The Fall of Rome was an arduous, drawn-out process, lasting centuries in the West to over a thousand years in the East. The so-called “barbarians” are often considered a main factor in the fall of the Western Empire and the weakening of the East.

By the 4th century CE, the Romans had a lot of experience with barbarian confederations, opting to fight, recruit, settle or pay off tribes as they saw fit. For the Eastern Romans in the late 4th century, they had to decide what to do with the large Gothic horde at the banks of the Danube.

This was not the first interaction between the Romans and the Goths, as the Goths had rampaged through Thrace a little over a hundred years before Adrianople and actually killed the co-Emperors Decius and Herennius Etruscus at the disastrous battle of Abritus, though this was during a period of instability in the whole empire and there was a recovery before the next major Gothic interaction.

The Goths were culturally and linguistically Germanic, supposedly migrating from Scandinavia then occupying areas around Crimea and the Black Sea. In the mid and late 4th century they were under heavy pressure by the Huns and sought safety across the Danube within the Empire. The Eastern Emperor Valens agreed and planned to use the large force to supply troops, as he was currently embroiled in a tightly contested war against the Sassanid Empire on the eastern borders.

Once in Roman territory, the Goths were cruelly treated by the local officials. Food was withheld or sold at absurdly high prices, there were instances of stray dogs being rounded up by the Romans and sold for the price of one dog per child given up for slavery. The Romans did face an overall food shortage due to the influx of Goths, but the treatment of the Goths was intentionally cruel.

When the Roman officials heard of an impending rebellion they invited the Gothic leaders for a feast and attempted to kill them all. The assassinations did not go well and men on both sides were killed as a few Gothic leaders got away and organized a mass rebellion. Soon after they defeated the local Roman garrison army and armed themselves with captured Roman equipment and seized what food they wanted.

The Goths, actually two main large tribes, the Thervings and Greutungs, were much larger than many of the smaller bands that skirmished on the borders of the Empire and required a large mobilization to be dealt with. Their ranks also swelled with nearby tribes, escaped slaves and prisoners. Valens quickly organized a peace with the Sassanid Empire while heading to Constantinople to raise a larger army and received word that the Western Roman Emperor and Valens’ nephew, Gratian, would send an army as well.

Over the next two years, a few skirmishes and inconclusive battles occurred until Valens had his army assembled, some being newly raised and some coming from eastern territories. The Roman general Sebastianus had scored a number of small victories on the widely dispersed warbands, which caused the Gothic leader Fritigern to consolidate his forces.

Valens was eager for his glory, for his lesser generals and his younger nephew both had a great deal of glory, so when he got word that the Gothic army was moving south to Adrianople, and that they numbered only 10,000 men, he decided to cut off their advance and force a decisive battle rather than wait for Gratian’s reinforcements.

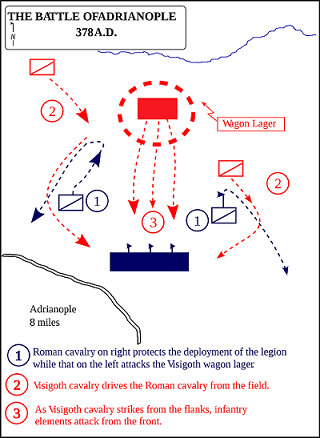

Valens had an army anywhere from 15-30,000, but he was woefully misinformed about the size of the Gothic army; they had about as many soldiers as the Romans and likely more. Though on the day of battle, august 9th 378, the Goths were without a majority of their cavalry, who were out foraging. Valens ordered his men to line up and march towards the fortified wagon camp of the Goths but was stalled when Fritigern sent envoys for peace talks.

This delay allowed Fritigern to send for his cavalry to return to camp while the Romans were forced to wait in the hot summer sun after marching without rest to get to the site. The Goths even fed their fires to send smoke wafting to the already parched Romans. At some point during the negotiations, some of the Roman cavalry attacked and sparked fighting all along the lines.

The light cavalry, particularly on the left flank, were quickly routed, though the Infantry battle was closely contested. The Roman infantry on the left flank pushed all the way to the wagon camp before the foraging cavalry returned. It is unclear how exactly the cavalry attacked, they may have separated and spread around each Roman flank, or they hit hard on the winning Roman left flank.

Either way, the previously successful Roman left was so compressed by this charge that they had no room to fight effectively. Smoke from the fires obscured views and arrows fired from the camp could not be seen to be defended against as they tore into the densely packed Romans. Along the rest of the line, the less experienced men fled while the more elite troops held their ground, but were ultimately overwhelmed.

Emperor Valens may have either taken a fatal arrow shot, or he was wounded and taken to a farmhouse. When the Goths could not force their way in through the guard they reportedly burned down the house, unaware that the Emperor was inside. Aside from the emperor, many skilled officers were killed as well, including Sebastianus, the only general who had had success against the Goths. Sources say that over half of the army was lost, and since the elite troops held the longest, they accounted for the majority of the losses.

The defeat crippled Roman power in the region and The Goths marched on Adrianople and even on Constantinople, but proved ineffective in an assault and simply ravaged the countryside. The Goths dispersed and were eventually pushed back across the Danube.

The Eastern Roman Empire was able to recover and so the defeat did not directly lead to a decline for the East or West, but it set a notable precedent that the Barbarians could fight and win. Previously the power of Rome was too paramount to think of invading with much hope, but only a few decades after Adrianople, a branch of the Goths known as Visigoths sacked Rome.

By William McLaughlin for War History Online