The Battle for Hamburger Hill left such a big mark on the American psyche that it has appeared in films, documentary series, video games and even a rap song.

It wasn’t just one of the bloodiest moments in the Vietnam War, but it marked the turning point in strategy and public opinion towards the conflict – and could even have contributed to the beginning of the end for the armed resistance against the communist forces in the country.

Maybe the press back in America could have tolerated the loss of life if Hill 937 was of strategic value, or if the military had kept and occupied it after costing so much to take it. Maybe if the top brass had planned better, or if friendly fire had not killed seven and wounded 53 of their own men things would have turned out differently.

But they didn’t, and US soldiers died from wounds caused by their own fire as well as those from the North Vietnamese forces.

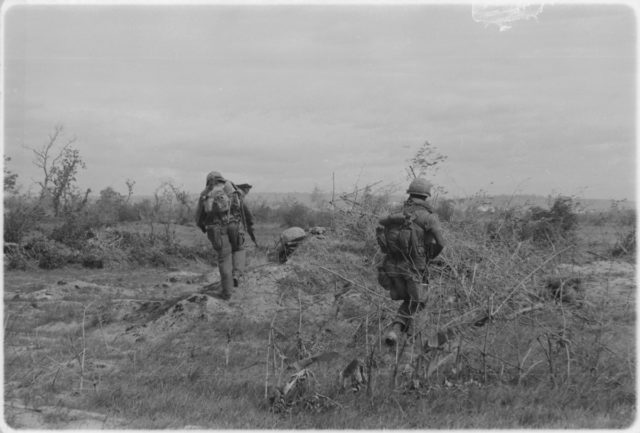

Because of the surrounding vegetation, the battle was mainly an infantry affair, with the U.S. Airborne troops moving against the well-entrenched enemy through the steep hillside and bad weather. The hill was eventually taken, causing much worse casualties to the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN).

The engagement came about due to Operation Apache Snow commencing, which had the aim of clearing the PAVN from the A Shau Valley in South Vietnam. This valley was situated near the border with Laos, and it had become a haven for the communist forces and a major infiltration route into the south.

This valley was heavily forested, and above it stood Ap Bia Mountain, otherwise known as Hill 937 – or Hamburger Hill. It was unconnected to the ridges that surrounded it, and it was covered in dense jungle like the valley that encapsulated it.

A three-part operation was planned to clear the area of enemy forces, and the second phase of that started on May 10th, 1969 as parts of Colonel John Conmey’s 101st Airborne, 3rd Brigade moved into the valley in the shadow of the hill that would claim so many lives.

Among the forces available to Conmey were the 3rd Battalion, 187th Infantry, 2nd Battalion 501st Infantry and the 1st Battalion, 506th Infantry. Supporting was the 9th marines and the 3rd Battalion, 5th Cavalry as well as parts of the Army of Vietnam (ARVN)

The engagement began when the ARVN cut the road off at the base of the valley, while their American allies pushed forward the Laotian border with the Marines and the 3/5th Cavalry.

The task of destroying the PAVN forces in the valley was given to the 3rd Brigade, who were ordered to take out any and all enemy soldiers in their zones. Because Conmey’s troops were air mobile, his plan was to move them around the battlefield quickly should one unit require assistance – and heavier contact was quickly established on the May 11th when the 3/187th got closer to the foot of Hill 937.

It was on this day that one of the most tragic events of the whole battle took place, and one that would have revolted and disgusted the public back in the States – as well as damaged morale among the forces in Vietnam.

Lt. Colonel Weldon Honeycutt had control of the 187th Infantry, and he sent Charlie and Bravo companies to move up towards the summit of Hamburger Hill on different routes. Later on during that day, Bravo came up against fierce resistance by PAVN forces and gunships were sent in to provide some much-needed fire support.

However, these mistook the landing zone used by the 3/187th landing zone for an enemy camp and opened fire on their own men. Two allied soldiers were killed from the skies, while another 35 were wounded. Tragically, this would not be the last friendly fire incident during the battle, as the thick jungle made life incredibly difficult for helicopter pilots. After this, the 3/187th bunkered down into defensive positions for the night.

The next couple of days were characterised by Honeycutt trying to push his units into place so they could coordinate with each other and launch a final attack. However, the terrain was incredibly tricky to navigate, and the resistance from the PAVN fierce made life difficult.

The Vietnamese enemy forces had constructed a series of bunkers and trenches which made it difficult both to advance and to count the number of casualties inflicted on the PAVN men.

As the battle shifted to Hill 937, Conmey moved the 1/506th to the southern side of the hill – and Honeycutt airlifted Bravo Company to the area, and the rest of the battalion made their way by foot and met up with the 1/506th and Bravo on the 19th of May.

Meanwhile, Honeycutt ordered attacks against enemy positions on the 14th and 15th of May, with little success. American progress was severely limited by the thick jungle, which also made it difficult to airlift forces around the battlefield and identify enemy forces for air attacks.

Finally on the 18th of May, Conmey coordinated an attack with the 3/187th and the 1/506th – as they hit Hamburger Hill from the north and the south. Delta Company from the 3/187th almost took the ridge, but they were forced back with heavy casualties by the Vietnamese, while the 1/506th had more success – taking the southern crest of Hamburger Hill, Hill 900, despite heavy casualties.

In light of this, the 101st Airborne commander Major General Melvin Zais arrived on the scene and immediately ordered three extra battalions to be committed to the battle – and ordered that the 3/187th be relieved. They had taken 60% casualties and were hurting from their engagements. Honeycutt protested at this, and forced his men to remain in the field.

Finally, Zias and Conmey launched a massive assault on the hill on the 20th of May at 10 am. The shattered 3/187th took the summit only two hours later, and at 17:00 the hill had been secured.

In total, the Allied forces suffered 70 dead soldiers and 372 wounded. The PAVN suffered much more, with at least 630 killed but probably far more. The engagement was covered extensively in the press back home, and when the 101st abandoned the hill on 5th of June, public and political pressure resulted in a change of strategy for the US effort in Vietnam.