Phantom was the prototype of a self-propelled concrete tank vessel, designed by Vladimir Yourkevich and F.B. Woodworth. A unique concept developed to potentially protect against the enemy U-boat threat at sea, there was hope it would enter into full-scale production. The following is the story behind this “Concrete Curiosity.”

Vladimir Yourkevitch and F.B. Woodworth

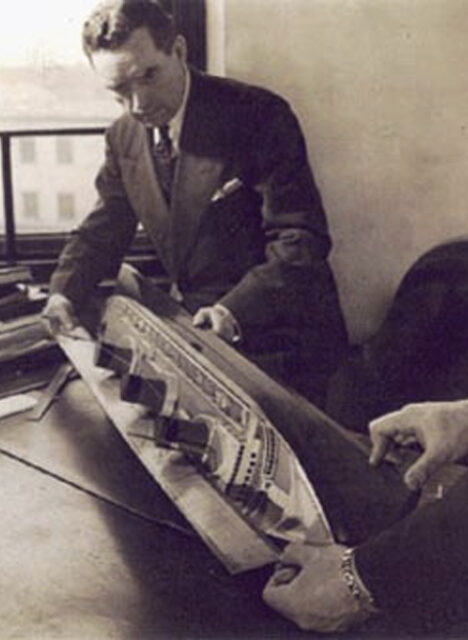

Russian-born Vladimir Yourkevitch was best known as the designer of the French luxury liner, SS Normandie. He’d designed submarines for the Imperial Russian Navy during the First World War, before traveling to the United States in 1937. There, he chartered Yourkevitch Ship Designs, Inc. with a share capital of $90,000 to obtain and develop patents.

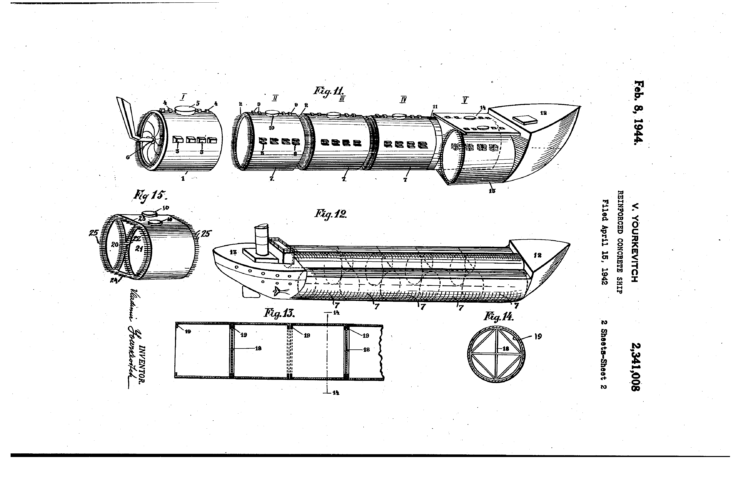

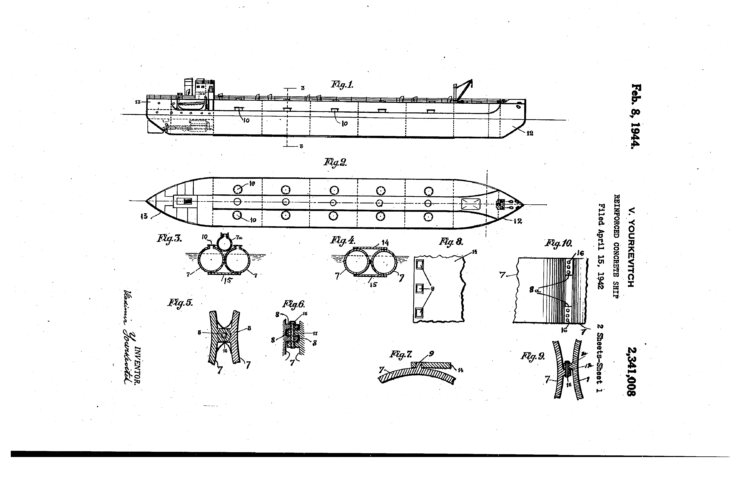

A patent for the design of this reinforced concrete ship was applied for on April 15, 1942, and granted on February 8, 1944.

F.B. Woodworth, formerly of Bell Laboratories, was prominent in the development of the ship-to-shore radiotelephone. He was an executive of Maris Transportation System and the Radio Controls Corporation who reportedly developed designs along with Yourkevitch. Maris Transportation System was also contracted to build two Liberty steel tankers.

Design, building and launch of Phantom

Phantom was launched on October 19, 1942, and christened by J. Stanley Reeve, Jr., the wife of the president of Tropical Marine Ways, which built the vessel. She was 91 feet, six inches in length, with a beam of 14 feet and a depth of six feet, one inch.

The vessel weighed 78 tons, 68 of which were concrete, while 10 were steel, representing the proportional savings of steel for a ship of her size. Her cargo capacity was 100 tons (approximately 54,000 gallons), hence her displacement of 178 tons. She was powered by a six-cylinder, 80-horsepower diesel engine built by Cummins Engine Co. of Columbus, Indiana.

Phantom was the prototype of a planned ocean-going tanker that would be propelled by a 1,000-horsepower diesel engine, which would provide a speed of 10 knots. It was estimated that the cost of the full-scale model would be $120,000, about half that of the average steel and wood boat.

Design-wise, there were marked similarities to the self-propelled “Whaleback Tankers” built by McDonald Engineering at Aransas Pass, Texas to transport oil. Named Durham and Darlington, they were radical in design as, rather than being constructed with a monolithic design, they were made up of nine separate sections, each cast separately and joined together on a long launching way. Both tankers proved to be impractical, underpowered and unstable at sea – a failed World War I-era experiment.

A possible solution to the U-boat threat

On December 18, 1942, newspapers reported, “Phantom Convoys of Concrete Freighters Seen as Answer to Submarine Menace.” It was a new and revolutionary idea whereby convoys of crewless concrete tankers could be operated automatically and remotely from a master escorting vessel.

Also announced was that the building of the “model” was seen as a possible solution to many wartime shipping problems, not the least German U-boats. They were called “phantoms” because they’d be virtually invisible in the water, their center of gravity so low that their decks were almost flush with the ocean surface. All openings, ports and hatches were sealed – only the air intakes for the engines and ventilation of the holds were above water.

As there was no crew and they were radio-controlled from an escort ship, there would be no superstructures, such as a bridge. If one pictures a convoy of almost submerged vessels, similar to cigar tubes, that’s close enough! The concept was for a convoy of 10 such vessels for each escort ship, thereby being able to transport a total of 20,000 tons of fuel at once.

Important to the design was that the full-scale version would have watertight compartments along the length and breadth of the vessels. In the event one or more were to be hit by enemy torpedoes, there were ballast tanks that could be flooded to bring the ships back to an even keel.

Technological advancement

In terms of technological advancement, F.B. Woodworth’s contribution was that he designed a secret system of ultrashort-wave and code-signal devices that enabled the escorting vessel to control the “phantoms.” If the control vessel was sunk, they would proceed for two hours on the same course, at which point the mechanisms aboard would halt them and send out distress signals giving their approximate position.

It’s not quite Tesla technology, but it was 80 years ago!

Phantom was a ‘proof of concept’

Phantom was a prototype, a “proof of concept” as it were, that was built and funded privately, with the aim to have it tested by the US Maritime Commission and American Bureau of Shipping. In this respect, the vessel is reported to have “sailed” 1,404.4 miles within 165 hours through the inland waterways from Riviera, Florida to Washington, DC for testing. For this, a makeshift bridge was constructed for the operating crew.

If successful and adopted, the potential returns for the investors would have been huge. Some $166,999,276 was reportedly spent on the Maritime Commission concrete shipbuilding program, which was initially conceived to solve the problem of transporting oil from the Gulf of Mexico to the Eastern Seaboard.

By May 1942, the Maritime Commission had contracted for 67 ocean-going concrete oil barges to be built by three constructors in Savannah, Georgia; Houston, Texas; and National City, California. Of this, just 33 were actually built.

Phantom‘s trials and tribulations

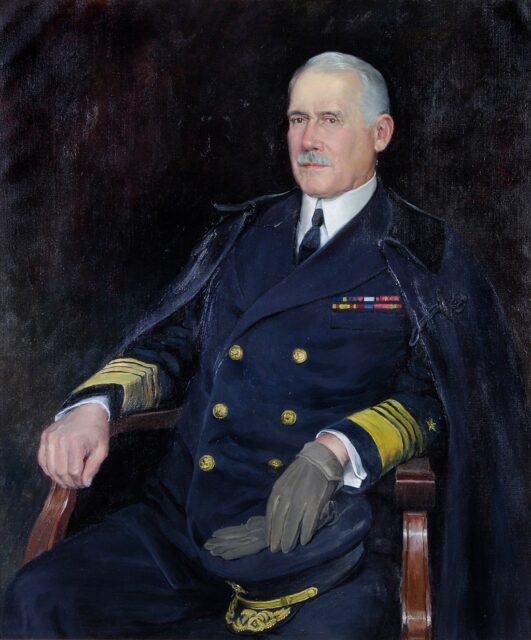

On December 28, 1942, Newsweek reported, “The Maritime Commission had not yet reached a decision on the plan and that Admiral Emory S. Land, Commission chairman, said only that it was under consideration.”

Adm. William V. Pratt wrote a critique of the concept, again published in Newsweek, that argued, among other things, that “there was never a craft sailing blue water that did not require constant upkeep to function efficiently” and that, as the convoy would be unarmed, the need for escorts would increase, not diminish.

Self-evidently, the idea didn’t float with the Maritime Commission and Phantom wasn’t included in their program of concrete shipbuilding that ultimately constructed 104 concrete vessels, many of which served in the Pacific Theater during the Second World War – many still exist today.

Popular Science in March 1943 produced an article explaining Phantom, which was photographed being trialed at the Capitol Yacht Basin in Washington.

Phantom appeared in the list of Merchant Vessels of the United States in 1945, and, in ’46, first appeared on the Lloyd’s Register of Shipping, registered for service in New York Harbour & Long Island Sound by Maris Transportation Systems and utilized for carrying water. By 1948, she was no longer listed. It would be reasonable to assume she was scrapped or scuttled – she became a phantom!

More from us: The Tragic Last Stand of the HMS Hood Against Germany’s Prized Battleship Bismarck

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no full-scale versions of Phantom were ever constructed. The vessel will remain forever in the annals of history as one of many “Concrete Curiosities.”

Richard Lewis and Erlend Bonderud are renowned concrete ship researchers, authors and speakers.

Through their collaboration, they’ve researched and chronicled the “life and times” of over 1,600 concrete vessels built around the world, from 1848 to date. They are progressively sharing this research on their website through a series of blogs. Every concrete vessel built in the United States during both World Wars has been described in accurate detail on their website, which is linked above.