War History online proudly presents this Guest Piece from Jeremy P. Ämick, who is a military historian and writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.

Following his graduation from a Kansas City, Missouri, area high school in 1967, Joe Dresselhaus was frequently turned down for jobs by employers concerned they would lose him to the draft. This reality, he explained, motivated his decision to complete a stint in the military so that he could approach an employer and say, “Now that I’ve been to Vietnam, will you give me a job?”

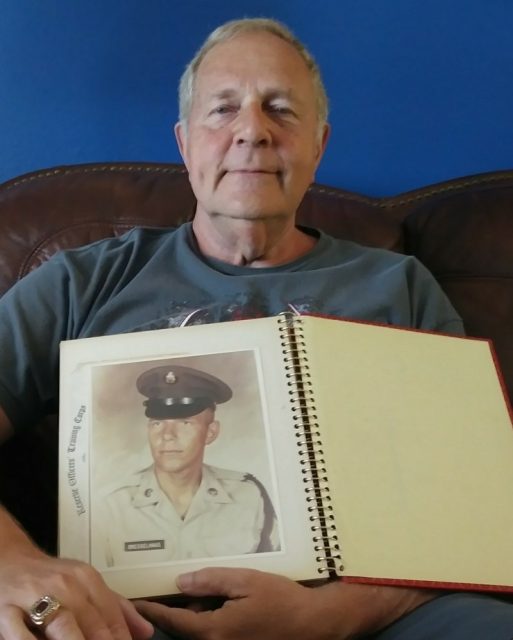

Enlisting in the U.S. Army in April 1969, Dresselhaus was soon on his way to Ft. Leonard Wood, Missouri, for his basic training. From there, he traveled to Ft. Sill, Oklahoma, where he received several weeks of training in artillery.

“At (Fort) Sill, we learned to fire everything from the 105s up to the 175s (105mm and 175mm howitzers),” he explained. “It wasn’t any type of training that I selected, the Army chose it for me because I guess they figured that’s where they needed me.”

During his training at Ft. Sill, the young soldier accepted an offer to become a “Shake ‘n Bake sergeant”—an intensive course of training in a combat specialty that allowed inexperienced soldiers to receive a rapid promotion to replace non-commissioned officers retiring from the Army or those who became casualties in Vietnam.

“I remained at Ft. Sill for several more weeks and trained as a 17E40 (the Military Occupational Code for a Field Illumination Crewman),” he said. “They taught us how to operate an infared searchlight that illuminated an area so that you could see in the dark through special scopes,” he added.

Graduating from training in March 1970, Dresselhaus was on his way to Vietnam less than a month later. Although a soldier in the U.S. Army, he was attached to an element of the 1st Marine Division stationed in a camp on Hill 270 southwest of Da Nang.

He explained, “The hill was on a saddle and if you followed the saddle out, you’d hit the Cambodian and Laos border,” he said. “We were like a plug in the middle of the road to stop the movement of enemy troops. The only way off the hill was to repel or by helicopter.”

During his time in the camp, one of Dresselhaus’ primary duties was to light up the perimeter at night with his infared search light, at which point the Marine Corps snipers and riflemen could spot enemy troops through their Starlight scopes.

He and his fellow Marines were later transferred to a site known as Namo Bridge, which spanned the Song Ca De River, to protect the bridge from destruction by enemy forces since it was along a major route used by American troops. It was here that the soldier received the first of two overseas injuries.

“To keep the enemy from sneaking up and setting satchel charges to destroy the bridge, we’d drop concussion grenades into the water in the course of the evening,” he said. “One evening, I pulled the pin and threw a grenade and it went off almost immediately because it didn’t have a fuse in it.”

He continued, “I woke up in the battalion aid station with ruptured ear drums. Had I held on to the grenade for another second or so, I would have been killed.” Pausing, he added, “I was back at work the next day.”

The final stage of his assignment in Vietnam was on Hill 65, which was again located southwest of Da Nang with the 1st Marine Division. It was during this timeframe, he noted, the Marines were beginning to rotate back to the United States as the U.S. Army arrived to take their place.

“I was coming back to Hill 65 from a trip to Da Nang while driving a Jeep with another soldier riding in the passenger seat,” Dresselhaus said. “I’m not sure what happened—whether we hit a mine or what—but the Jeep rolled several times and both I and the passenger were pinned underneath.”

It was approaching dark, he went on to explain, and their M-16 rifles were thrown clear of Jeep so they couldn’t defend themselves if attacked. Additionally, they were unable to reach the radio to call for help.

“Fortunately, some of our Marine friends showed up and were able to get us out from under the Jeep before it turned dark,” he said. “I was evacuated to the USS Sanctuary (hospital ship) in Da Nang Harbor and, thanks to the strength of my leg and Army combat boots, no bones were broken but it stretched and tore every tendon in my left foot.”

The soldier was sent back to the United States and finished out his enlistment at Ft. Leavenworth, Kansas, receiving his discharge in April 1971. After returning to Kansas City, a friend encouraged him to apply for a position with the Kansas City Police Department (KCPD), from where he retired in 1996 as a homicide detective after 25 years of service.

Shortly after his retirement from the KCPD, he and his family moved to Jefferson City, where he was employed for 14 years investigating murders for the Missouri Attorney General. The married father of four children has since permanently retired.

In reflecting on his time spent in the Army while assigned with the Marines in the Veitnam War, Dresselhaus noted there were incidents that provided him with an enduring level of appreciation for the country that is his home.

“When I was with the Marines at Namo Bridge, there was an elderly Vietnamese man who brought his granddaughter—a young girl who was probably 12 or 13 years old and needed medical attention. She had been shot through the hand and what was most unforgettable was that she wasn’t in shock … she was calm through it all.

“We realized that at her age and at that point in the Vietnam War, she had never seen a day of peace in her country and they were accustomed to such situations.” He added, “That experience is one that has stuck with me over the years and made me appreciate just how well we have it in this country.”