Within the context of the use of small arms in linear warfare, the American Revolutionary War was a conflict dominated by the musket. Smoothbore muzzleloaders were the predominate long guns of the period.

The British employed the Long Land Pattern “Brown Bess,” one of the most prolific muskets of the eighteenth-century. The Continental Army, meanwhile, relied upon French firepower in the form of the Charleville flintlock—although many colonists managed to get their hands on the Brown Bess as well.

At best, the above observations are generalizations that, like other facets of the past, overshadow some frequently overlooked exceptions to the record. One of the most interesting of these exclusions was the Ferguson Rifle, a weapon produced in response to the American Long Rifle (another deadly anomaly that I plan to cover in a future article).

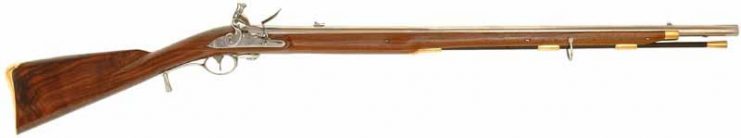

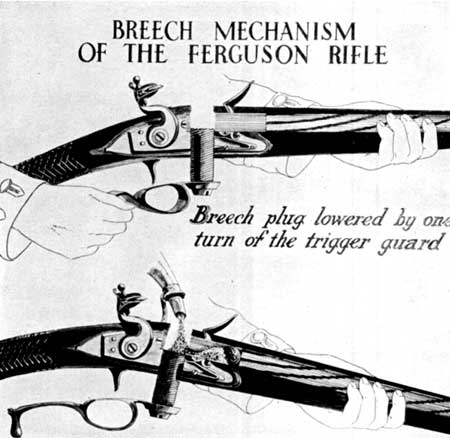

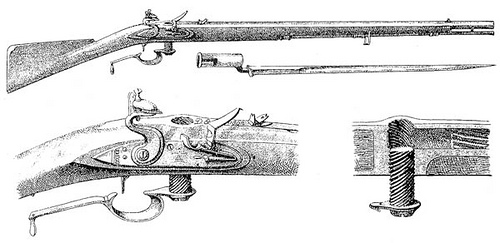

A breech-loading flintlock, the Ferguson was one of the first such firearms employed by regular forces in battle. The rifle fired standard ammunition of the period (a .615” British carbine ball) but was based upon an innovative multiple thread, screw-type action pioneered in the 1720s by the French handgun inventor, Isaac de la Chaumette.

By all accounts, the Ferguson Rifle was a weapon that outperformed conventional long guns of the period in nearly every regard. In the hands of a trained soldier, it fired faster, farther, and more accurately than any musket of the eighteenth-century.

This of course begs two questions. First, what happened to the Ferguson Rifle? Second, why didn’t the Crown use the weapon to quickly crush Patriot resistance, bringing a swift end to the war? The answers, in both cases, are best explained by starting at the beginning.

In 1775, Captain Patrick Ferguson was a Scottish officer in the British Army. No stranger to conflict, Ferguson entered the military in his teens and saw some of his first action in the Holy Roman Empire, fighting with the Royal Scots Greys during the Seven Years’ War.

Shortly after returning home, Ferguson purchased a posting in the 70th Regiment of Foot under the command of his cousin, Alexander Johnstone. He served a brief stint in the West Indies, returning home in 1772 with an undiagnosed leg ailment. It was during this period—between training in Great Britain and departing for North America—that Ferguson set his design in motion.

As the story goes, Ferguson managed to produce several protype rifles that he placed in the hands of ten trained marksmen who, along with Ferguson, demonstrated their use in front of the British War Office and Board of Ordnance. Despite being forced to perform in driving rain and gusty winds, Ferguson’s cadre of sharpshooters won the immediate admiration of the Board.

Among other accomplishments, the test demonstrated that the rifle could “put 15 balls on a target at 200 yards in 5 minutes,” and, “after pouring a bottle of water into the barrel… fired as well as ever.” Ferguson’s design was a vast improvement over the Brown Bess, which was only reliably accurate up to about 50 yards.

The Board issued requisitions for the first 300 rifles during the summer of 1776 and Ferguson was officially issued a patent later the following December. Unfortunately, the Scot had little time to celebrate. Difficult and expensive to produce, approximately 45,000-55,000 Fergusons were needed to completely outfit the British Army at the outset of the war.

Firearms manufactures were only able to produce the weapons at a rate of about 1,000 per year, however, which meant they would ultimately see limited use in a conflict originally projected to last a few short years.

Officials achieved a compromise in 1777 when King George ordered the “forming of a Company of 100 Men” that would be armed with the new rifles, under Ferguson’s command. After arriving in New York, General William Howe augmented Ferguson’s unit by directing the formation of “a Corps of Rifle Men under the Temporary Command of Cn. Ferguson 70th Regt. compos’d of Recruits rais’d for Difft: Regts. serving in N: America…” Logistical pitfalls and supply shortages prevented the complete outfitting of Ferguson’s sharpshooters with his new rifle, which diminished its reputation in battle (only two-thirds of his men were armed with Fergusons).

Ferguson’s band of light sharpshooters saw action at the Battle of Brandywine Creek (September 1777), where British and Hessian forces decisively defeated the Continental Army near present-day Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania.

In addition to chalking up an impressive number of enemy casualties, Brandywine was the engagement where Ferguson supposedly and unknowingly had General George Washington in his aim but fatefully decided not to take the shot. While historians debate the merit of this claim, its likely that Ferguson could have ended the nascent uprising with the single pull of a trigger.

Ferguson was wounded at the Battle of Brandywine and didn’t return to full duty until the following year. Consequently, his corps of sharpshooters fell apart and was disbanded in his absence. Most of the Ferguson rifles were subsequently boxed-up in and placed in storage.

Claims that the Ferguson Rifle later saw action during the Southern Campaign of the war are unsubstantiated, although Ferguson himself was killed in action at the Battle of Kings Mountain (South Carolina) on October 7, 1780. Contrary to some popular reports, Ferguson was not armed with his breech-loading rifle at his final battle.

Ferguson’s death paralleled the fate of his rifle that, by the time of his demise, was mostly collecting dust in a New York warehouse. In addition to the production issues that prevented the widespread issuing of the firearm, the Ferguson rifle reportedly suffered from a fragile stock that sometimes cracked in the heat of combat.

These issues, coupled with the grim reality that Great Britain was losing control of her colonies, condemned the Ferguson Rifle to the dust bin of history. Amazingly, it took another 80 years for the next breech-loader, the Sharps Model 1863 Carbine, to appear in mass numbers on the battlefield. If anything, that fact alone should validate the vision and ingenuity of Patrick Ferguson.