Operation Linebacker II was the ultimate oxymoron and a repetition of a favoured American tactic for bringing about peace on an Asian battlefield.

Just like when U.S forces resorted to dropping two nuclear warheads on Japanese civilians to bring about the end of the World War II in the Pacific, American commanders signed off on the heaviest bombing campaign of the Vietnam war – all to bring about the end of the conflict.

Before the scheme to force the North Vietnamese government into peace terms, there were three years of secret peace talks in Paris between Hanoi and President Nixon.

In October 1971, the Communist government changed their negotiating stance to come to an agreement with Nixon and Henry Kissinger. One of the reasons this switch was made was because North Vietnam thought an agreement would be easier to reach before, rather than after, the U.S election.

All this was done behind the backs of the South Vietnamese government, but despite this Kissinger held a press conference in October 1972 and recklessly declared that peace was at hand.

It would have been, if the South Vietnamese government had been included in the talks or looped into the decisions made behind closed doors in Paris. President Thieu was outraged that such an important decision was made without his support and behind his back.

Thieu refused to accept the peace treaty unless there were changes made to it. Significant changes. Peace hadn’t just been thrown off the table; it had been thrown out of the house and frog marched down the street.

By November, a list of 69 changes had been presented to the North Vietnamese delegation. They took one look at the new proposals and broke off negotiations completely, leading to the complete breakdown of peace talks.

But because of the statement that Kissinger made to the press earlier in the year, Nixon felt that he had no choice but to try and drag the communist powers back to negotiate a peace agreement. The public expected it now and were weary of the war that had dragged on for the best part of 10 years.

And that’s why, in December 1972, Nixon ordered a 12-day bombing campaign called Operation Linebacker II, otherwise known as the Christmas Bombings or the December Raids. The objective of this was to force the Politburo back to the negotiating table and to prove to Thieu that America hadn’t abandoned their support for his government.

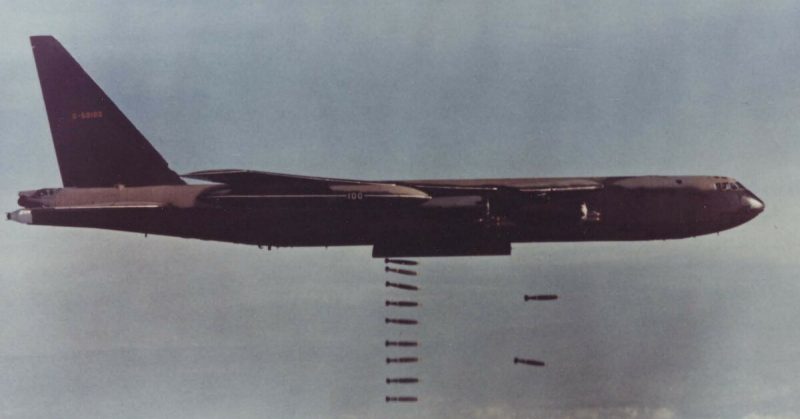

Because of the original Operation Linebacker, the Americans had a considerable force of B-52 bombers available to them. Strategic Air Command was initially reluctant to release half of the bomber force into use on one operation for a number of reasons.

One was because they didn’t want to risk the destruction of the expensive machines and the deaths of those highly trained airmen who flew in them. Secondly, the production line for these flying fortresses had been shut down, and replacement aircraft would not be able to be produced.

However, there were those within SAC that welcomed the chance to test the B-52 against more sophisticated air defences of the type the Soviets would be able to deploy if the Cold War boiled down to armed conflict.

The more gung-ho elements within the US Air Force won the day, and Operation Linebacker II was given the all clear to begin carpet bombing the civilian population and military targets around Hanoi and Haiphong.

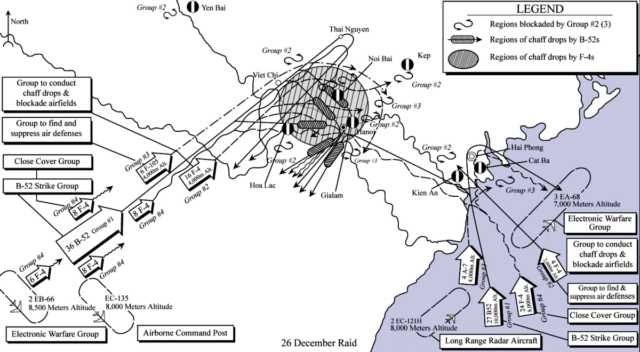

And so it was that between December the 18th to the 29th, B-52 bombers hit targets around those two areas with F-111s providing strikes on SAM surface-to-air missile sites and military airfields at night.

During the day, A-7 and F-4 aircraft carried out bombing raids using visual or long-range navigation techniques, depending on the weather, while EB-66s and EA-6s provided an escort to the bombers and KC-135s were used to provide in-flight refueling.

The first three missions of Operation Linebacker II were flown as planned, beginning on the 18th of December. On the first night, 129 bombers were launched, along with 39 support planes to provide fighter escorts as well as radar jamming capabilities.

Bombs hit targets at three North Vietnamese airfields, as well as a warehouse complex located at Yen Vien. The second and third waves of the attack hit targets around Hanoi itself, as three planes were shot down by North Vietnamese SAM batteries.

The same evening, a further aircraft was shot down while on a bombing run that targeted the broadcasting towers of Radio Hanoi.

93 missions were flown the following night to target places like the Thai Nguyen thermal power plant and the Kinh No Railroad as well as the Yen Vien complex. This time, no bombers were struck down, although a number were damaged.

But from hubris comes nemesis, as the USAF found out when they launched their raids on the third night. Because of the limited casualties, high command thought things would go as smoothly as they had on the previous night.

A number of factors, from the repetitive tactics to the limited jamming capability led to all hell breaking loose. Eight B-52 aircraft were lost the night after North Vietnamese troops anticipated the strike pattern of the bombers and launched 34 missiles into the strike area. Only two out of those eight downed crews were rescued.

The shooting down of 12 bombers caused SAC commanders to change their tactics. They had anticipated more resistance from MiG fighter pilots and had not varied their flight paths, altitudes or flight paths to announce for ground-based anti-aircraft threats.

At this point, Nixon ordered the mission be extended past its three-day deadline, and American tactics changed dramatically. With this change, the amount of friendly casualties dropped significantly as F-111 fighter jets were sent on SAM site suppression missions, while bomber raids tended to avoid Hanoi.

One real tragedy of the bombing campaign was when the Bach Mai hospital was hit by a wayward string of bombs. 28 doctors, nurses, and a pharmacist were killed, which was turned into a cause celebre by peace activists and the North Vietnamese.

Operation Linebacker II was given a 36 hour period over Christmas when they flew no missions, but then American forces stepped up their bombing effort up to the 29th of December – at which point there were few strategic targets left to hit in North Vietnam.

But seven days before, on the 22nd of December, diplomats in Washington asked their communist foes to come back to the negotiating table.

Hanoi consented, but made it clear that it wasn’t because of the intense bombing. Nevertheless, Nixon suspending bombing on the 30th of December, while Kissinger agreed to the initial terms of the ceasefire that had been thrashed out in October.

After some convincing, Thieu agreed to those terms and an agreement was finally struck on the 9th of January. In total, 741 bomber sorties had been flown, and over 15,000 tonnes of ordnance had been dropped on their targets. 33 B-52 crew members were killed or missing, 33 became prisoners of war, and 26 others were rescued.

And all because of the breakdown in talks several months earlier. The real tragedy of the story is that the terms agreed to in January were almost exactly the same as the ones rejected in March. All that loss of life had been for nothing.