The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) laid down many large ships during the Second World War. One was IJN Shinano, a Yamato-class ship that was converted into an aircraft carrier halfway through her construction, due to the heavy losses the Japanese fleet sustained during the Battle of Midway. Shinano has a unique story that ends with her being the largest warship ever sunk by a submarine.

Construction of the IJN Shinano

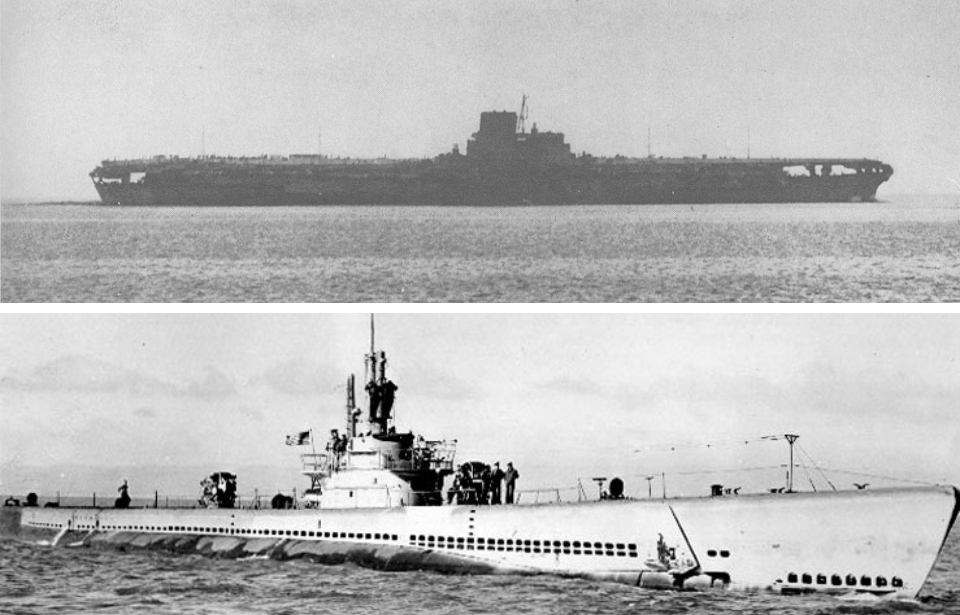

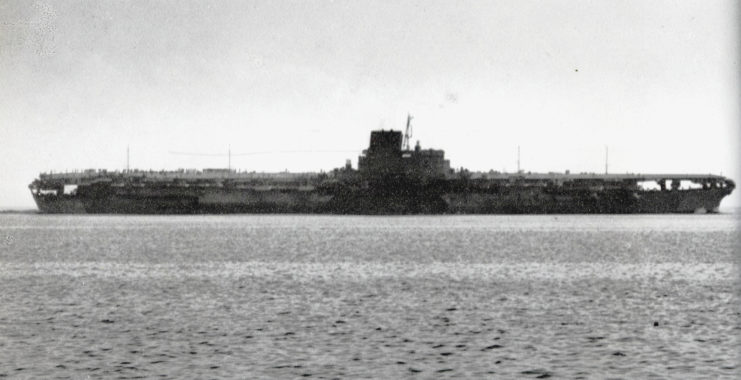

The IJN Shinano was laid down on May 4, 1940 at the Yokosuka Naval Arsenal as the final ship in her class. Construction proceeded well, until orders arrived in 1942 to convert the battleship into an aircraft carrier to replace those that had been lost to the Americans. Instead of a fleet carrier, she was designated as a 65,800-ton, heavily-armored support carrier for reserve aircraft and fuel.

Shinano‘s construction was kept a closely-guarded secret, blocked from view by a tall fence built around the compound. Even those who worked on the vessel were sworn to secrecy, under threat of execution. As such, Shinano was the only major warship of the 20th century to have no photographs taken during her construction. Even after she was built, she was only photographed twice: by a Boeing B-29 Superfortress on a reconnaissance mission and a civilian during sea trials.

Armor and armament

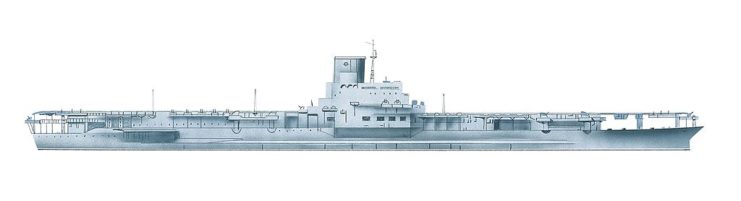

The IJN Shinano was a modification of the Yamato and Musashi design. She was intended to feature armor that was 10-20 mm thinner, as well as newer anti-aircraft guns. These features were further altered when she was turned into an aircraft carrier and, before long, was hardly recognizable as a Yamato-class ship, having lost most of her armor and large main guns.

Instead, Shinano featured the flat top of an aircraft carrier and an inline flight deck.

Shinano was 872 feet in length, with a beam of 119 feet and a draught of nearly 34 feet. Power came from 12 Kampon water boilers, which fed four geared steam turbines that drove an equal number of shafts through 150,000 shaft horsepower. This made her surface speed around 27-28 knots when conditions were ideal.

Shinano was designed to carry 47 different types of aircraft. As far as aircraft carriers went, she was considered defensively strong, equipped with eight twin five-inch dual-purpose guns, 35 triple one-inch anti-aircraft guns and twelve 28-barrel 4.7-inch anti-aircraft rocket launchers. At the waterline, Shinano’s armor was between 160 and 400 mm thick, and 75 mm at the flight deck.

Traveling toward certain destruction

Although the IJN Shinano wasn’t supposed to be commissioned until the beginning of 1945, her construction was sped up following the Battle of the Philippine Sea, where the Japanese lost two fleet carriers, one light carrier and two oilers. Multiple smaller ships had also been damaged during the engagement.

The drive to ramp up the vessel’s completion meant poor workmanship was done on the later elements. Nonetheless, Shinano was launched on October 8, 1944 and commissioned on November 19 of that year.

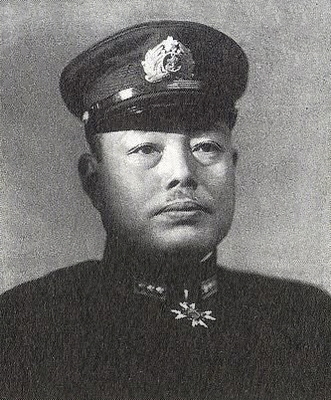

At this point, Shinano was intended to travel from her shipyard to Kure Naval Base, to be fitted with armaments and receive aircraft, under the command of Capt. Toshio Abe. Although he was under pressure from his superiors to leave as soon as possible, Abe requested his departure be delayed, as the bailing pumps and fire mains had not yet been completed. His request was denied. He was also forced to make his voyage at nighttime, despite his preference to set off during the day.

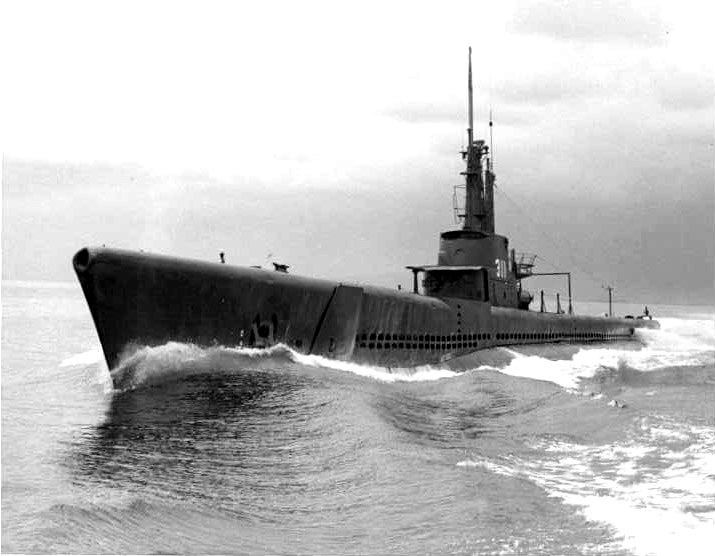

Shinano departed for Kure at 6:00 PM on November 28, 1944, accompanied by Isokaze, Yukikaze and Hamakaze. After traveling for some time, the ships detected the radar of an American submarine in the area and began sailing in zig-zag movements to try and evade the submersible. Unbeknownst to her crew, this actually put Shinano right in the path of the USS Archerfish (SS-311).

Sinking of the IJN Shinano

The USS Archerfish, under the command of Cmdr. Joseph Enright, had clocked the IJN Shinano two hours before the submarine was noticed by the Japanese aircraft carrier. Abe, believing they’d encountered an American wolfpack, ordered his ships to turn away from Archerfish, in an attempt to outrun the submersible. This would have worked, as Shinano was the faster out of the two, but she was forced to reduce her speed to prevent damage to the ship.

By 2:56 AM on November 29, Abe had changed direction to move toward the submarine, only to turn southwest, exposing the entire side of the ship to Archerfish. At 3:15 AM, Enright made the call to fire six torpedoes at their target, ensuring the first two hit before diving to a depth of 400 feet to wait it out.

Four of the torpedoes hit Shinano, which was enough to sink her. Enright and his crew didn’t know what ship they’d sunk until the Second World War was over, nor that it took over seven hours for the aircraft carrier to go down.

Hindsight is 20/20

Initially, those aboard the IJN Shinano didn’t think the damage caused by the torpedo strikes was severe, and therefore made little effort to save the ship. Abe, in particular, ordered her to continue at maximum speed, which only flooded the aircraft carrier quicker. By the time they realized there was a serious problem, it was too late. She was too heavy to be towed by the escort ships, too flooded to be bailed out and too far gone for the majority of her crew to escape.

Of her 2,400-man crew, 1,435 went down with the ship, including Abe and both navigators.

Those who survived were sent to Mitsukejima until January of the following year, so news of Shinano’s sinking didn’t spread. After the war ended, the US Navy analyzed the aircraft carrier, as well as the other Yamato-class ships, and determined they had severe design flaws that made certain joints vulnerable to leakage. They believed the USS Archerfish’s torpedoes happened to hit these joints, which were prone to rupturing, contributing to Shinano‘s demise.

More from us: Battleship Row: The Nine American Vessels Targeted During the Attack on Pearl Harbor

As for Enright, US Naval Intelligence didn’t believe him when he said he’d sunk a Japanese carrier, as they thought all had been accounted for. After the war, this was corrected, and the commander was awarded the Navy Cross for his victory.