Even though more than 600 prisoners participated in the building of tunnels, only 200 were to take part in the escape.

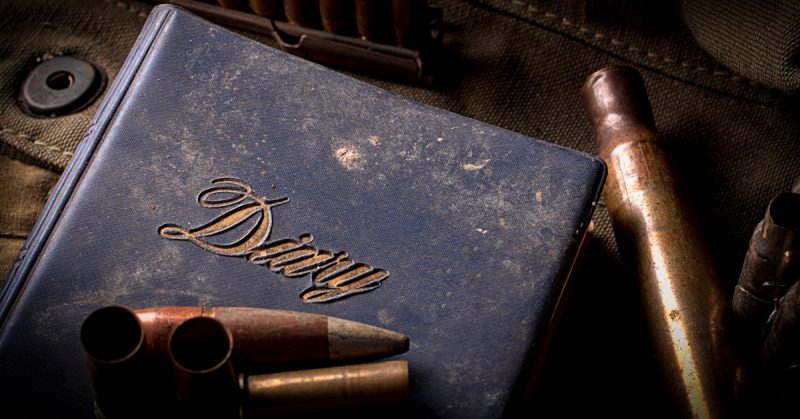

On March 22, 2019, Hansons Auctioneers organized an auction for an item that caused a lot of interest among British collectors. It was the diary of World War Two Royal Air Force Flight Lieutenant Vivian Phillips who was known as one of the organizers of the escape from the German POW camp Stalag III.

The auction was set just two days before the 75th anniversary of the escape of Allied airmen from the camp in Eastern Germany. The historic event that took place on March 24, 1944, became famous worldwide after it was depicted in the Hollywood movie The Great Escape.

A diary that has been described as absolute gold dust was unveiled earlier this year. It was put up for auction by Vivian’s nephew Mark Phillips, 59, along with his uncle’s war medals. The diary is regarded as incredibly valuable since it’s rare for a war diary to have survived the harsh rules of German POW camps.

From Amsterdam to Sagan

Vivian Phillips came from the small village of Hook in the Welsh county of Pembrokeshire. He joined the Royal Air Force in early 1930s. His participation in the war ended in 1943 when he got captured during Operation Ramrod 16, an air raid against the Amsterdam power station Hemweg.

On May 3, 1943, eleven Ventura bombers flew to the Netherlands, but only one reached the intended target. Phillips was the navigator of that last Ventura. They managed to drop the bombs but got hit in the process. Both the pilot, Trent, and Phillips managed to bail out by parachuting.

As soon as he landed, Phillips got into trouble. His parachute dragged him through barbed wire until he was saved by a Dutch patriot. Unfortunately, both of them were captured by a German sailor who arrived at the scene. The two men were taken to an Amsterdam jail. From there, Phillips was moved to Cologne and then on to the German camp in Sagan.

Stalag III

Stalag Luft III in Sagan was a Luftwaffe’s prison camp reserved for captured Allied airmen. It was notoriously very difficult to escape from. It was built on sandy soil that was very unsuitable for digging escape tunnels. The camp also had a system of seismographs responsible for detecting sounds below the ground.

Ironically, despite its reputation, the camp became famous for two escape attempts. One from October 1943 and another from March 1944 in which Vivian Phillips participated.

Both attempts were depicted in movies. The first one formed part of the 1950 movie The Wooden Horse, and the second one was featured in the epic war movie The Great Escape.

Life of a POW

By the end of 1943, Phillips was brought to Stalag III. That was where he started to write his diary. Phillips described the everyday life of prisoners. Short stories about how they were spending their spare time, about the food they ate, and other day-to-day activities are supplemented with sketches and cartoons.

The diary even describes how prisoners smuggled in sugar and fruits to make their own alcohol.

However, the most interesting part of the diary is the section which describes the preparations for the escape. Phillips described the entire process of digging tunnels as well as his role in the venture.

“My role in the tunnel was varied. I began as a member of a group of fellows who played for hours and hours with a medicine ball… At odd times we were joined by fellows who played for a little while and then departed. These fellows were dispersers and in place of pockets they carried two small bags – one either side inside their trousers – supported by a string around their necks.

“By putting their hands in their support pockets they were able to pull a string which acted as a quick release… It was our job to ‘work in’ the light-colored sand from underground to the drab colored sand of the surface.

“All this was done under the very noses of the guards.

“From this I graduated to a kind of foreman. I had charge of a gang of eight fellows whose job it was to pretend to be lolling about lying on great coats. In reality they were digging holes in preparation for their disperser.”

The Great Escape

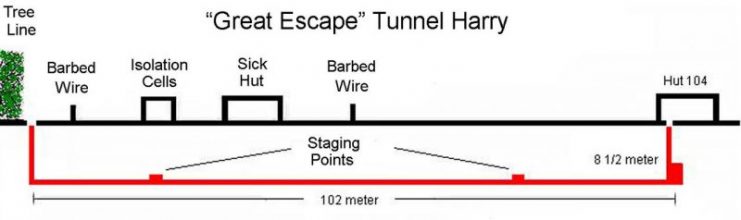

Prisoners were actually digging three different tunnels. These were codenamed Tom, Dick, and Harry in order to keep them a secret from the German guards. The tunnels were very narrow and very deep – some 30ft below the surface. They had wooden supports, electric lighting, and even air ducts.

By January 1944, only Harry was left in effect. Work on Dick was abandoned while Tom had been discovered by Germans. At the beginning of 1944, the Gestapo made a visit to camp with orders to detect all escape routes. The prisoners decided that it was time to act.

As soon as Harry was finished in March 1944, the escape was set for March 24. Even though more than 600 prisoners participated in the building of tunnels, only 200 were to take part in the escape. There was one group of 100 prisoners who had a secure place in the escape group. Another 100 were chosen by drawing lots. Phillips was not among them.

As it turned out, this was a stroke of luck for him. Out of the 200 planned escapees, only 76 prisoners managed to escape. Of that number, all but three were captured within a few days. By Hitler’s personal orders, 50 of them were executed as a sign of punishment.

Phillips and the rest of prisoners had no choice but to wait until 1945 for liberation. He later described the escape attempt as futile: “It is funny how at first one is obsessed by thoughts of escape… later, when one is more settled and able to reflect in a clearer manner, it became obvious how utterly futile these plans would have been.”

Diary stays at home

Vivian Phillips died in 1997 and left his diary to his sole inheritor, nephew Mark Phillips. Not having anyone to pass the diary on to, Mark decided to put in an auction. The diary was bought by a UK collector for the sum of £13,500 ($17,835).

The diary will remain in the United Kingdom, where it belongs. It’s a monument to the vigorous spirit of British soldiers during World War Two.