Have you ever wondered why there’s so little footage from the D-Day landings on June 6, 1944? It’s easy to assume that filming was too risky or simply not a priority, but that’s not the case. In fact, the Allies made a concerted effort to document the historic event. So, where did all that footage go? The answer lies at the bottom of the English Channel, and it’s all because of one man: Maj. W.A. Ullman.

Documenting D-Day

D-Day stands apart as a key military event in World War II – and in the broader scope of history. Its importance was acknowledged even at the time, prompting a deliberate effort to document it in detail.

Filmmakers organized teams to join the troops landing on the beaches of Normandy, capturing as much as possible despite the many risks involved. Photographers were also deployed, and cameras were installed on hundreds of the supporting vessels, as well as on many of the landing craft ferrying soldiers to the shore.

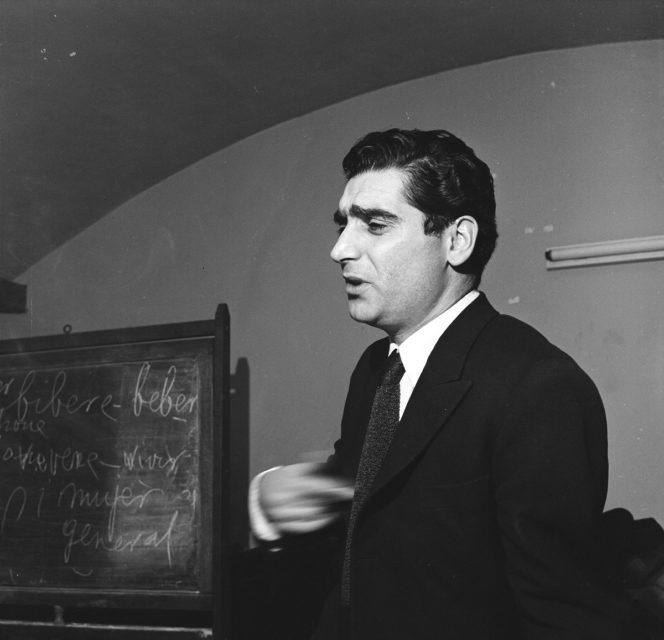

John Ford was tasked with filming the action on Omaha Beach

One of the men involved was American film director John Ford, who served as the head of the Field Photographic Unit for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) and had made numerous high-profile movies of World War II. He’d recorded the Battle of Midway as it happened, being wounded in the arm while doing so. Much of the work done by Ford and other directors like him was to support the war effort and was, essentially, propaganda.

On D-Day, Ford was there to film as the ferocious battle unfolded. He was to document the most deadly location of the landings: Omaha Beach.

Earning the Distinguished Service Medal for his efforts

John Ford was given a crew of US Coast Guard cameramen to manage during the landings. They arrived off the coast of Omaha Beach on June 6, 1944, and witnessed the first wave launch their assault. He and his men then landed on the beach themselves sometime later and began filming. His efforts earned him the Distinguished Service Medal.

Unfortunately, almost none of the footage Ford and his crew recorded would ever be seen.

Lost footage in the English Channel

Tragically, much of the footage John Ford and his men risked their lives to get was lost to the sea.

A large amount of film was placed into a duffel bag to be sent back to Britain. However, the junior officer carrying it, Maj. W.A. Ullman, accidentally dropped it into the English Channel. Some of the most detailed and extensive footage of the landings was lost forever.

Meanwhile, the piece of film that wasn’t placed in the cursed duffel bag was simply destroyed in the midst of the chaos. Water seeped into the equipment and many cameras mounted on ships and landing craft didn’t survive. As a result, there’s now very little footage that exists today showing the first few hours of the landings on Omaha Beach.

Some footage did survive

However, a surprisingly large amount of footage did survive and was developed, but it’s believed Allied governments withheld it because of the horrors it contained. John Ford later said in 1964 that the US government was “afraid to show so many American casualties on the screen.”

Some of this footage was discovered in the 1990s, but exactly what it shows is unknown.

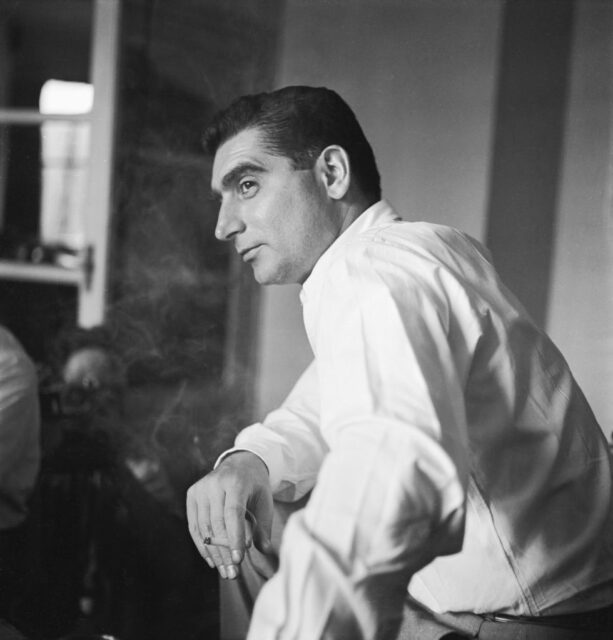

Robert Capa encountered a similar situation

A similar situation happened to Robert Capa, a civilian war photographer hired to photograph the D-Day landings.

Capa arrived on Omaha Beach alongside the 16th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division (the “Big Red One“) just an hour and a half after the invasion had begun and managed to take photos of the action around him. Capa claimed to have taken 106 images, but only 11 were usable, becoming known as the “Magnificent Eleven.”

These photos were the only ones that showed Omaha Beach at this stage of the landings. The rest of the extremely historically valuable images were said to have been destroyed in a processing incident once they’d been sent back to London.

Coming under fire in recent years

This claim has come under fire in recent years, with some suggesting that only 11 were ever taken. Regardless, the photos Robert Capa captured have become the defining images of the fight that took place at Omaha Beach and even D-Day as a whole. In fact, they were used by Steven Spielberg as inspiration during the filming of Saving Private Ryan (1998).

More from us: Germany Hoped to Weaponize the Occult to Win the Second World War

Want to become a trivia master? Sign up for our War History Fact of the Day newsletter!

With the significance of just 11 photos of the action that took place at Omaha Beach, one can only imagine the value of the entire reels of film that were lost.