Looking back at the First World War there are many events and that spark controversy to this day and mysteries to be cleared up. We are looking at 10 of these and try if we can make sense of them.

1. Who Fired The First Shot?

Austro-Hungarian River Monitor Shelling Belgrade

Austro-Hungarian River Monitor Shelling Belgrade

Most people think the first battle of World War One took place on 5 August 1914, when Germany invaded Belgium. The first fighting, however, occurred nine days earlier on the night of 28 July, mere hours after Austria-Hungary’s declaration of war against Serbia. This battle was an

Most people believe the first battle of the war began on August 5, 1914, when the Germans invaded Belgium. The very first skirmishes though actually took place nine days earlier on July 28, hours after Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia. The skirmish involved an amphibious assault attempt to take the Serbian capital of Belgrade.

The British war effort is less clear on who fired the first shots. As per the Daily Mirror, Corporal E. Thomas of the 4th Dragoon Guards fired the first shots on August 22, 1914. Thomas was a member of a 120-person force sent to investigate German cavalry advances in the Belgian village of Casteau. At 6:30 am on August 22, 1914, Thomas and his squad encountered a unit of 4 German cavalrymen who they engaged in combat. Thomas fired the first shot. History is unclear if anyone actually died in this skirmish.

The Australians, however, lay claim as the first to actually fire shots on behalf of the British Empire during the war. As per ABC News, within four hours of the British joining the war on August 5, 1914, the Australians fired the first shots of the war 17,000 kilometers away from the European Theater at Point Nepean when a German cargo ship named the SS Pfalz tried to leave Australian waters.

The SS Pfalz was just 10 minutes shy of escaping Australian port for open seas when Australian artillery headquarters received orders to stop or sink the ship.

Upon receipt of orders, gunners at Fort Nepean fired a warning across the SS Pfalz bow. This came as a surprise to Australian pilot Captain Montgomery Robinson who was on the Pflaz as a guide to navigate them out.

Relates Mr. Graynor of the incident, “So for a second or two there was a physical tussle on the bridge [of the ship] between the German captain and the Australian pilot. The pilot was adamant that they must stop because the next shot was going to be into the ship.” The Pfalz surrendered.

2. Who Killed Jon Parr?

John Henry Parr was a British soldier. A private, he is believed to be the first British soldier killed in action by enemy fire during the war.

A reconnaissance cyclist, Private Parr specialized in riding ahead of his unit to uncover information about the enemy or other necessary intelligence and then returning with all possible speed to update the commanding officer. Upon the start of the war in August 1914, Parr’s battalion was moved from Southampton to Boulogne-sur-Mer, France. When the German Army started its advance into Belgium, Parr’s unit settled in near the village of Bettignies alongside the canal in the town of Mons. On August 21, Parr and another cyclist were sent forward to the village of Obourg which is north east of Mons and over the Belgian border to locate the enemy. Most believe that they encountered a cavalry patrol from the German First Army and Parr stayed behind to hold them off while his partner rushed back to deliver their report. It is believed Parr was killed in the ensuing battle.

What truly happened to Parr remains a controversy to this day. What is known is that he was killed in action, but because the British army retreated to a new position around the Marne following the battle of Mons, Parr’s body was left behind. In the months that followed because of the nature of trench warfare news and accounting of Parr’s death was not recognized till much later. After not hearing from him for a while Parr’s mother wrote to the army inquiring on his status. The army was not able to tell her of his condition. It is believed that at the time they may have believed he had been captured. During that period dog tags did not exist to help ID casualties. The true circumstances of Parr’s death remain a secret in history. With the front line 11 miles away it is just as luckily he died from friendly fire vs a German patrol encounter or the Battle of Mons itself on August 23.

Parr was recovered, identified and buried in the St Symphorien military cemetery, just southeast of Mons. His gravestone marks his age at 20 as the army was unaware of his true age of just seventeen. Almost poetically, his grave faces that of George Edwin Ellison, the last British soldier killed during the Great War.

3. What Happened To The USS Cyclops?

The USS Cyclops (AC-4) was the first of four Proteus-class ships built for the United States Navy in the years preceding World War I. Named after the mythical race of one-eyed beings in Greek mythology, the Cyclops was the second U.S. navy ship to bear that name. On or shortly after March 4, 1918, the ship and her crew of 306 simply disappeared off the face of the earth in the area known as the Bermuda Triangle. Till this day it remains the single largest loss of life in U.S. naval history not involving direct combat.

As the disappearance occurred during a time of war, it was theorized she was captured or sunk by a German raider or U-boat because she was carrying 10,800 long tons of manganese ore used to produce munitions. At the time and in the years since the German government has consistently denied knowing anything with regard to the vessels whereabouts. Officially, the Naval History & Heritage Command has stated that she “probably sank in an unexpected storm” but the true and ultimate cause of the ship’s fate is unknown.

On March 10, 1918, the day after the ship was rumored to have been sighted by Amolco, weather reports indicated that a violent storm swept through the Virginia Cape area. Many believed that a combination of overload, engine troubles, and bad weather lead to the Cyclops sinking. However, the extensive naval investigation concluded: “Many theories have been advanced, but none that satisfactorily accounts for her disappearance.” Bizarrely, though, this finding was reported before Cyclop’s two sister ships, the Proteus and Nereus, also vanished in the North Atlantic during WWII. Much like their sister, both ships were transporting heavy ores similar to those the Cyclops carried on her final, fateful voyage. Like the Cyclops, theories were raised that their loss was the result of things ranging from catastrophic structural failure to bizarre mysteries of the Bermuda Triangle herself.

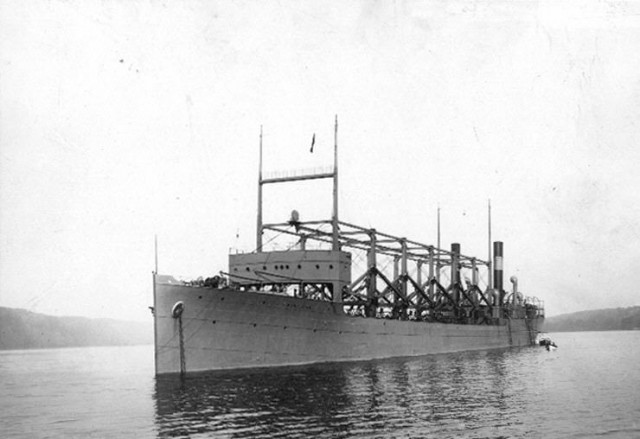

4. What happened to the Lost Treasure Of The Tsars

The story of the Tsars gold has transcended to the status of legend amongst treasure hunters. Debaters have varying opinions of what exactly happened and where the treasure is located. The known facts of the case are as follows. At the height of the Russian Civil War, the White Army named Admiral Alexander Vasilievich Kolchak as the Supreme Ruler of the Russian state. His crowning as the anti-communist leader was backed by a large portion of the Russian governments gold reserves which the White Army transported from Kazan to Omsk. The gold was estimated to be worth 650 million rubles ($20.8 million) by a bank in Omsk. Following Kolchak’s defeat in 1921, the gold was returned to the government. An inventory found bullions missing with an estimated value of 400 million rubles ($12.8 million).

So what exactly did happen to the 250 million rubles ($80 million) that was unaccounted for? According to an Estonian soldier named Karl Purrok who had served in Kolchak’s army in a Siberian regiment, they unloaded the gold at Taiga train station near the town of Kemerovo and buried it nearby. In 1941 the NKVD (Soviet Secret Police) located Purrok and ordered him to travel with investigators to locate the Siberian stash. Despite numerous excavations and attempts they were never able to locate the stash. It is still out there waiting to be claimed by a lucky treasure hunter.

5. The Flaming Onions

The mysterious ‘flaming onions’ instilled fear into WWI fighter pilots because no-one knew what they were and they out maneuvered regular aircraft making pilots unable to take evasive action.

Cambridge historian Denis Winter describes in this book, “The First of the Few” that the flaming onions “green glowing balls which twisted about like live things and seemed to chase an aeroplane, turning over end on end in a leisurely way.”

What it actually was, was a 37 mm revolving-barrel anti-aircraft gun used by the Germans. From a technical standpoint, it was a Gatling type, smooth bore, short barreled automatic revolver. Nicknamed a ‘lichtspucker’ (light spitter), it was designed to shot flares at low velocity in rapid sequence across a battle area. The gun had five barrels and had capabilities of launching 37 mm artillery shells five thousand feet. To help maximize chances of connecting with a target, all five rounds were discharged as rapidly as possible, thus producing the “flaming onion” visual and effect. Anti-aircraft artillery of the time fired very slowly. Because the flaming onion fired rapidly, many pilots thought the rounds were attached to a string and feared being shredded by it in the process. Not designed for anti-aircraft use, the weapon did not have purpose-designed ammunition, however, the flares would have been dangerous to fabric-covered aircraft.

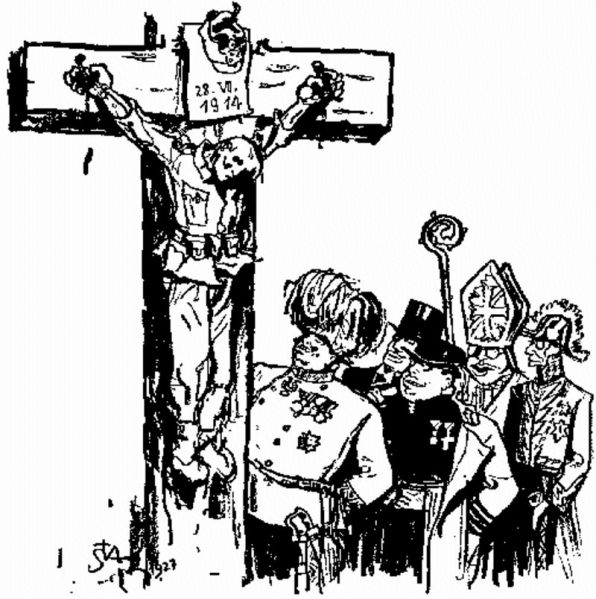

6. The Vanished Battalion of Gallipoli

By 1915, The Great War was a year old, and a coalition of British, Australian and New Zealand troops were deployed at Gallipoli on the Dardanells in Turkey with a mission to take the Turks out of the war. Amongst the coalition fighters were 250 soldiers and 16 officers from the Royal Norfolk Regiment. This fighting group was composed of servants, grooms, and gardeners from the British Royal family estate, at Sandringham in Norfolk.

The air was full of enemy fire on August 12, 1915, when the Royal Norfolk Regiment was ordered to advance against the Turks. Tired, hungry, thirsty and sick, the men made a mistake and turned the wrong way getting separated from the larger 163rd Brigade they were a part of. Even once they realized their mistake, they continued to advance against the Kavak Tepe ridge despite having no support or reinforcements. They were immediately gunned down by machine gun fire and picked off by snipers both on the ridge and up in the trees. Despite the odds, the Norfolk Regiment pressed forward through all the blood and bullets actually pushing back the enemy towards the forest which by then was engulfed in flames from the artillery fire. Beauchamp and the Norfolk continued to charge into the burning forest and would vanish into history never to be seen again. It is the image of these brave men pressing on through the smoke and trees that raises the lost Royal Norfolk Regiment into immortality.

Most believe the men were captured by Turkish forces and became POWs. Through the duration of and even after the war, the British government inquired with the Turkish government as to the whereabouts of the Royal Norfork Regiment, but the Turks consistently denied any knowledge of them.

7. Who Killed the Red Baron?

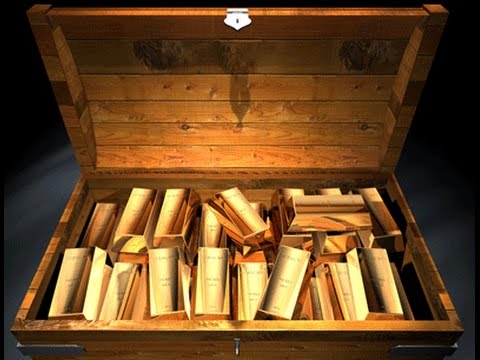

The infamous Red Baron, Manfred Albrecht Freiherr von Richthofen, was a German fighter pilot and widely renowned as the greatest flying ace of The Great War with an official record of 80 air combat victories. The Baron was shot down and killed near Amiens on 21, April 1918.

Who exactly was it that took out the greatest fighter pilot of the era? Controversy and contradictory hypotheses continue to reign.

Though at the time the Royal Air Force credited Roy Brown as the pilot who bested the Red Baron, it is now generally agreed that the bullet that killed him was shot from the ground. Richthofen died as a result of a fatal chest wound from a single bullet that penetrated his right armpit and resurfaced next to his left nipple. Brown’s attack came from behind and above to Richthofen’s left.

Most conclusively, studies showed that it was near impossible for The Baron to have continued his chase of May for the amount of time he did (up to two minutes) had his wound actually came from Brown’s guns. Various sources, including a 1998 article written by physician and military medicine historian Geoffrey Miller and a 2003 PBS documentary, believe the fatal shots came from Sergeant Cedric Popkin. An anti-aircraft (AA) machine gunner with the Australian 24th Machine Gun Company, Popkin is believed to have killed The Baron with his Vickers gun. On two occasions he shot at Richthofen. The first occasion was as the Baron was heading straight at his position. The second time was at long range from the right. Due to the nature of Richthofen’s wounds, Popkin was in the position to fire the fatal shot, when the The Baron passed him for a second time, on the right. Some confusion does exist due to a letter that Popkin wrote, in 1935, to an Australian official historian. In his letter, Popkin stated his belief that he had fired the fatal shot as Richthofen flew straight at his position. In this latter respect, Popkin was incorrect: the bullet that caused the Baron’s death came from the side.

In 2002, Discovery Channel published a documentary naming Gunner W.J. “Snowy” Evans as the actual shooter. Evans was a Lewis machine gunner assigned to the 53rd Battery, 14th Field Artillery Brigade, Royal Australian Artillery forces. Miller and the PBS dismiss this claim because of the angle from which Evans fired at Richthofen.

Still, other sources have suggested that Gunner Robert Buie (also of the 53rd Battery) as the soldier to have scored the fatal shot. There is very little support for this claim. In 2007, a municipality in Sydney recognised Buie as the man who shot down The Red Baron, placing a plaque near Buie’s former home. Buie, who passed away in 1964, has never been officially recognized in any other way.

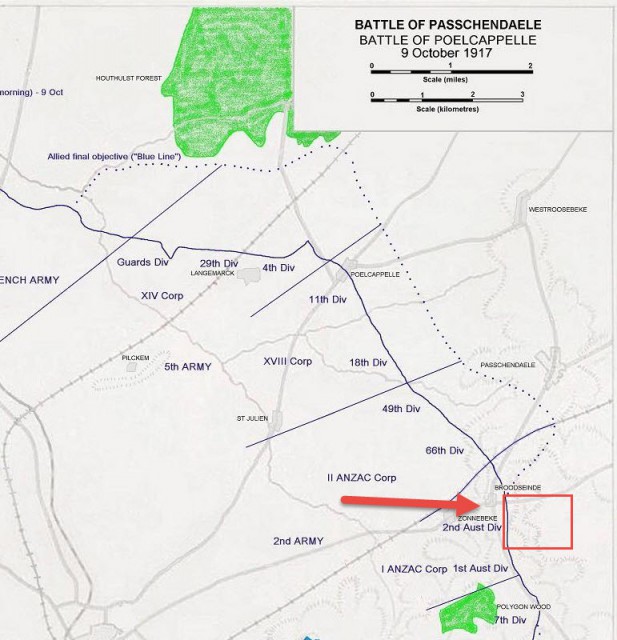

8. The Mystery of Celtic Wood

At the Battle of Poelcappelle which was fought on October 9, 1917, in Celtic Wood, Flanders, seventy-one (71) soldiers from the 10th Battalion of the 1st Australian Division disappeared without trace. Originally the plan called for the 10th to charge the woods, blow up German dugouts and pull back on a flare signal.

The 2nd Division would stage a large assault on the 10th’s northern flank to help defend the flanks of the main British advance force on its own northern flank. To further confuse the Germans, the troops attacked at dawn instead of at night to make them think the attack was part of the main advance.

Lieutenant-Colonel Maurice Wilder-Neligan, 10th Battalion commander, wrote the following in a report of the action, “…a desperate hand encounter followed; in which heavy casualties were inflicted upon the enemy…I am only able to account for 14 unwounded members of the party.” A survivor reported that only seven survived to return to Australian lines. Another said 14 survived. Official army records report that 37 of the 85 involved as missing without trace.

The official German records do not mention the attack which leads to speculation that men were massacred and buried en masse. Rumors persist to this day that the soldiers simply walked into the mist and vanished without a trace. Observers attribute the lack of record of the missing to confusion, miss-reporting and clerical error.

9. The Angel of Mons

Between 22–23 August, 1914, the British Expeditionary Force fought their first major engagement of the First World War at the Battle of Mons. Though heavily outnumbered and suffering heavy casualties forcing a retreat, they pushed back the advancing German troops. The retreat was perceived by the British public as a key moment of the war. Despite ongoing censorship at the time, the Battle of Mons was the first sign the British people had that stopping the Germans was not going to be as easy as some had believed.

On 29 September, 1914, Arthur Machen, a Welsh author, published a short story entitled “The Bowmen” in London’s The Evening News newspaper. Inspired by news accounts he had read of the Battle of Mons along with a series of factual articles he had written on the battle for the paper, Machen’s tale described phantom archers from the Battle of Agincourt summoned forth by a soldier invoking St. George, destroying the Germans. The story was set during the retreat from the Battle of Mons in August 1914. Despite the fact that it was, Machen’s story was not labelled as fiction.

The British Spiritualist magazine printed a story on April 24, 1915, recounting stories of a supernatural power that miraculously intervened to help British fighters at a key moment during battle. The article resulted in a continued and rapid flurry of similar accounts and continued the spread of wild rumors. Descriptions of the apparitions varied from everything from medieval longbow archers fighting alongside St. George to a strange luminous cloud. The most popular accounts though was of a host of angelic warriors. Stories of similar battlefield sightings have recurred through both ancient and medieval warfare.

By May 1915 controversy was in full-swing with the angel sightings being used as proof of divine intervention in favor of the Allies in sermons throughout Britain with subsequent publication into newspaper reports published widely across the world. Machen, amused at what was happening, sought to end the rumors by republishing his original story in August in book form. He wrote a long preface debunking the stories as false and how they originated in his story. The book became a bestseller and resulted in a vast series of other publications claiming to prove evidence of the Angels’ existence. Machen continued to try to set the record straight, but many saw the attempts to downplay such an inspiring tale as blasphemous and treasonous. The new works included popular songs and artistic renderings of the angels. Reports of other angels and apparitions continued to persist from the war front including that of Joan of Arc.

The only credible evidence of visions from the frontlines from actual soldiers serving on the front were those of phantom cavalrymen, not angels or bowmen. These reports occurred during the retreat rather than during the actual the battle itself. These particular apparitions did not intervene to attack or deter German troops which was a key element in Machen’s tale and the later reports of angels. As by the time of retreat most troops were exhausted and had not slept properly for days, and if one is already skeptical of the supernatural, the visions can be attributed to being mere hallucinations.

10. Crucified Soldiers

Austrian war veteran and artist Arthur Stadler (1892-1937) drew this crucifixion of a soldier in 1927.

Arthur Stadler (1892-1937), an Austrian war veteran and artist made this rendering of the crucifixion of a soldier in 1927.

The Times printed a short article entitled “Torture of a Canadian Officer” on May 10, 1915. The piece was attributed to a Paris correspondent.

According to the story, wounded Canadian soldiers at Ypres reported of how one of their officers was crucified to a wall “by bayonets thrust through his hands and feet” after which another bayonet attack was pushed through his throat before he finally shot and “riddled with bullets”. The soldiers shared that the events had been observed by the Royal Dublin Fusiliers and that they had overheard the Fusiliers’ officers discussing it afterward.

Two days later, on May 12, Sir Robert Houston asked Harold Tennant, the Under-Secretary of State for War, during a session of the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, “whether he has any information regarding the crucifixion of three Canadian soldiers recently captured by the Germans, who nailed them with bayonets to the side of a wooden structure?” In response, Tennant shared that no such incident had been reported to the War Office. Houston followed up by asking if Tennant was aware that Canadian officers and Canadian soldiers who witnessed the events of concern made affidavits and whether or not the officer in charge at Boulogne had reported it to the War Office. Tennant replied that inquiries would be made.

A few days later on May 15, The Times printed a letter from an army member. He shared the crucified soldier was a sergeant who was found transfixed to the wooden fence of a farm building. The letter recounted he had repeatedly been stabbed with bayonets leaving numerous puncture wounds in his body. The unnamed correspondent had not heard that the crucifixion had been witnessed by any Allied forces. He commented that it was possible that the man had already been dead by the time he was crucified.

The Canadian chief censor, Colonel Ernest J. Chambers, began an inquiry into the story soon after it began circulation. In his search for eyewitnesses, he met a private who testified under affidavit that he had observed three Canadian soldiers being bayonetted to a barn door just three miles from St. Julien. However, sworn testimony from two British soldiers who testified having seen “the corpse of a Canadian soldier fastened with bayonets to a barn door”, was debunked when it was discovered that the part of the front the events were set had never under German occupation.

The tale made headlines worldwide with the Allies repeatedly using the incident in their war propaganda. A U.S. propaganda film called The Prussian Cur (1918) produced by the Fox Film Corporation includes scenes of an Allied soldier’s crucifixion. Contemporary theories hold that the story is mere propaganda intended to make the German army look bad.