‘From 1915 the word ANZACs was applied to military formations – at first ANZAC meant a man who had served on Gallipoli, and later acquired broader applications. It generated many slang terms in the first Australian Imperial Force and has become a part of the Australian language’ – the term ‘ANZACs’ (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) represents so much more than the army group; it represents a new nation emerging into the 20th century and beyond.

After losing thousands of men and fighting thousands of miles away from home as part of the British Empire (an Empire in which Australia arguably did not hold any power or political independence) it is important to understand how the ANZAC’s helped to shape Australian national identity and create the legend which is still celebrated today.

Spiralling Events

In the late summer of 1914 WWI commenced, spiralling out of control, and due to an un-necessary web of political entanglement the number of countries who rose in arms propagated. Countries declaring war joined one of two sides (One formally known as ‘The Allies’ and the other formally known as ‘The Central Powers’). Modern machinery and weaponry rather than politics would dominate this new war. However, outdated contractual and political agreements still remained, whereby if certain nations were invaded or entered into war, then so too did another to support its allies, such as Britain, and therefore Australia. Other nations such as France and Russia held similar pacts also committing them to war, known today as the ‘entangling alliances’.

With the British Empire entering the war, all of the countries within the British Empire also declared war ready to engage in battles across the world. Men from all races and nationalities rose up for the cause and fought gallant, heroic battles which changed their nations, their people, the world and the British Empire forever. India, Canada, South Africa, Ireland, New Zealand and Australia amongst others formed their armies and called up young men ready to fight for their personal freedom and to protect the Empire.

The Battle for Gallipoli

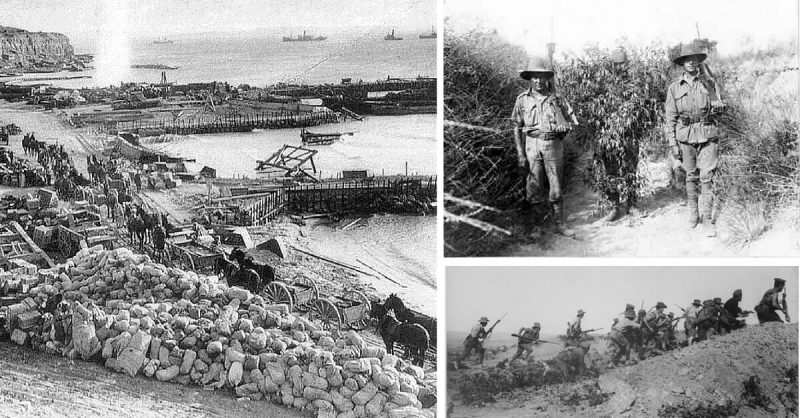

400,000 Australian men volunteered to fight for the Empire. Of this, 60,000 died and 156,000 were wounded, gassed or taken prisoner. Many of these deaths came in the battle of Gallipoli, arguably the place where the ANZAC legend was created. On 25 April 1915 members of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) landed at Gallipoli together with troops from New Zealand, Britain, and France. The objective was to secure the peninsula and relieve their Russian allies to the east, but this began a bloody and gruesome failed campaign that ended with the evacuation of troops on 19-20 December 1915. Varying objectives could not be met and seven months of solid fighting ended in defeat and thousands of British, French, Australian and New Zealand deaths.

The Gallipoli battle itself started with seaborne invasions with three attacks. The British and French attacked the most southern peninsula of Gallipoli. Their advance was minimal as they were pinned down on the beaches and coastal hills struggling to move forward. Further north on the westerly coast of Gallipoli the Australian and New Zealand troops landed with slightly better success, but again they were pinned down by the Turks in various coves and offshore hills. To the Ottoman Empire, ‘The Turks’, the battle was make or break, they needed to repel the allies and to protect their western shores so close to their capital of Constantinople (modern day Istanbul).

The initial attacks were disastrous for the Allies – British plans proved ineffective as they sent more and more ANZAC’s into battle. This led to a long drawn out battle, synonymous with WWI. As the British and French could not advance north they left the ANZAC force to endure the worst in the most reinforced area of the island. This abandonment and failure of British plans would never be forgotten by the Australian people as their men died in great numbers. The battle raged for months with little to no advances from the Allies and strong defensive fighting from the Turks, with the British plan to link all three fighting forces not achieved. Even as small advancements were made, the Turks snuck in and took their positions back under moonlight – months of arduous fighting achieved nothing. The ANZAC men started to feel betrayed; they felt they had no support, and they were right.

British Command: Gallipoli and WWI

Throughout the Gallipoli campaign and generally in WWI, British commanders typically held the higher positions within military ranks and dictated where and how the colonised nations would fight. So when considering how WWI shaped Australian national identity, one of the most important observations is that perhaps these controlling British commanders – commanders that dictated ANZAC fighting which often lead to many deaths – were a main reason for Australians to set themselves apart and to move towards independence in future wars.

An ironic illustration of this is early war propaganda which encouraged Empire troops to fight. One poster from the British government, issued in 1914, read ‘The Empire needs men! Australia, India, Canada, New Zealand, All answer the call. Helped by the Young Lions, the Old lion defies its foes. Enlist now’. The British Empire called for its ‘young lions’, and symbolic propaganda such as this, a poster showing a strong lion standing tall on the highest rock (symbolic of Britain’s power, dominance and strength) with four smaller lions standing closely behind and below (the Allies), was used throughout the Empire, perhaps to show the power Britain held within the world and within its Empire, but also to show importance of countries such as Australia, who were to play a vital role in the war.

This relationship between Britain at the top and Empirical nations proved problematic. Throughout the Gallipoli campaign, to many Australians it seemed they had been sent to their deaths for a piece of pointless land, in an unnecessary war for the British. Feelings and concerns grew ideologically as the battle took more Australian men – meanwhile the stories of war heroics told about even the most insignificant victory continued to grow and be spread throughout communities back in Australia, but with less belief and trust from the people who were beginning to understand the truth.

The feeling of distrust toward the British and the ever-mounting feeling of Australia for Australia grew. The two ideals gathered more pace as the months dragged on. This feeling gained political and official backing as further battles throughout WWI reinforced and highlighted the problems. In WWII this same precedent of British commanders ruling Australian men into battle was not applied; Australians gained more power and fought independently and successfully under Australian commanders alongside, rather than under, their American and British allies throughout the Pacific and Europe. Stories such as the ANZACs at Gallipoli were remembered to prevent falling back into similar circumstances, helping to secure their new path towards a stronger Australian army, and Australian mentality which would return to the mainland as Australian sentiment grew further from that of the British Empire, making the ANZAC legend about more than the soldiers.

Failure to Adapt

One of the main issues within British allied battle strategy in WWI and that of the British high command was the arrogance of the older, experienced members of the British army, highlighted at Gallipoli. Previous wars had been fought using cavalry charges and rushes, but as WWI became a modern war – a war of gas, trenches, machine guns and shelling – new techniques needed to be explored.

However many of the British high command were unwilling to change methods and ultimately they sent wave after wave of men over the top of the trenches in outdated charges against machine guns and highly trained rifleman – many of these men were Australians. Meanwhile, the Germans (as part of the ‘Central Powers’) learned to adapt from day one of the war. The first waves of German men in Belgium walked in battle formation to their deaths – immediately the German commanders changed their methods and the men began to spread out, run, duck and dive, which proved more successful.

The British were repelled and thus began the great retreat across Belgium, however the British rarely altered their fighting methods. Until the very end of the war charges over the top remained in battle formation (mostly men were ordered to walk towards the enemy). It was not until the British upheaval of high command, seeing younger, more inept commanders, that change of tactics occurred, including the invention of the tank and first use in the battle of the Somme, rolling barrages, attempts at numerous deception plans and operations such as tunnelling under enemy positions (to lay bombs which exploded prior to charges). The Australian and other men throughout the empire therefore lost their lives due to badly judged tactics by the British, which pushed the resentment and distrust further throughout the Empire, including in Australia.

Eventually the war was won by the allies and concluded through the Versailles treaty, but feelings and ideologies that grew within the war could not be changed and the minds of nations through the Empire, including Australia had been altered forever. The feeling of cynicism and resentment due to the lack of ability to adapt, the propulsion of troops into hopeless battles, and the high death toll created ideological transformation en masse. Growing national identities and ideas of independence, distrust for the Empire, distrust of British high command and a stronger look to the future shaped countries such as Australia that were firmly cemented in the minds of the people.

The ANZAC Soldier

Negative ideologies were forged throughout Australia due to the reasons previously discussed, but so too were positive ones in part. ANZAC soldiers refer to the term of ‘mate-ship’ – a new respect for one another and a strong sense of brotherhood and a strength drawn from comradeship forged from months of fighting side by side in harsh conditions.

This new view of what an Australian man could be was taken home and communities absorbed and copied this culture, furthering a new national identity and unifying the young nation ideologically. The nation grew stronger with communities coming together as the friendships of soldiers built bridges. As families in Australia lost their sons, fathers and brothers, they leaned upon those in their community and due to this the nation grieved as one and again were brought closer together.

The personal and national need to glorify soldiers and Australians in general helped to mask the grievous nature of loss. But perhaps this loss, this war, was one of the first pivotal wars for the Australians, and moreover a war Australia may have in a sense needed in order to realize the true identity of their nation – to discover their nation, the ANZAC men and their people were stronger than previously thought, more resilient than they had ever been and able to work as one across the country.

Conclusion: Looking to the Future

WWI was a torrid time for ANZAC soldiers. The Gallipoli campaign itself was not tactically successful, however many Australians still see positive aspects. Although many thousands died, the stories of bravery, courage and comradeship (mate-ship) united ANZAC soldiers and Australians creating a new conceptual view. This new view, alongside the growing resentment for the British commanders and politicians throwing Australian men into ‘their war’ arguably created a positive ideology that emerged through the Gallipoli campaign and long after.

This positivity is still seen and promoted throughout Australia through the majority of mediums, including war monuments, television programmes, documentaries, websites and museums. Most specifically, the majority of monuments and museums are dedicated to ANZAC soldiers at Gallipoli. Gallipoli and the ANZAC legend therefore has become folklore within Australian memory and the people honour the brave soldiers that fought and sacrificed themselves for Australia. Gallipoli was not the only important battle for the ANZAC’s, however it symbolises the ANZAC war effort as a whole.

In 2005, Prime Minister Hon John Howard gave a speech at the ANZAC day dawn service, ‘Ninety years ago, the first sons of a young nation assailed these shores, these young Australians, with their New Zealand comrades, had come to do their bit in a maelstrom not their making,’ Still the emphasis remains true to their ideological start of a new nation, it is also emphasises that they were fighting a war which they did not start and as their position was in the Empire, it seems they had no choice but to enter, fight and die.

Australians generally encouraged the outbreak of war in 1914 throughout the nation; however, they did not imagine that they would lose 60,000 of their men. Regardless of this, as the Australian people suffered losses, they did so together, as the whole nation they entered a state of total war and arguably came out stronger, as one. Some may argue WWI was an unnecessary and pointless war, but to Australians it changed so much and perhaps it was a necessary testament to the strong nation they were, and which helped them to move toward the solid position they hold within world order today.

About the Author

My name is David J. Armstrong (BA Hons) and I am a British military historian from Buckinghamshire. I graduated from university with a degree in War & Conflict in 2014. Since then I have been writing my first non-fiction book about ‘D-Day’ along with other short pieces as found on my blog. I will be attending university again in 2016 and studying towards my MA Degree in Military History with the hope of continuing on to my PhD in the same subject thereafter.

I love to research, learn and write about history. My specialist subjects and my real passions are the wars of the 20th century including WWI and WWII. You can find me as part of various historical associations such as the Historical Writers Association and you can also find me on twitter as @djahistory.

On my blog you will find a collection of work – things that I am working on (such as articles and reviews, historical volunteer work and articles for online sites and magazines), things that I have done in the past and things that generally interest me within history (Including historical sites and museums I visit, books I read and articles I am intrigued by).

Please feel free to comment on my blog posts and follow me. I hope you enjoy my work.