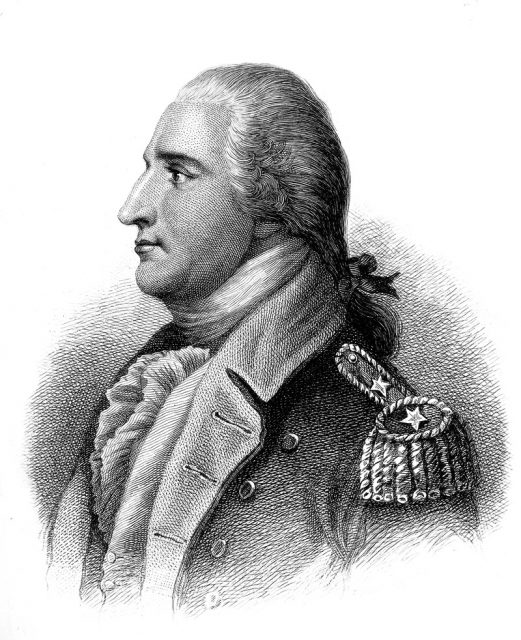

In history, Benedict Arnold is a controversial American figure, and is popularly remembered for his treachery, both to his nation and–more personally–to George Washington. However, he also performed quite a number of heroics in his day, claiming a few desperately needed wins for the Continental Army, and was considered by many a good man before a sudden twist of fate.

Benedict Arnold was born in the colony of Connecticut in 1741, the second of six children, four of whom were lost to an outbreak of yellow fever. Arnold was left behind with a broken father who was given to alcoholism. When Arnold was fourteen, his family had become so impoverished that his education was brought to an abrupt halt, and he took up an apprenticeship with his cousins for seven years.

He learned to be responsible for his only surviving sister and continued to care for her long after the demise of his mother in 1759 and his father in 1761. Arnold worked hard, and began his trade in books and medicines in 1763.

His first encounter with military operations was during the French and Indian War, during which he joined the Connecticut militia in 1757 at the age of 16. He joined in the march to Albany, New York and Lake George after the French besieged Fort William Henry in northeastern New York. In 1775, during the American Revolutionary War, he rose to the position of captain, and participated with the Continental army in the siege of Boston that lasted about eleven months.

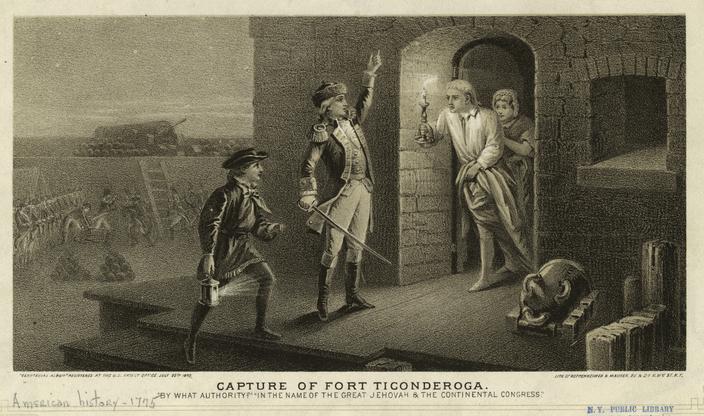

He discovered that Fort Ticonderoga was poorly guarded and that the supplies it contained could meet the Continental army’s needs of ammunition and cannons. Capturing the fort would also mean gaining control of some major trade routes to Canada. Accordingly, he obtained the necessary permissions and teamed up with Ethan Allen and his Green Mountain Boys to successfully seize the fort from the British.

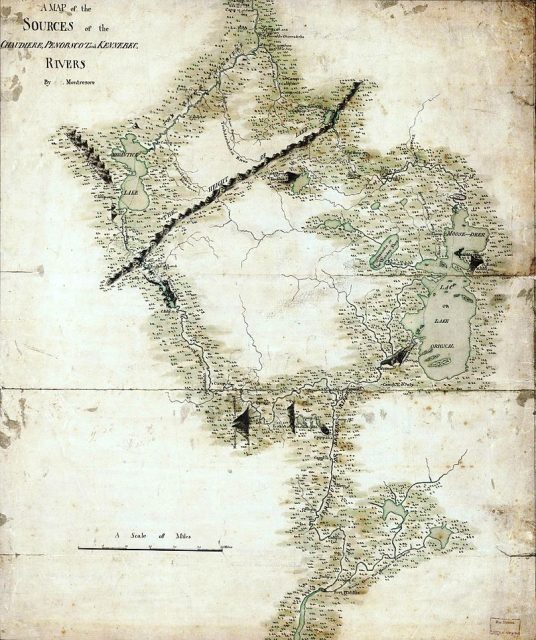

Afterward, he again urged the Continental Congress to authorize his plan to invade Quebec. They eventually did–but passed him over for commanding the expedition, instead appointing General Richard Montgomery to that position, while assigning Arnold to lead a smaller group of soldiers through the nearly impassable wilderness of Maine into Quebec. The Continental Army lost this battle to British defenders.

The army’s military force was severely weakened as a result of an outbreak of yellow fever, Montgomery was killed, and Arnold sustained major injuries to his left leg.

For his efforts to seize Quebec, Arnold was promoted to brigadier general, and traveled to Montreal to serve as the military commander of the city. He tried to halt the British military advance toward Valcour Island but was unsuccessful, and only managed to hold on to Fort Ticonderoga until 1777.

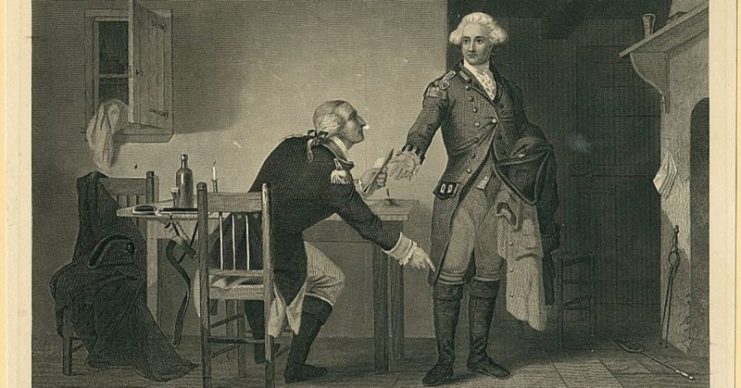

By this time he had risen in ranks and gained the favor of notable people like George Washington and Horatio Gates. However, Arnold had a reputation of mendacity and was disliked by some military officers and politicians who thought him to be overly ambitious.

He was passed up for promotion to major general on multiple occasions by Congress. He wrote to Congress to no avail and tried to resign, but Washington would not accept his resignation.

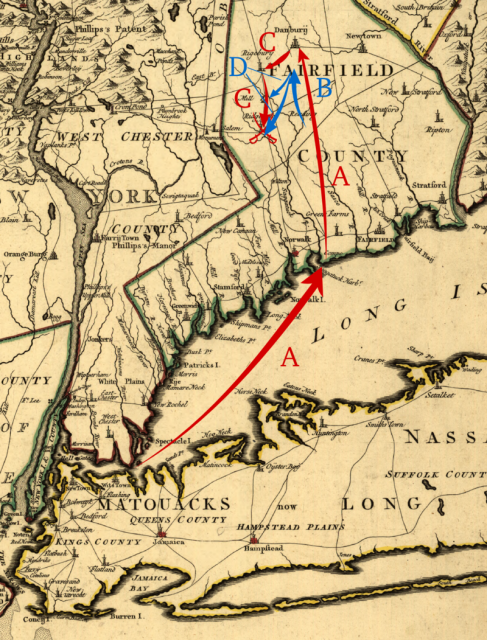

Arnold tried to stop the British return to the coast with a small militia group, and was again severely injured in his left leg in the battle of Ridgefield. After this incident he was promoted to major general, but his command was not restored, and he was still lower in rank compared to his contemporaries.

In the battle of Saratoga, Arnold displayed unusual bravery and ingenuity in spite of further injury to his left leg, earning his much desired restoration of command from Congress–but at this point he considered the promotion to be mere sympathy for his wounds, rather than recognition of his skill.

Washington appointed Arnold military commander of Philadelphia in 1778, where he lived affluently to the point of extravagancy, borrowing large sums to afford his lavish lifestyle. He was involved in some illegitimate business arrangements which included using his command for personal benefit, much to the uproar of some politicians in Philadelphia, but most charges brought against him were eventually dropped for insufficient or circumstantial evidence.

In Philadelphia, Arnold met and then married Miss Peggy Shippen. Peggy was a Loyalist sympathizer who had previously been courted by the British spy Major John André. Arnold’s marriage to Peggy fostered relations with André, who began to manipulate Arnold for the British High Command.

Arnold had lost his business in Connecticut to the war, spent many years in service to his country, lost most of the function in his left leg to battle wounds, been passed up by Congress for promotion on multiple occasions, been court martialled by civil authorities in Philadelphia for misappropriation of funds, lost faith in his country and fellow countrymen, and was up to his neck in debts to both private citizens and Congress.

All of these factors softened Arnold up to André’s enticing offers to give up classified military intelligence in exchange for safe escape and asylum in the eventuality of a British invasion.

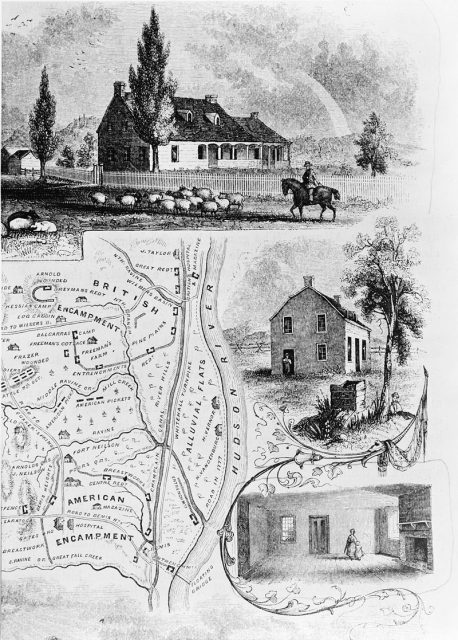

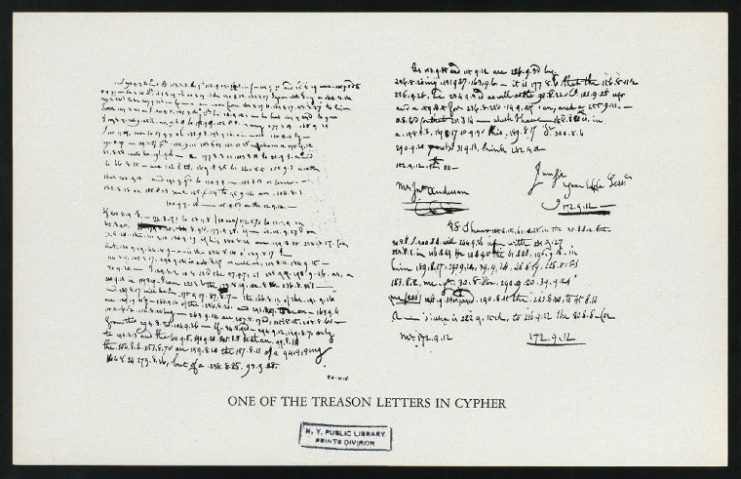

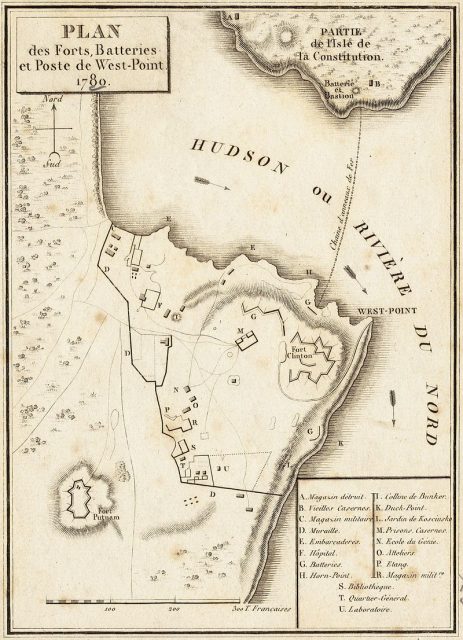

Arnold obtained command of West Point on 3 August 1780. He began sending encoded letters through Peggy to Major André, with accurate and detailed information that helped André gain victory in the siege of Charleston. This piqued the interest of General Henry Clinton, who wanted to capture West Point to prevent its occupation by the American Continental Army.

Arnold promised to relinquish command of West Point in exchange for £20,000, with £1,000 down payment as a show of good faith. He hoped to use this down payment to offset his debt to Congress. General Clinton agreed to these terms, ushering in a series of coded letter transmissions between Arnold and Clinton through Joseph Stansbury, a resident in Philadelphia who opposed armed resistance.

Arnold disclosed pertinent information regarding the size, security, and positioning of the army at West Point. He also tried to weaken the military defenses by redistributing soldiers and delaying requests for much needed supplies and ammunition.

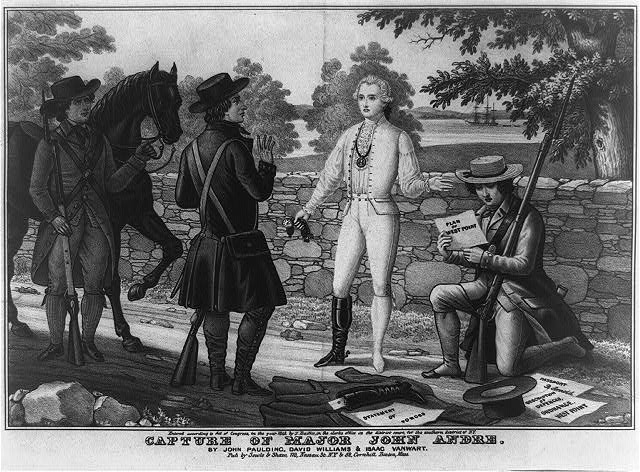

He met with André on September 21, and as they discussed plans to capture West Point, Arnold drew out detailed plans of passages into and out of West Point, including the security details at various checkpoints.

Unfortunately for Arnold, André was captured two days later and the plans were found on him. Arnold’s role in the plot to give up command of West Point to the British came to light after General Washington examined the plans. An issue for Arnold’s arrest was ordered, but he fled to New York, where he wrote a letter to Washington admitting his crime, but insisted that his wife Peggy was innocent and asked that she not be harmed.

Washington agreed to this and an exchange of André for Arnold was proposed, but Clinton refused to make the trade. André was hanged on October 2 after a military tribunal. Washington sent soldiers to capture Arnold in New York, but the attempt failed and Arnold fled to Virginia. There he wrote an open letter to the American people, titled “To the inhabitants of America” and justifying his actions, that was published in October 1780.

Now in the service of the British military, he received only a quarter of the previously agreed-upon amount for plotting to help the British capture West Point, because although he provided the information, the plot failed.

He went on several raids under the command of General Clinton in Virginia, New London, Fort Griswold and even his beloved home colony of Connecticut, all the while wreaking havoc and damages estimated at up to $500,000. However, his recklessness resulted in many casualties, much to Clinton’s displeasure.

Before the British surrendered, Arnold obtained permission to go to England, where was well received by King George III but was disliked by many in military and political circles. He made some attempts to rise in power, but was unsuccessful as he was considered by most to be untrustworthy.

He eventually relocated to Upper Canada where he lived out the rest of his civilian life. He suffered from gout and his health continued to decline until, after a prolonged episode of delirium, he died on June 14, 1801 at the age of sixty.