On January 28, 2014, the Medical Press ran a story that linked Agent Orange to skin cancer.

Veterans of the Vietnam War who may have been exposed to the herbicide, Agent Orange, could be at a higher risk of different types of skin cancer. This information comes from the February issue of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery which is the official medical journal for the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS).

The recent study adds to previous evidence that risk of non-melanotic invasive skin cancer (NMISC) is increased, even after four decades after the initial Agent Orange exposure. Some exposed veterans have unusually aggressive non-melanoma skin cancers. Dr. Mark W. Clemens is the lead author of the study and is an ASPS Member Surgeon.

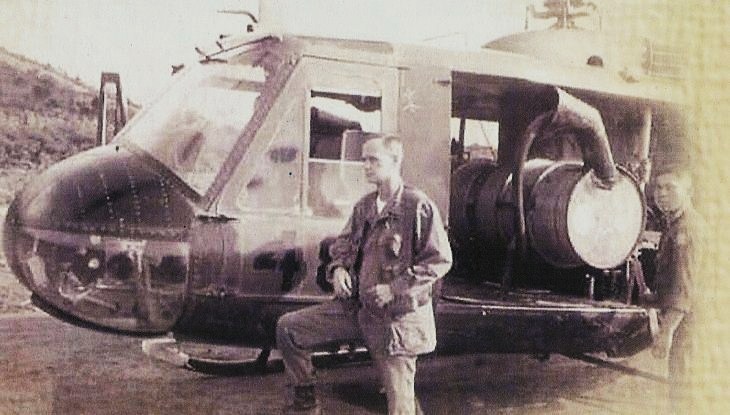

At the time of the Vietnam War, Agent Orange was used as an herbicide and a jungle defoliant. The use of this chemical has been linked to a wide range of cancers and other unfortunate diseases which were caused by the toxic dioxin contaminant TCDD. “TCDD is among the most carcinogenic compounds ever to undergo widespread use in the environment,” according to Dr. Clemens and coauthors. Veteran Affairs have recognized and provided benefits for particular cancers and health problems that are associated with dioxin exposure during military service. Unfortunately, skin cancer is not one of those conditions.

Researchers have analyzed medical records for 100 men who have enrolled in the Agent Orange registry at the Veterans Affairs Hospital in Washington, DC between August 2009 and January 2010. Exposure to Agent Orange includes living or working in contaminated areas, which is what happened to 56% of veterans. 30% were actively spraying the herbicide and simply traveling through contaminated areas for 14% of the exposed. This study was conducted to men with light skin tones.

NMISC in TCDD exposed veterans was 51% which is about two times as high as expected for men in a similar age bracket. The risk of skin cancer has increased to a whopping 73% of veterans who have sprayed the chemical. Studies have shown that men with lighter complexions and light eyes are also reportedly to be at a higher risk.

It is said that 43% of veterans have chloracne which is a skin condition due to exposure to dioxins. For this particular group, the rate of NMISC was over 80%. The rate of the most serious forms of skin cancer, malignant melanoma, was similar to men of a similar age. The article includes two case reports of oddly aggressive NMISC—with numerous recurrences that required multiple surgeries—occurring in TCDD-exposed veterans.

Exposure to Agent Orange and TCDD have been linked to a large variety of health problems which also includes many different forms of cancers. The association with the basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma, which are two common forms of skin cancer, are unclear.

The cases of “aggressive and diffuse” non-melanoma skin cancers found in veterans who have been exposed to TCDD were first reported in plastic surgery journals during the mid-80s. Dr. Clemens and his colleagues began their study when they observed similar patients in their clinic over the past few years. The researchers emphasized that their study has some very important limitations; which include the lack of detailed information of TCDD exposure and the absence of a comparison group of Vietnam-era veterans who were not exposed to Agent Orange.

The results strengthened the previous reports associated between TCDD exposure and the development of MNISC, even after so many years have passed since the exposure. Certain groups seem to be at a higher risk, which include veterans who were actively involved in spraying the chemical, those with chloracne, and those with lighter complexions. Dr. Clemens and coauthors write: “Further studies are warranted to determine the relative risk within this patient population and to determine appropriate management strategies so that veterans may receive the care they earned in service.”