If you want to make a movie about the Vietnam War, there are a few stock things you need. Of course, you need the 60’s soundtrack: Hendrix’s version of Dylan’s All Along the Watchtower, Creedence Clearwater Revival’s Run Through the Jungle or Fortunate Son, maybe throw in some Rolling Stones and a Motown hit or two and you’ve got your soundtrack sorted.

Then you need jungle. Lots of it. Never mind that much of Vietnam is actually more forest and plains than actual jungle, but you need it for your movie anyway. It’s more atmospheric that way. You also need drugs and soldiers using drugs.

A bit of racial bonding after much tension. Officers that are complete idiots who the “grunts” want to “frag”. Lots of helicopters, some grass huts, Vietnamese in black pajamas. Now you’re all set.

One more thing: an American GI or Marine screaming on the ground with perhaps his foot blown off or a bamboo stake stuck in his side, and his comrades screaming at “Charlie” to come out and fight like men. Of course, these are all stereotypical. But the last scene of our fictitious movie begs the question: Why would they come out and fight??

For centuries, men have employed booby traps of one sort of another. Most but not all of the time, it is the weaker side that is using them in defense. In Vietnam, the Viet Cong guerrillas (the “VC”, or “Charlie”, as they were called by the Americans) and the North Vietnamese Army (“NVA”) were immeasurably outgunned by the forces of the United States and its allied contingents.

What air power the North Vietnamese possessed was kept in defense of the north of the country, particularly around the capital, Hanoi, and important infrastructure. Eventually, most of the North Vietnamese air force was shot down and air defense was mainly conducted by Soviet-supplied ground to air missile batteries.

North Vietnamese/VC armor was virtually non-existent. The VC and NVA possessed some artillery, but this was mostly mortars which could be easily carried by one or two men. Ammunition and other supplies mainly came down the so-called “Ho Chi Minh Trail,” which was bombed regularly and made supply inconsistent.

Arrayed against the Vietnamese was the most powerful armed force of the time. The United States dominated the air and the sea. In pitched battles, the Americans won virtually every time. Mountains of American ammunition, food, and equipment was stored in bases all over South Vietnam. Thousands of planes and helicopters roamed the skies over South Vietnam.

In 1968, half a million American troops were in the country.

With all that in mind, is it any wonder that the Viet Cong/NVA put great stock in booby traps? There are innumerable benefits to them, militarily speaking:

1) they’re cheap,

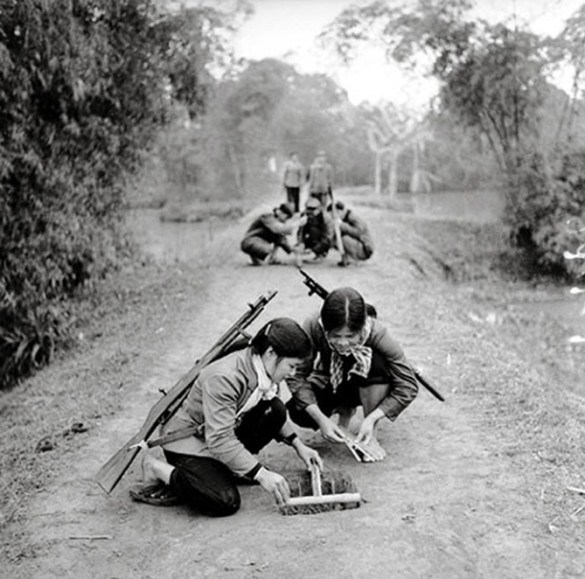

2) they are relatively simple to make and use, meaning that virtually anyone can make one,

3) many were not designed to kill, but maim, requiring other men to care and remove the wounded man. And a wounded man spreads the word about how he got wounded. It’s one thing to enter a battle that’s already raging; a soldier knows danger is present. Walking through the woods with no enemy for miles around on a nice quiet day, then suddenly getting your leg blown off? Psychologically terrifying.

4) most of the booby traps used by the VC worked on their own – no one needed to set them off or be around when they did.

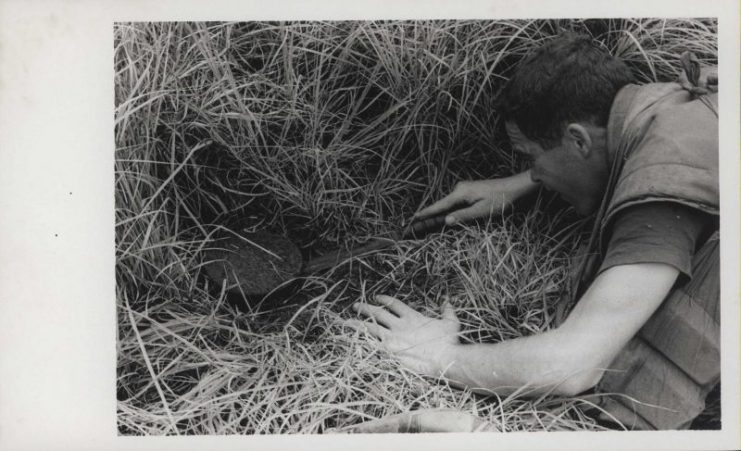

And 5), unlike most mines, many of the Viet Cong’s booby traps were made from bamboo – mine detectors couldn’t locate them.

According to statistics compiled by the Australian Ministry of Defence (Australia had men in Vietnam for almost the entire conflict), 11% of all deaths and 15% of all wounds in Vietnam were due to booby traps (this is for all Allied troops, including US armed forces). Counting US forces alone, there were over 300,000 wounded in Vietnam. That means about 45,000 men were injured by booby traps.

Of these wounds, 2% came from punji stakes, the most infamous of all the booby traps employed by the Vietnamese during the war. Sharpened bamboo stakes of various length and width, punji stakes could be used in a variety of ways, most infamously in camouflaged pits. What’s worse, they were often coated in human or animal waste, making them biological weapons – the intent being to cause infection in the victim.

Bamboo stakes could also be run through large balls of mud, which would then be left to harden in the sun. Suspended in trees by vines and triggered by a primitive tripwire (much like a hunter’s snare), these large maces would swing down at various heights with the intent of impaling the victim.

A more “modern” booby trap consisted of two cans fastened solidly to the ground and connected by a taut wire. Inside each can? A grenade whose pin had been pulled. Inserted into the can, the safety lever would be held down. When a soldier walked through the tripwire, the grenades were pulled from the cans, the safety levers sprung away, the fuse was ignited and then “BOOM!”

“Toe-poppers” were bullets/shells planted in the ground within a tube and over a nail. The tip of the bullet/shell would protrude from the ground (camouflaged, of course). An enemy would come by, step on the shell (which would strike the nail in the same way a gun’s firing pin did) and explode. Sometimes (in the case of larger shells) fatal, most often these traps left a man permanently disabled.

The Vietnamese made use of pressure release traps as well. In the famous movie “Platoon” (1986), a GI lifts an ammo case filled with maps he has just found in a hastily abandoned Viet Cong headquarters. When the case is lifted, an electrical charge was released, which ignited an explosive within, killing two men.

The VC/NVA learned to booby trap items not only of seeming military importance (like the maps in “Platoon”) but things that GIs often found of interest, such as flags. Leaving their flags flying or laying on the ground as they retreated, the Vietnamese would sometimes rig booby traps to go off when the flag was touched or lowered.

Aside from the infamous bamboo punji stakes (which were also used by the Japanese in WWII), the VC sometimes used another common feature of the landscape as a booby trap or psychological weapon – poisonous snakes. Nicknamed “Two-Step Charlie” (get bit by one, take two steps and keel over) by the Americans, a variety of venomous snakes were used as weapons.

Left in old weapons caches, or tied and left around corners in the various tunnel complexes dug by the Viet Cong, the snakes were not necessarily the most effective booby trap of the war but ranked high in terms of the fear the thought of finding one instilled.

During the course of the war, the Vietnamese perfected the “art” of the booby trap. This is but a small sampling of many different types deployed during the war, and which took such a profound physical and psychological toll on their enemy.