Whether considered graffiti, artwork, or simply bored doodlings of young men forced to be soldiers in a land far from home, a soldier’s helmet was as much his life as his rifle.

The Vietnam War tested the United States in new and horrid ways. Unprepared for guerilla tactics, dense jungles, and unwilling to interpret their foes’ actions as anything other than the working of Moscow’s efforts to expand Communism, the nation spent years in a conflict with no seeming end in sight.

Date between 1966 and 1971

Conscripted troops were constantly cycled through the war to prepare a generation for World War III, while politicians and commanders continually failed to understand the lessons learned in America’s previous guerilla campaigns.

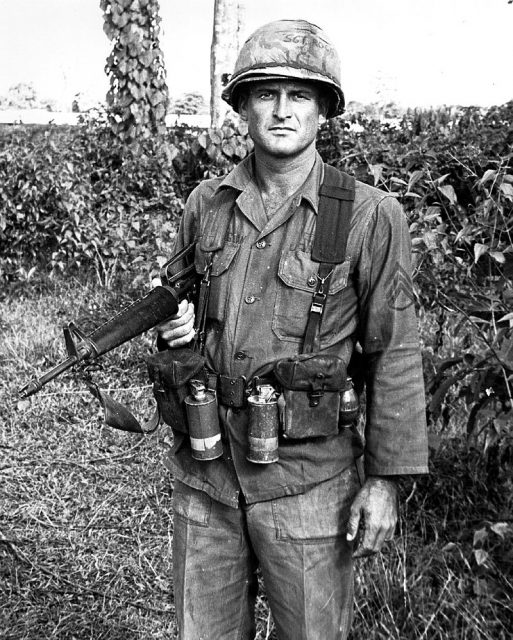

For the troops on the ground, Vietnam was a humid hell filled with enemies and a people barely considered human. Part of any soldier’s equipment at the time included a helmet, called a steel pot by the troops and officially known as the M-1 helmet.

The soldiers of Vietnam, being products of a time when the nation’s youth struggled to assert their individuality, started doodling on their helmets to express themselves.

Such antics were not new, as handfuls of soldiers did something similar during World War II. During Vietnam their work grew more prominent and noticeable. It also garnered more attention as outrage against the conflict, both among the troops and at home, increased.

Such artwork drew media attention as early as June 18, 1965. Appearing in an Associated Press article by Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer Horst Faas, the photo caption noted Larry Wayne Chaffin of the 173rd Airborne Brigade, sporting a simple line across the bridge of his helmet: “WAR IS HELL.”

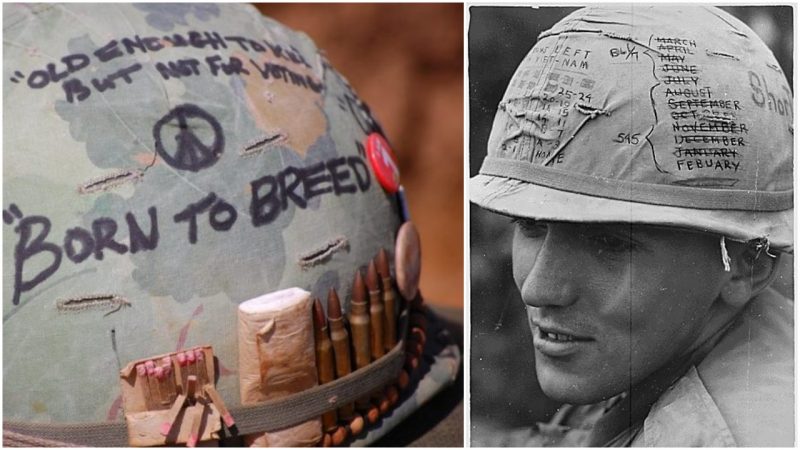

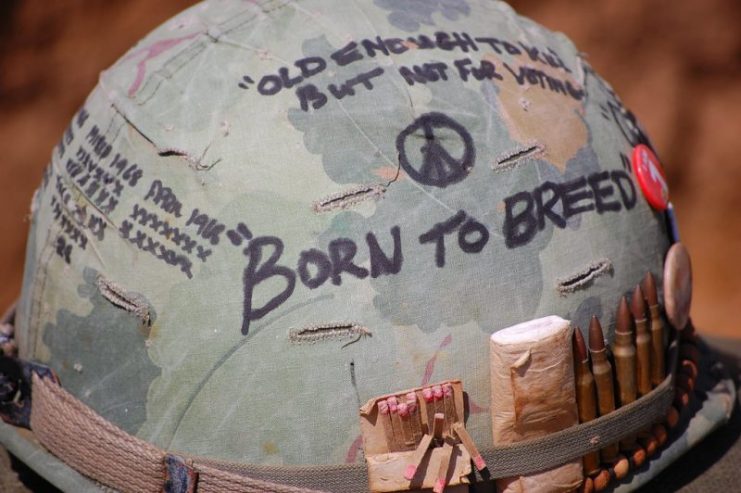

Simple calendars were a popular doodle, with soldiers jotting down the months of their tour and then crossing them off as time passed and they managed to live another thirty days. Such “short-timer” calendars were common among conscripts as they waited out their tours of duty.

The media, latching on to the potential anti-war messages of such art, made sure to showcase it as the conflict continued. One photograph from 1966 showed John Wayne signing a soldier’s helmet. Many photos recorded phrases and remarks written on soldier’s helmets, ranging from mottos such as “In God We Trust” to satirical musings like “Born to Kill Die.”

Not all such writings made it to the news. Years later on a web forum, one veteran told the story of his art:

“My personal helmet ‘graffiti’ was the moniker ‘Teenage K****r.’ As a recruit in Marine boot camp, we were repeatedly told a story of Eleanor Roosevelt reportedly telling someone she had found Marines to be “over-sexed, under-paid, teenage k****s.”

“One night, outside Da Nang, after imbibing a bottle of ‘Panther piss’, the phrase popped into my head and was promptly Magic-Markered onto the side of my ‘piss-pot’.

“It was greeted with mixed reviews by the higher-ups and I was ‘asked’ to make myself scarce when photographers were in the area. Sometime later, I was ordered to remove the ‘offensive’ phrase from my helmet cover. This was accompanied by a new helmet cover.

“I ignored the order, and the new cover, and was given an Article 15. With a grin, the 1st Sgt replaced my ‘salty’ with a new greenie.”

Whether considered graffiti, artwork, or simply bored doodlings of young men forced to be soldiers in a land far from home, a soldier’s helmet was as much his life as his rifle.

Read another story from us: Whittling Time Away: Trench Art of WWI

Whether their writings veered toward the crude, satirical, devout, or rambling, such works allowed them to express themselves as they fought a conflict for motivations more than likely lost on a bunch of overgrown kids stuck in the jungle.

Appropriate or not, their artwork lives on as a reminder of a war many people would rather forget.