Alexander’s breathtaking conquest of the Persian Empire in little more than a decade has led two millennia of historians to find a word in any language that exceeds stunning when they look for a way to describe his astonishing series of campaigns. To put the achievements of the young king, his generals, and their mixed Macedonian and Greek army in any context, it is traditional to gift their leader with the simple epitaph “the Great”, making him the first European or Western ruler to be honored in that manner, and the name Alexander the Great has endured unchanged in this form from the hour of his premature death three centuries before the birth of Jesus Christ, right down to the present day.

Knowing the outcome of his great invasion for so long has also had the result that it is sometimes easy to forget how narrow the odds of success were when Alexander crossed the Hellespont with his Companion cavalry in 334 B.C. Though his entire army and navy were said to number perhaps 50,000 men in total, his resources, particularly with regard to ready money for salaries, were dwarfed by the supplies and manpower of his Persian opponents.

Indeed, the Persians had themselves recruited and paid Greek mercenaries to oppose the march of Alexander’s host as it made its way south along the western coast of Anatolia and down into Cilicia. The leader of these mercenaries was Memnon of Rhodes, a general who had married into the Persian nobility and enjoyed a high reputation among Greek and non-Greek alike. Memnon recognized that Alexander had a very limited period in which to keep such a large force in the field, and he pushed his Persian employers to begin what would today be called a scorched earth policy to deny the Macedonian king the benefit of living off the land.

Memnon’s insight at the very outset of Alexander’s campaign meant that he was in a unique position to stymy the mercurial king’s ambitions at their source, effectively strangling them at birth. In addition to forcibly denying the Greek-Macedonian army supplies, he also advocated taking advantage of Alexander’s relative weakness on the sea to launch a Persian counter invasion of southern Greece and stir up cities like Thebes, Athens, and Sparta, former independent powers which harbored considerable resentment at the Macedonian hegemony.

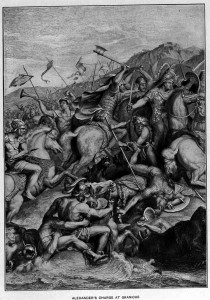

The local Persian commanders overruled Memnon’s counsel, however, most likely because his Greek ethnicity leant his suggestions to burn their land and deplete their garrisons suspicious in the extreme. Instead, they decided to give battle and defeat the upstart Alexander in the open. Memnon was entrusted with leading the Persian forces and his own Greek mercenaries. The two armies met at the Battle of the Granicus River and the issue was very nearly decided by the simplest method possible when Alexander was caught cold leading a charge against the Persian line with a blow to the head and almost knocked from his horse. Only the intercession of Cleitus the Black saved the insensible young monarch’s life. Despite this close call, Alexander’s army carried the day, and the Persians fled the field, leaving the Greek mercenaries who had fought with them to face cold blooded execution at the hands of their fellow countrymen as traitors. Memnon managed to escape in the confusion.

Following the defeat, Memnon commanded the defense of the town of Halicarnassus and by skillful deployment of his forces and a ruse, came close to ending Alexander’s life once more. By sheer weight of numbers the Macedonians prevailed, and Memnon finally received permission to sail to the Greek mainland as he originally planned and campaign there, but just when his strategy was bearing fruit and it appeared that the major Greek cities were about to rise, he was struck down with what was described as a “fever” and died.

Given the nature of the times, poison could not be entirely ruled out, but whatever the cause of death, the Persians and anti-Macedonian Greeks had been dealt a mortal blow. Memnon’s strategies were put on hiatus only to be resumed again once more after Alexander had defeated the Persian King Darius III at the Battle of Issus, but by that time Alexander had advanced so far and his army was so well supplied that he had little need either of the naval forces or tributary payments of the Greek cities.

It is an enduring question as to how the ancient world might have been altered had Memnon not perished in the early days of the war or had his advice been taken up by the Persian powers that be when he had first offered it. Certainly, Alexander’s victory would not nearly have been so swift and total as it subsequently was once he had cleared Anatolia. The conqueror of the known world would never again meet an individual opponent who possessed such an ability as Memnon of Rhodes to stop him in his tracks, or even take everything that he held dear from him, except perhaps himself.

- Image 1, source: Wiki Commons

- Image 2, source: Wiki Commons

- Image 3, source: Wiki Commons

- Image 4, source: Wiki Commons