first weeks and months from the hot August days of 1914 to the end of the autumn were marked by the sort of fighting using infantry formations, cavalry and field artillery that would not have looked unfamiliar to the men who had fought over much the same ground a century earlier. But once the war of fire and movement had run its course, it was shoveled that armies needed as much as bullets.

A witness to all this was an engineer named Roger West. He had spent those weeks riding around on his motorcycle delivering messages while keeping a wary eye out for uhlans. To say he had some hair-raising adventures would be an understatement. West had been keen to get into the war at a time when tens of thousands of others had similar ideas. The British were keen to recruit experienced motorcyclists and our hero fitted the bill, but only a specific number of places were allotted in particular parts of Britain and he had some difficulty getting accepted.

Things worked out eventually and the newly minted Second Lieutenant West went off to war by motorcycle.

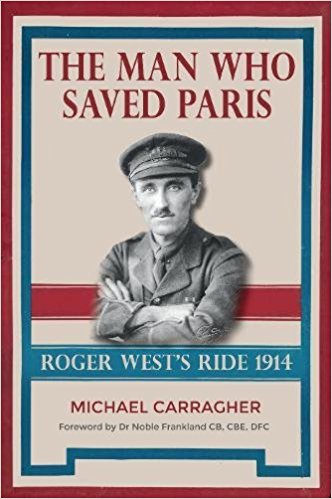

Those weeks were a torrid affair as German armies poured through Belgium in their attempt to sweep down behind Paris and knock the French out of the war before the Russians could mobilize their vast strength. The tiny British Expeditionary Force got in the way and took a serious beating, but the fighting retreat via Mons and Le Cateau and has achieved something of a mythical status for the endurance of the British regulars in the face of superior numbers of Germans who outnumbered them several times over.

The thrust of the book happens almost casually when, amid the retreat, our hero discovers a vital bridge that hasn’t been demolished. It isn’t a spoiler to say he gets the job done, because the title of the book says it all for us. That he was awarded a Distinguished Service Order says much for his achievement. The suggestion he might have received the Victoria Cross makes sense, but the rare award of a DSO to a second lieutenant shows just how important his intervention was.

Mr. West had something of a privileged viewpoint of the drama, but he tells a quite absorbing story of how he moved around the battlefield amid all the chaos and uncertainty using a degree of hindsight to set the context of what he was doing. His account is full of atmosphere and detail and he was a very good writer.

The accompanying text from Michael Carragher places us into the bigger picture of what was happening along the Western Front and further east where the Germans fear of a Russian assault before they have finished off the French is realised. I have seen a lot of books with this sort of format and it’s good to report that the balance between the writing of Mr. West and Mr. Carragher remains even, because this can take a wrong turn without discipline. The end result is this is still Roger West’s book and he has not become secondary.

Mr. Carragher’s description of the antics of Sir John French and his supposed ally General Lanrezac adhere to much of what is known of their toxic relationship. There is some humour in the fact that the British Expeditionary Force was commanded by a Francophobe called French but there the real story isn’t funny at all. John French had enjoyed a distinguished career in Britain’s colonial wars but he was utterly out of his depth handling continental warfare. He was vindictive, jealous and prone to blaming others for his own mistakes and it isn’t difficult to see why he would eventually lose his command to a cooler and more broadminded customer like Douglas Haig.

Mr. Carragher’s scene setting takes us to the horrors of the Battle of the Frontiers where Frenchmen wearing blue coats and red trousers were mown down in heaps by German artillery and machine guns. He gives us the uncertainty of the Germans as they pushed on and reminds us of how poor their intelligence was. Some Germans believed thousands of Russians brought round the North Sea would join the battle at any moment. The war crimes committed by the Germans are not overlooked, but they do not dominate the overall story.

Ultimately the book stays true to Roger West. He had a tough time in the period he was at war and ended up suffering from shell shock. But he played an important role that takes him beyond a footnote to being someone of greater interest. The war was a chapter of a life he filled with making things and exploring the Canadian Rockies after he moved to British Columbia. Our hero took a job with Paramount Pictures and worked on many movies before ending his days in Carmel, California. He spent some time sending angry letters to the British War Office attempting to get the money they owed him.

The picture of an exhausted Roger trundling around the battlefield on a worn out motorcycle is an easy one to build thanks to his vivid descriptions of those times.

This is an important book because it gives us the story of one man and does much to place him in the much, much bigger one happening all around him. Highly recommended.

Want War History Online‘s content sent directly to your inbox? Sign up for our newsletter here!

Reviewed by Mark Barnes for War History Online

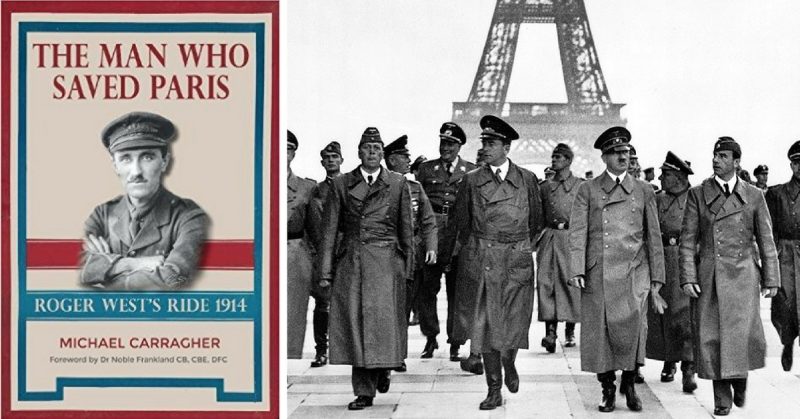

THE MAN WHO SAVED PARIS: Roger West’s Ride 1914

By Michael Carragher

Uniform Press

ISBN: 978 1 908487 05 6