The siege of Yorktown was considered to be the last major land battle of the American Revolutionary War. It was fought from 28 Sept – 19 Oct 1781. The battle was fought by Americans and French against the British and their German mercenaries. General Washington and Lieutenant-General de Rochambeau commanded the American and French troops respectively. On the other end, the British and German troops were commanded by Major-General Lord Cornwallis.

The summer into the fall of 1781 heralded the last days of the Revolutionary War, the British Southern campaign plan was in shreds after the successive victories and near victories by American forces in the South. They were now restricted to coastal towns.

Meanwhile, the French reinforcements which were promised to the Americans had finally arrived in Rhode Island, following the initial plan which slated the French to combine with the American forces and retake New York.

The Americans and their allies also enjoyed a unique advantage, for the first time in the war, French Naval forces in the Western Atlantic were superior to the British forces.

France had been engaged in a decade-long effort to grow its Navy. Their efforts reached fruition in 1781, while the British Navy, which remained as formidable as ever was stretched around the world, in a global fight for naval superiority.

On July 8, 1781, the French army completed its 18 days march from Rhode Island, arriving near White Plains, New York to join the US Army there. The two armies then headed south toward New York City.

Upon their arrival, the combined forces of America and France found the defenses of New York to be formidable. They, however, learned that Cornwallis was retreating with his army toward the Chesapeake Bay and Yorktown.

![Siège de Yorktown by Auguste Couder, c. 1836.[c] Rochambeau and Washington giving their last orders before the battle.](https://www.warhistoryonline.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/64/2018/08/siege-de-yorktown-by-auguste-couder-c-1836-c-rochambeau-and-washington-giving-their-last-orders-before-the-battle-725x640.jpg)

De Grasse and his forces were headed for Virginia with a plan to rendezvous with the Continental forces led by General Greene and Marquis Lafayette, who were headed south. Together their commands stopped Cornwallis army from creating havoc in Virginia, forcing his army toward the coast.

With the knowledge that the French fleet was heading toward Virginia, Washington projected his forces Southward in what he hoped might become a decisive victory.

While the American army progressed south, the most decisive naval battle of the war was taking place off the Virginia Capes between a French fleet under the command of De Grasse and a British squadron under the command of Admiral Hook. De Grasse’s forces pushed the British with greatly reduced numbers back to New York.

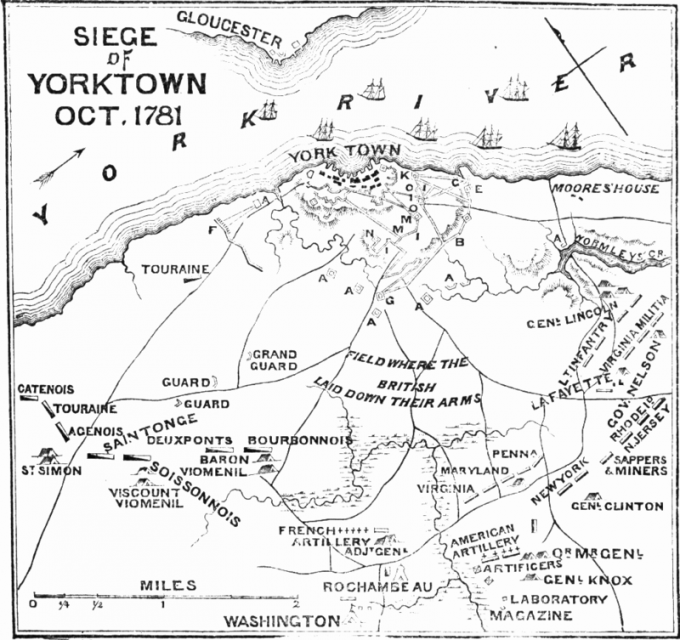

September 14 would see Washington’s arrival in Williamsburg, Virginia and two weeks later, the Siege of Yorktown began. In the early hours of September 28, Washington led his troops out of Williamsburg to surround Yorktown, placing his forces on the right while French forces took the left side.

For the first time in the war, the Americans held overwhelming superiority in every way, with their forces combined, the American and French armies boasted a staggering 19,000-man army against the remaining British 9,000. Fresh supplies and ammunition had also arrived with Washington and the sea was also now controlled by the Allied forces, setting the stage for a grand victory.

With everything now in their favor, Washington and Rochambeau both decided that the way to conquer Yorktown was through a classic siege and Cornwallis unknown to him, made their efforts a little easier when he consolidated his lines.

Trench digging began on 5 October under French supervision and cannons were placed four days later. Subsequently, the joint forces commenced bombardment of British defenses at Yorktown, firing 3,500 rounds every day and as a measure to extend their lines, they successfully took two British outposts on 14 October.

The night after the American and French forces captured the outposts, the British attempted a counter-attack to regain the outposts but were repulsed. Cornwallis was seemingly out of options and ultimately attempted to retreat from Yorktown but that ship had already sailed a long time ago. The British were now effectively trapped within the city.

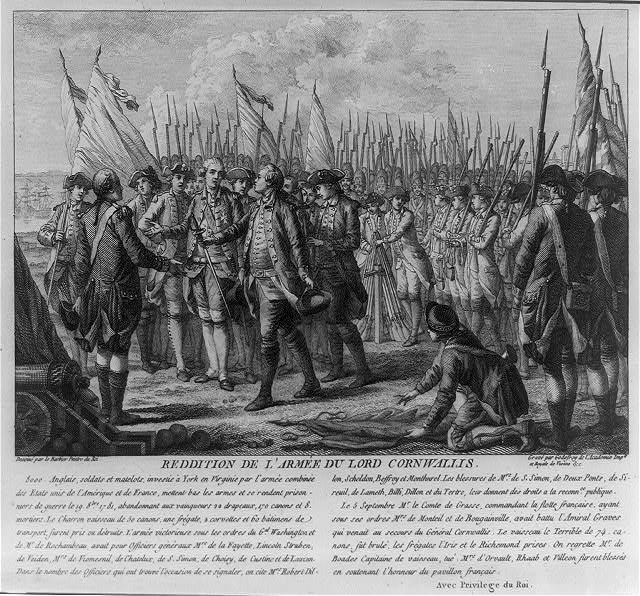

On 17 October, the Allied guns started the morning with heavy artillery bombardments against the British until a white flag was raised around 10 AM, indicating a British surrender. Subsequently, a British officer was escorted to Washington’s quarters where he gave a letter to the General proposing a ceasefire and surrender negotiations.

A meticulous Washington demanded to know the terms of surrender being proposed by Cornwallis. The rest of that day and the next would see negotiations from both parties. One officer in every fifty from the British Army was to be paroled and one ship would be allowed to sail to New York with deserters or whomever Cornwallis chose.

Celebrations began in the afternoon of 19 October with the British soldiers marching between two very long lines of Allied soldiers to surrender. The Americans captured 8,000 soldiers, 214 pieces of field artillery and thousands of muskets. The war effectively over, the Americans had gained their independence from British rule.