I remember a warmish spring evening four years ago when I attended an event at the Houses of Parliament in London where a number of historians and political types gathered to launch Pen & Sword’s ambitious programme for the centenary period of the Great War. It was a good night, although the buffet was a bit on the thin side and I was glad I’d grabbed a burger on the way in. Amongst all the faces was a writer who asked me why I was there and I proudly told him I represented War History Online. He was distinctly unimpressed. He asked me what work I had done so I ran through a few of my achievements. He was very unimpressed. “You are nothing if you are not a published man” he assured me. “You have to write books.” I quickly passed from miffed to full on indignant but he soon left to catch a train back to I cared not where and I fell in with a few people I know who seemed less critical of my presence. But, actually, his advice – for that is what it was, proved critical to me.

It’s all about books.

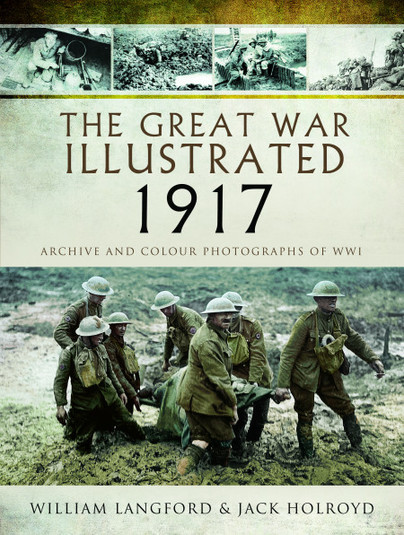

Now I am a published man and busier than ever with that aspect of my life but reviewing books remain a considerable pleasure and the process is helped with this volume from a marvellous series that has moved on to the pivotal year of 1917. Archive photography has consumed forty-one years of my working life and a product like this is bound to appeal. All the major events and a good number of leading personalities from the year in question appear here. The book avoids getting bogged down in Anglo-centricity by paying due respects to the sacrifice and endurance of France, and justly so. But it is inevitable that the activities of the British and Imperial forces would play a major part in proceedings. 1917 was, of course, the year the United States entered the conflict, a fact that can hardly be ignored.

There is so much to like here that I considered how I would construct a review without repeating myself. I gave up on that forlorn hope and have been pragmatic. So, just like those cheesy sitcoms that do montage episodes to save a bit of production cash, let’s look back to my review from 2016:

The book is short on interpretation and big on letting the reader see things for themselves. If you see something that piques your interest here, look beyond the book to other resources. It’s how history is learned and loved. Books like this are the Saturn V rocket that turns the foggy events of the past into something clearer and worth keeping. I might also say you could end up with five books of the complete series in your library that give you the Great War in about ten inches of shelf space. It depends how OCD you are about these things, I guess.

I said this for the 2015 volume:

To me, there is something quite authentic about the style. It recalls the sort of ‘picture pages’ that appeared in newspapers before World War II. They were random affairs leading the reader in all directions, but that was actually the point. Although photography had been identified as art in some enlightened quarters, to the vast majority it was still just a record, a quick look at things – not really a medium for saving moments of history. Of course, that is precisely what photography is and was – it saved moments and in age when many people got to keep it with Kodak the importance of photography was slowly beginning to be understood by a much wider audience. All this might be hard to appreciate in our age of Snapchat and selfies, but it was so.

And so on:

If you are looking for an entertaining history of the war then you will find a big slice of it in this book. The authors look beyond the photographs to the attitudes and spirit of the times to arrange things in context. This is crucial to the success of this book

I will save you from a rerun of 2014. The thing is these books have grown as they have advanced through the years of conflict but the style and spirit has remained consistent. All the elements in this book that I admire today appealed to me four years ago. There is now a colour section of colourised imagery I admit to being less keen on, but they are authentic and don’t detract from the package as a whole. My photo archive blood only runs in monochrome and I won’t make excuses.

So here you have a huge gallery of imagery from a century ago presented in a way that informs and entertains. I admit to have grown a bit jaded with the centenary experience but books like this keep the faith and I am looking forward to the finale that appears later this year. Outstanding stuff.

THE GREAT WAR ILLUSTRATED – 1917

By William Longford and Jack Holroyd

Pen & Sword

ISBN: 978 1 47388 161 7

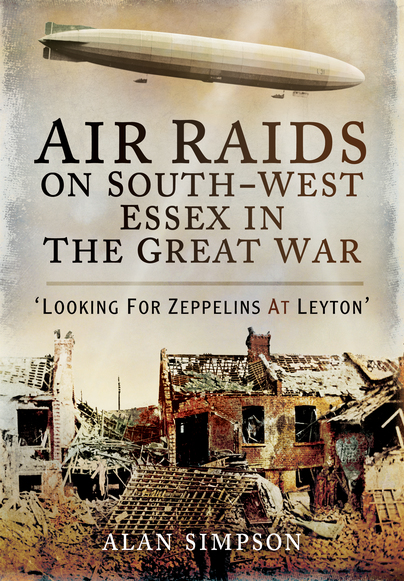

Big pictures always appeal, but there are always myriad small stories that build the complete history of tumultuous events like the Great War. This book, one I should have reviewed a good six months ago, is just such a case. Alan Simpson looks at how the air war over Britain between 1915 and 1918 impacted on the south-west corner of Essex, the county to the east of London on the north side of the River Thames. Most of the events described occurred when the Germans were attempting to attack the capital.

The first thing we take from this book is an understanding of the geography then and now. What becomes clear is how the great urban sprawl of the capital I have known all my life is a relatively recent phenomenon. Now, of course, I knew this; but it is always interesting to see things explained with care because there is so much about a city like London to be taken for granted.

The fear of Zeppelin raids was quite out of proportion and attempts to define the odds of being hit by a bomb would not wash with people for whom the spectre of modern warfare had gone from novelty to nightmare in short order. This was aided by the scale and menacing impression of the airships themselves. They were big and seemingly out of reach of Britain’s guns and aircraft. The damage they caused was hardly immense, but practically every bomb dropped by German airships was the kindling of a personal tragedy or drama. The raids had other consequences when mob mentality was applied, especially in the wake of the sinking of the Lusitania when a combination of what were seen as atrocities gave vent to anger and frustration. Longstanding businesses of German origin were attacked, although all too often the proprietors had settled in England to escape the very thing the mob were angry about. The honest truth is some of the people smashing up German property were just looters looking for opportunities.

By 1916 the British had developed aeroplanes and weapons capable of attacking an airship and this was the year some were shot down in flames. I pass a memorial at one crash site when I drive over to my in laws.

By 1917 airships began to give way to long-range bombers and these Gothas and the later Giants were capable of flying higher and faster than the old gasbags. These aircraft could bomb with much more precision but this does not mean the Germans were able to single out targets of importance to blunt the British war effort. They might have bombed the great arsenal at Woolwich or the munitions works at Silvertown, Enfield or many others, but instead the bombers found other targets such as the Odhams print works or the unfortunate children of Upper North Street School in Poplar. But this tragedy was only one of a number that echoed down the decades through the wars in Spain and China and throughout the Second World War and since. It is fair to remember that it was believed that hitting soft targets was a way of causing dismay and unease that could weaken the resolve of an opponent. This was a design that would be well and truly disabused by the populaces of many major cities between 1939 and 1945. But it was early days when the Zeppelins and Gothas were airborne and strategists had much to learn.

The German bombers seemed to have free rein but it wasn’t all one-way traffic and a Gotha crash site about a twenty-minute drive from my home is where the first aeroplane to be shot down by another at night came crashing down to earth. That suitably armed Sopwith Camels could reach the desired height and deliver a knock out blow is a testament to how warfare drives innovation and invention.

You may live thousands of miles from the scenes of the events included in this book but if you are interested in the history of air warfare then there is much to take from the work of Alan Simpson. A glance through the sources listed at the back shows he has been no slouch in gathering useful information. The book pootles along in an easy to read and entertaining style and it didn’t take me long to rattle through it. I have no difficulty in recommending it to you.

Reviewed by Mark Barnes for War History Online

AIR RAIDS ON SOUTH-WEST ESSEX IN THE GREAT WAR

Looking for Zeppelins at Leyton

By Alan Simpson

Pen & Sword

ISBN: 978 1 47383 412 3