Not only was the Battle of Khe Sanh one of the longest and bloodiest confrontations of the Vietnam War, it also kept American focus away from the impending Tet Offensive.

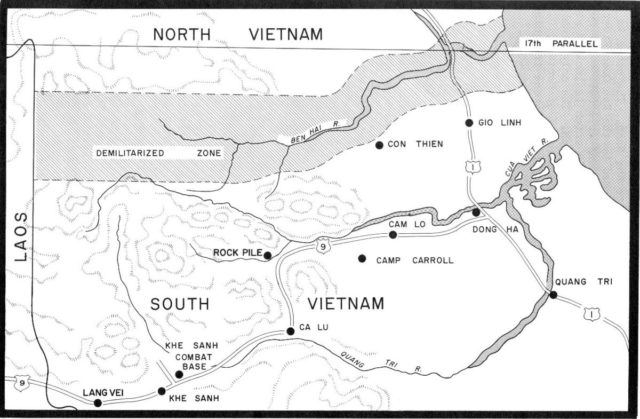

The battle began on the 21st of January, 1968, when the People’s Army of North Vietnam (PAVN) began a huge artillery bombing campaign against the U.S. Marine’s that were garrisoned at Khe Sanh, near the border with Laos in the northwest corner of South Vietnam.

American military presence in the area began in 1962 when special forces built a camp near the village. This initial building was 14 miles south of the demilitarized zone (DMZ), between the countries of North and South Vietnam in Quang Tri province and six miles away from the Laotian border on the main road between Laos and South Vietnam.

Communist forces wanted to occupy the area south of the DMZ in order to launch attacks into their neighbor’s territory and sow unrest in the region – but in order to do this, they had to take the fort at Khe Sanh.

Four years after the initial building in 1966, the U.S. Marines built a garrison opposite to the Army camp. One year later, PAVN forces began to build up their forces in the region and American officials began to think that Khe Sanh would come under attack imminently.

Those preliminary attacks began in 1967 but were repelled by the Marines. In the period of fighting that followed, U.S. forces secured three hills that surrounded the area and erected combat outposts.

The commander of the U.S. Military Assistance Command in Vietnam (MACV), General William Westmoreland, thought that Communist forces were about to go after Khe Sanh as part of the general effort to capture South Vietnam’s most northern areas to strengthen their hand for any future peace talks.

They had previously done this to French colonial troops at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu in 1954, just before gaining independence at the Geneva peace conference. To stop this, Westmoreland reinforced the garrison at Khe Sanh to around 6,000 as well as stockpiling ammunition and refurbishing the airstrip at the base.

However, this stockpile wouldn’t last long as it was destroyed during the first waves of the attack. On the 21st of January 1968, PAVN forces started a huge artillery bombing campaign that hit that ammunition store and sent 90% of the mortar and artillery rounds up in a huge fireball.

The defenders at Khe Sanh were forewarned of an attack. On the 20th of January, a PAVN defector told 26th Marine Regiment commander Colonel David Lownds that an assault would be carried out shortly.

True to his word, Hill 861 was attacked by a force of around 300 PAVN troops and the shelling of the fort began. The enemy action was repulsed, but they still managed to breach the Marines’ defenses and were only finally cleared from the hill after gruesome hand to hand fighting.

It wasn’t just American forces at the base who came under attack, but their allies from the Kingdom of Laos – who had stationed troops at Ban Houei Sane. On the 23rd of January, they were beaten back from the area, and the survivors fled to the U.S. Special Forces camp at Lang Vei.

It was also around this time that the men at Khe Sanh received their last reinforcements in the form of the more Marines and the 37th Army of the Republic of Vietnam Rangers Battalion.

As a response to those attacks in January, President Lyndon Johnson and Westmoreland agreed the base should be held at all costs and launched Operation Niagara – which was an artillery bombardment to try and knock out North Vietnamese heavy weapons in the hills surrounding the base.

Because Johnson and Westmoreland thought Khe Sanh was the main target of PAVN forces, they ignored the buildup of troops that would lead the Tet Offensive.

Just ten days after the attack began on Khe Sanh, Viet Cong and North Vietnamese forces staged brutal attacks on around 100 cities and towns in South Vietnam. The aim of this was to break the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN), bring the South Vietnam population to rebellion and cause divisions between American and her allies.

The American press kept referring to the battle as “another Dien Bien Phu,” although the Americans and South Vietnamese were able to call on helicopters and cargo planes to resupply their men – as well as B-52 bombers, who dropped 100,000 explosives on the enemy force during the siege.

This was the main aim of Niagara – to pound PAVN positions around the area to submission. Fighting did lull around the end of the month, but this was only because the Tet Offensive had kicked off then.

Attacks began again on the 7th of February and the camp at Lang Vei was overrun – the Special Forces that fled the scene made their way back to Khe Sanh.

In the final week of February, the fighting got worse as a Marine patrol was ambushed and attacks were launched. On the 25th, a ‘ghost patrol’ went outside the wire of the camp when they ran into a perfect ambush by Communist forces.

After pursuing three NVA soldiers into the jungle, the patrol from 3rd Platoon found themselves being cut down by enemy small arms fire and machine guns. It was one of the more lethal days for Bravo Company, who lost 27 killed and one taken prisoner. Of the 19 wounded, only eight would return to service.

Despite small victories like this, PAVN units began to withdraw from the area in March – even though the horrific shelling carried on, detonating the ammunition dump for the second time. At the end of the month, Operation Pegasus began, which was designed to break the siege.

This planned involved the 1st and 3rd Marine Regiments, who were to attack towards Khe Sanh while the 1st Air Cavalry used helicopters to seize key areas on the advance. As the Marines took more ground along the dilapidated Route 9, engineers were to repair it.

On the 6th of April, the Marines advancing towards the base met a large PAVN blocking force and a three-day battle ensued. When American units finally overcame their Communist enemy, they declared Route 9 to be open.

The defenders at the base were besieged for 77 days, during which time 703 Allied soldiers were killed, and 2,642 were wounded. Enemy losses are harder to estimate, but they stand at around 10,000 – 15,000.

However, the controversy didn’t end there as the decision was made to evacuate and destroy the base in July – under the orders of new commander General Creighton Abrams.

The question remains whether or not leaders in Hanoi wanted to take the site for military aims or to distract American forces from the Tet Offensive. Either way, it worked.