A little after 1:20 AM on March 28, 1942, searchlights on both sides of the Loire Estuary flooded the waterway to reveal a convoy. Twelve motor launch boats, a motor gunboat, a motor torpedo boat and a destroyer had somehow managed to slip over the sandbanks flying German colors and signal lighting friendly code.

That little delay didn’t last long before the Germans guarding the estuary, the vital Saint Nazaire harbor, and Normandie dry dock opened up all their guns on the approaching British sailors and commandos. At 1:28 AM, Lieutenant Commander Stephen Halden Beattie ordered the Royal Navy’s White Ensign raised on the destroyer HMS Campbeltown, as she sailed for her target: the gates of the dry dock.

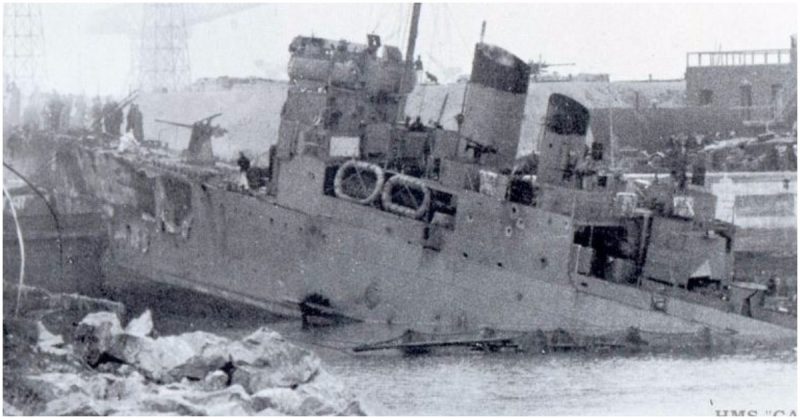

A few minutes of exchanged gunfire with the German shore positions later, Campbeltown drove her weight into the gates, pushing 33 feet into the dock. A commando group divided into assault, demolition, and protection teams disembarked, cleared the area, and blew up the dock’s water pump and gate machinery at a great cost of life.

But their comrades in the two columns of motor launch boats that had come in on the port and starboard sides of the Campbeltown were dying even faster. Most of those boats were burning or exploded on the push down the Estuary under fire. Some managed to put their troops ashore to little better life-expectancy.

All these men knew the importance of the mission and 169 of the 346 Royal Navy sailors and 264 commandos that participated perished with a further 215 taken as prisoners of war. They did, however, destroy the most important harbour in German-occupied France, dealing a monumental blow to Germany and especially the Kriegsmarine.

The naval facilities at Saint Nazaire included a port outside the gates to two basins, submarine pens, and the only dry dock on the Atlantic side of the British naval blockade that could hold ships like the Tirpitz, sister ship of the Bismark, which were priceless to Hitler’s war effort.

Trying to limit civilian casualties, the British ruled out an air raid to destroy the naval compound. The Royal Navy didn’t believe they could get their ships within range to bombard it without being detected. Combined Operations Headquarters took the job and with a massive joint effort between various branches of the services, managed to rig together Operation Chariot, The Greatest Raid of All Time (the name of the BBC documentary narrated by Jeremy Clarkson).

Commandos and men from the Royal Navy and Royal Engineers comprised the main force of the raid. The Naval Intelligence Division, Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), the War Office’s Military Intelligence, Royal Navy’s Operational Intelligence, and the Air Ministry’s Air Intelligence all contributed to the operation. Technical journals from before the war detailing aspects of Saint Nazaire were studied in depth.

It was decided that the Campbeltown would be used to ram to dry dock and transport one group of commandos. Two more commando groups were to ride on the two columns of motor launch boats to disembark at the old gates to the Bassin de St. Nazaire (right next to the dry dock gates.

Northeast of the port which held the new gates, and across the basin from the submarine pens) and at the Old Mole jetty. All the groups had separate teams for assault, demolition, and protection and objectives were set to cripple the harbor and German naval operations.

Furthermore, Campbeltown‘s bow was filled with 4.5 tons of high explosives hidden in concrete and timed to blow hours after the raid was over.

Only a few of the motor launch boats managed to reach the old gates and put men ashore after the Campbeltown rammed the dock and her group of commandos stormed the facilities. Some of the Campbeltown commandos, including those wounded like Beattie, managed to escape off the back end of the destroyer, when one motor launch boat, ML 177, parked behind with a full-scale battle raging around them between the other boats and German guns. ML 177 was later sunk while trying to escape.

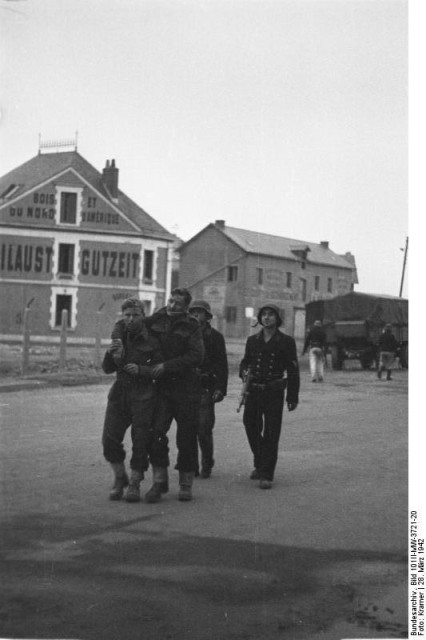

The Old Mole and old gates were not secured and with most of the other boats destroyed or being destroyed, the 100 or so commandos alive on land, lead by Lieutenant Colonel Charles Newman, had to escape on foot.

According to Combined Operations: The Official Story of the Commandos, by Louis Mountbatten, Newman ordered those men to do their best to return to England, to not surrender until out of ammo, and to not surrender at all, if they could help it. They fought their way through the town until they were surrounded and had expended all their ammo, before being captured by German soldiers.

Many more sailors and commandos were captured by the Germans after their boats sunk or exploded in the Estuary. The motor gunboat and four motor launch boats survived the raid and along with 228 men, made it safely back to England. Of the commandos who fought through Saint Nazaire, five managed to evade capture and escape to Spain with the help of the French and eventually to Gibraltar and back to England.

Eighty-nine decorations were awarded for Operation Chariot, many posthumously, including five Victoria Crosses and four Croix de Guerre (Britain and France’s highest military honors).

From a series of interviews with people (fighters and civilians) to do with World War II gathered from the Imperial War Museum by Max Arthur and called Forgotten Voices of the Second World War. Comes the story of Beattie being interrogated by a German officer. The officer taunted Beattie, claiming the damaged inflicted by the raid would be easy to repair, implying the great loss of life to have been a waste.

This was at noon on the 28th, just hours after the raid. And as the officer made his poorly-timed remarks, the charges in the Campbeltown detonated. Some 360 Germans were killed in the explosion and the damage to the dock took until several years after the end of the war to be repaired. Beattie smiled.

“We’re not quite as foolish as you think!”.

By Colin Fraser for War History Online