Great War books keep coming as the final months of the centenary period burns itself out. I’ve said, before, that the output has been just as mixed as the official events organised to commemorate those dreadful years but there is still time for decent books and this one from Sarah Reay fits the bill. In it she tells the story of her grandfather, the Weslyan minister Herbert Butler Cowl.

The Great War is rightly seen as a staging post in the loosening of the grip on society held by the established churches in the United Kingdom and elsewhere. Harsh experiences in the war and the rise of political ideas questioning the primacy of religion led quite a number of people to gradually turn their back on old ways. A century on and the authority of the church has diminished even further and whether that is a good thing or not isn’t something for this review but we have to be balanced and remember that religious faith was still very much a part of a great many lives during the period of the conflict. While I am not religious myself, I believe it is important that the dignity of a Christian burial is always applied when the remains of soldiers found out on the battlefields are properly laid to rest in a cemetery. In the vast majority of cases it is what they would have wanted and they should not be denied even a hundred years after their death.

The tenets of faith were applied by church and state to the armoury of countries seeking victory. Many Germans marched into battle with Gott Mit Uns inscribed on their belt buckles. All sides in the conflict were quite sure that God was with them and very few would question the fact in the way Bob Dylan would do in the 1960s. German barbarism, Hun frightfulness – there are many names for it – was met with righteous indignation in Britain and when the soldiers marched away to war there were padres with them to offer pastoral comfort and guidance. I have total admiration for the vast majority of those men. They quite often stepped into deadly situations and rarely flinched. A number of chaplains were decorated for bravery and perhaps the most remarkable of them was Theodore Bayley Hardy who had already earned the Distinguished Service Order and the Military Cross when he was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross in 1918 after being wounded retrieving injured soldiers from no mans land. This is all the more incredible when we learn that he was 54 years old at the time.

The bravery of men like Bayley Hardy is matched by the extraordinary work of others to make a difference, as any visitor to Talbot House – ‘Toc H’ – in Poperinghe, Belgium, will well know. It was there that the Reverend PTB ‘Tubby’ Clayton, another Military Cross recipient, set up his famous rest centre behind the lines with his colleague Neville Talbot. Another brave clergyman was Geoffrey Studdert Kennedy, who would also be awarded the Military Cross for bringing in wounded men from no mans land. He was a popular figure for handing out cigarettes to wounded soldiers, earning him the nickname Woodbine Willie after the brand of fags he usually distributed. It might not come a surprise that a man like Studdert Kennedy would go on to question his faith. Disillusioned by his experiences, he wrote a number of books taking a critical look at the role of religion in the war and was equally scathing of capitalism and the way people had profited from the conflict.

The subject of this book is a man who had no doubt about the importance of his faith and the good it could do. He was both devout and brave and possessed a sense of self-assurance that he was on the right path throughout the duration of his ministry. Modest and almost embarrassed by his fifteen minutes of fame, he had long since set his mind to doing God’s work and never lost sight of the teachings that made him the man he was. I am mindful that I am writing about Herbert Butler Cowl in the wake of the death of Billy Graham and the connections between the two men are palpable to me. Both were inspirational and utterly sincere in their beliefs. You cannot ask much more from a man of the cloth.

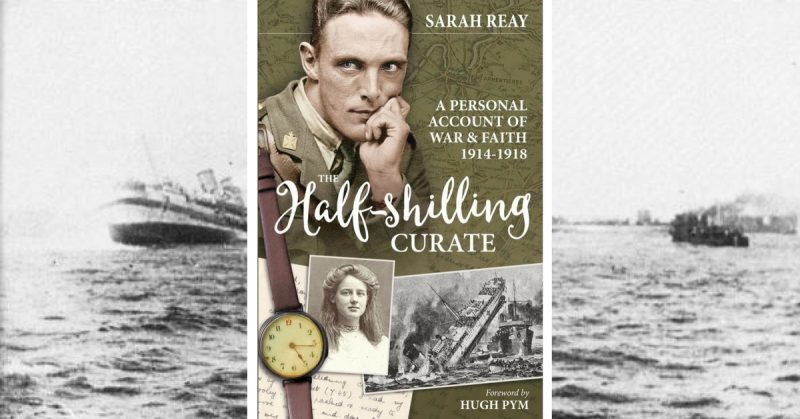

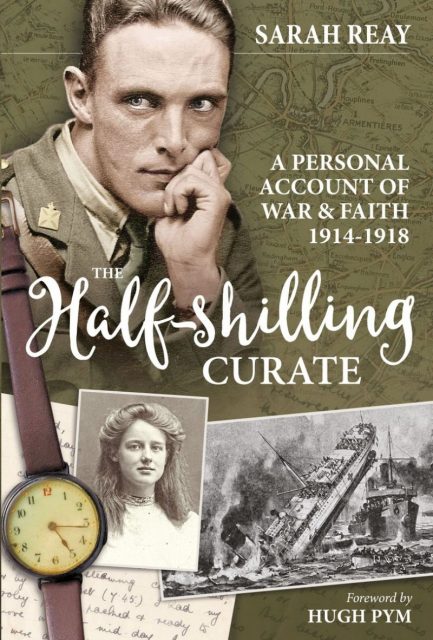

Herbert didn’t spend a long time exposed to the enemy, but he was seriously wounded and was lucky to survive. He set personal injury aside to help others when he could easily have put himself first. The notion of greater love applies to him in every sense. Having been wounded on the Western Front he endured the calamity of being on the hospital ship Anglia when she struck a mine in the English Channel. Herbert put others first, yet again, and it isn’t difficult to see why he, too, became a recipient of the Military Cross.

The war was just part of his life, but like so many others it tends to define him.

The author does much to explain that those four years were only a portion of a life given over to God and the love of his family. Faith comes in many forms.

This is a very nice book. The author tells Herbert’s story with a blend of simple clarity and enough detail to keep us engaged. She has a natural degree of affection and pride in her grandfather that sings through the pages and this serves to help the finished article along. Herbert is one of those footnotes of the war we find in the big tomes. The centenary has fleshed people like him out for us. Sometimes it works and other times it doesn’t. Happily this example is a success.

Reviewed by Mark Barnes for War History Online

THE HALF-SHILLING CURATE

A Personal Account of War and Faith 1914-1918

By Sarah Reay

Helion & Company

ISBN: 978 1 911096 46 7