Co-organized by the American Jewish Historical Society in New York

Exhibition is first to illustrate how three events of a single year—America’s entry into World War I, the Bolshevik Revolution, and the signing of the Balfour Declaration—triggered fundamental changes that still impact the world today.

The National Museum of AmericanImage Jewish History (NMAJH) will debut the special exhibition 1917: How One Year Changed the World from March 17 through July 16, 2017. The exhibition looks back 100 years to explore how three key events of 1917—America’s entry into World War I, the Bolshevik Revolution, and the issuing of the Balfour Declaration, in which Great Britain indicated support for a Jewish homeland in Palestine—brought about political, cultural, and social changes that dramatically reshaped the United States’ role in the world and provoked its most stringent immigration quotas to date. The exhibition examines this consequential year through the eyes of American Jews, who experienced these events both as Americans and as part of an international diaspora community. Following its run at NMAJH, 1917 will be on view in New York at the American Jewish Historical Society, September 1 – December 29, 2017.

“The conflicts and consequences of 1917 are often overshadowed by later events, but they determined so much about the world as well as American and Jewish experiences thereafter,” says Josh Perelman, NMAJH’s Chief Curator and Director of Exhibitions & Collections. “While the exhibition is anchored in the past, it has powerful relevance to contemporary issues we are facing today, as a nation and as individuals.”

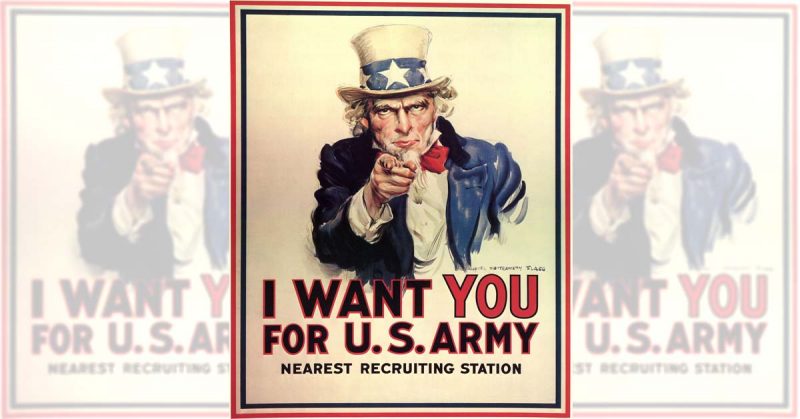

ImageThrough nearly 125 artifacts—including uniforms, letters, photographs, and posters—as well as films, music, and interactive media, 1917 takes visitors on a journey into WWI trenches, revolutionary Russia, and debates over the future of Britain’s colonial empire in the Middle East. The public has the rare opportunity to view two original drafts of the Balfour Declaration, never before exhibited in the U.S. Other highlights include a decoded copy of the Zimmermann Telegram, which helped propel the U.S. into WWI; a 1919 copy of the Treaty of Versailles, the agreement ending the war; an Uncle Sam costume, likely used during patriotic wartime events; and the Medal of Honor posthumously awarded to Jewish WWI soldier William Shemin in 2015. Visitors will also see Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis’s judicial robes and chair nameplate, a postcard written by a young Golda Meir describing the American Jewish Congress in Philadelphia, and a letter from the newly formed Soviet government’s Commissar of Foreign Affairs Leon Trotsky, constituting the U.S.’s first formal notification of the establishment of the Soviet Union. The exhibition concludes with a page from the original Johnson-Reed Act of 1924, an act to “Limit Immigration of Aliens into the United States for Other Purposes.”

Before the United States entered World War I on April 6, 1917, Americans debated whether the U.S. should join the conflict. Jews anguished over the security of European Jewish communities while also coping with growing intolerance of ethnic minorities at home. Nearly 250,000 Jews eventually served in the armed forces during WWI, including composer Irving Berlin, Corporal Eva Davidson, and posthumous Medal of Honor recipient William Shemin. While many immigrant communities expressed their patriotism in the Armed Forces and on the home front, they still faced a political climate of increasing prejudice and suspicion.

The Bolshevik Revolution of October 1917, a bloodless coup, not only made the utopian ideal of a global revolution appear possible, but also held out a brief hope that the Tsar’s antisemitic regime would be swept away and freedom would come to the world’s largest Jewish community. Some Americans, both Jews and non-Jews, saw this as an exhilarating opportunity while others viewed it as a terrifying danger. Socialism’s advocacy of civil rights and tolerance of ethnic and racial minorities appealed to Jews. At the same time, the Bolshevik Revolution prompted “red scares” and unleashed forces of intolerance toward immigrants and minority groups across the globe, and particularly in the U.S.

ImageLike many ethnic Americans, Jews hoped the war would bring liberation to their brethren abroad. Issued by Britain on November 2, 1917, the Balfour Declaration announced Britain’s favorable view of a Jewish home in Palestine. It recognized Jewish nationalism (Zionism) as a legitimate political movement, although it did little to address competing Arab and Jewish claims to the land. The ensuing pattern of contradictions and deceptions on the part of European powers seeking to retain their colonial empires, and Britain in particular, has been interpreted in many different ways during the last century. But it is clear that Arabs and Jews became embroiled in a chronic state of conflict over territory in the Middle East. In the U.S., leaders like Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis voiced support for Zionism, declaring that “there is no inconsistency between loyalty to America and loyalty to Jewry,” while others expressed ambivalence over what it meant to support a nationalist project outside of the U.S. Moreover, the Balfour Declaration had influence outside the Jewish community, capturing the attention of African American nationalist Marcus Garvey, who saw in Zionism a model for black nationalism.

These three events, the reactions that they triggered, and the conflicts they engendered set the stage for American policies throughout the 20th century and into the present. Beginning with the Immigration Act of 1917, the American government adopted increasingly strict laws limiting who could enter the country. This culminated with the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924, which imposed strict immigration quotas and ended a remarkable period of immigration in American history. This legislation, coupled with intolerance of foreigners and rising antisemitism, changed America’s relationship with the world and severely hampered Jews’ efforts to escape Nazi Germany little more than a decade later.

For more information and a list of complementary public programs, visit here.