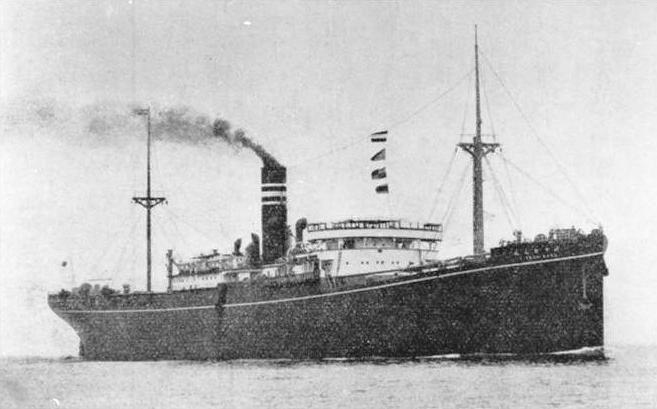

It is inevitable that in war there will be tragedies, but few can match the sheer heartlessness and unnecessary loss of life that occurred with the sinking of the Lisbon Maru on the 1st October 1942, in which almost 1,000 men lost their lives.

Late in September of 1942, the Japanese assembled 1816 British and Canadian prisoners of war on the parade ground of the Shamshuipo Camp in Hong Kong. The prisoners were to be transported to Japan to work as slave labor in the dockyards and ports of Imperial Japan. The men had been captured during the fall of Hong Kong late in 1941 and were hoping for early release, but it quickly became apparent that their release was not imminent and that they would be prisoners for a long time. The news that they were to be transported to Japan did not fill them with enthusiasm even though the conditions in Camp Shamshuipo were appalling with crowded quarters, poor food, non-existing medical supplies and rampant disease. Death was common as the conditions were so bad.

The entire contingent of prisoners, the majority of whom came from the Royal Scots, Middlesex Regiment and Royal Artillery, were under the command of Lt. Col. H.W.M. (Monkey) Stewart, who was the Officer Commanding of the Middlesex Regiment. He was assisted by a small number of fellow officers. The prisoners were divided into groups of 50 men and given a detailed but ineffective medical examination before being transported to the Lisbon Maru on the 27th September. Conditions aboard the freighter were unimaginably bad. All 1816 men were squeezed into three holds aboard the ship. The holds were divided with wooden dividers and men were packed like sardines with a mere 18 inches of space for each person. Those on the lower levels were inundated with human waste as illness and dysentery were rife.

Also, there were 25 Japanese guards and 778 Japanese troops on board the Lisbon Maru when she left Hong Kong.

The food issued to the prisoners was good by prisoner of war standards, and there was fresh water for drinking but none for washing. There were only life belts for half the prisoners and far too few lifeboats. All four of the lifeboats were reserved for the Japanese troops along with four of the six life rafts. This left two life rafts to cater for 1,816 prisoners.

The Lisbon Maru sailed into good weather, and for four days the voyage was very uncomfortable but uneventful, and the prisoners were allowed on deck for some fresh air and exercise, but this changed dramatically early in the morning of the 1st October.

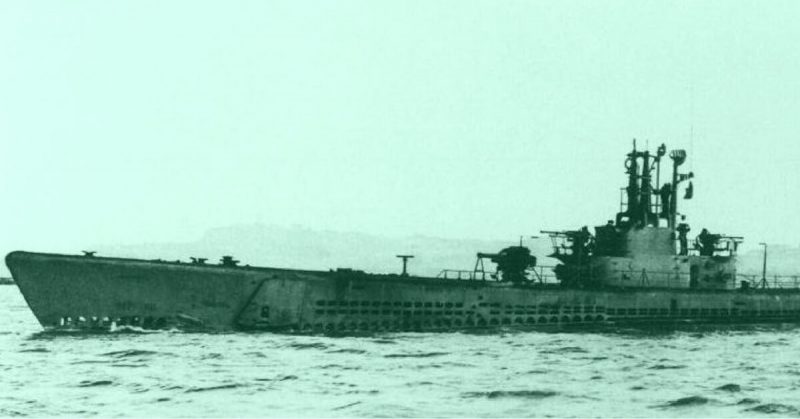

In the evening of the 30th September, the USS Grouper (SS 214), a submarine attached to the US Pacific Fleet, sighted a group of nine sampans and a large freighter in the East China Sea, just south of Shanghai, some six miles off the Zhoushan archipelago. The moon had risen, and the vessels were clearly visible in the bright moonlight, but the moonlight prevented the captain of the submarine from launching an attack immediately. He determined their course and moved ahead of the flotilla intending to launch his attack at daybreak. The captain of the USS Grouper had no idea that the freighter carried prisoners of war, he could only see the Japanese troops.

At 6:30 am on the morning of the 1st October, the prisoner’s duty officer started waking the men to get them ready for roll call at 7:00 am. Some of the men took advantage of the early start to visit the latrines on the deck in an attempt to avoid the inevitable rush a little later on.

At daybreak the submarine was not in a position to fire but by 7:00 am she was ready, and as the Americans only saw the Japanese troops on board, they fired four torpedoes and of the four, one scored a hit. The commander of the submarine then saw that the freighter had changed course and was lying dead in the water. The commander of the submarine reported that the freighter raised a flag that looked like ‘Baker’ and started firing at the submarine with a small caliber weapon.

The prisoners had felt the explosion, and the lights failed, leaving them completely in the dark. The prisoners up on deck saw intense activity amongst the Japanese troops before they were hustled down into the hold but there was no information about what had happened. Shortly before 9:00 am, the Grouper fired another torpedo, but it missed. The Grouper had spotted a bomber in the air around the freighter just before firing the last torpedo, and shortly after the last torpedo was fired, three depth charges went off. The submarine came to periscope depth and saw the plane but not the freighter and assumed, incorrectly, that the ship had sunk. The submarine remained in the area during the day, but at dusk, the commander decided that they should leave while they could.

The Japanese troops on the freighter calmed down but became completely unresponsive to the prisoners. Requests for food, water, latrine breaks or latrine receptacles were ignored, and the conditions in the hold deteriorated.

The prisoners could feel that the freighter was lying dead in the water and had started to list to one side. What they did not know was that the destroyer ‘Kure’ had arrived and in the late afternoon the transfer of the 778 Japanese troops had started. While this transfer was taking place, the Toyokuni Maru arrived, and a conference was held to discuss what was to be done with the Lisbon Maru. The outcome was that the remaining Japanese troops would be transferred to the Toyokuni Maru while the crew of the Lisbon Maru along with the 25 Japanese guards would remain on board the Lisbon Maru while it was towed to shallow water. Lieut. Wada, the leader of the Japanese guards, insisted that the hatches covering the holds be closed as he did not think that there was sufficient manpower to stop the prisoners escaping. The captain of the Lisbon Maru disagreed as the risk was too great if the ship sank but by 9:00 pm that night Lieut. Wada had insisted that the hatches be closed as he was in charge of the prisoners, not the captain of the ship. Reluctantly the captain ordered his crew to close the hatches.

This meant the prisoners were in complete darkness and there was no airflow, so the conditions below deck became impossible. No food, water or latrine breaks had been allowed for over 24 hours, and most of the prisoners had no more water in their bottles. Col. Stewart maintained order and kept morale high by insisting that the Japanese would not abandon ship, leaving the men to die. During the night conditions deteriorated so badly that Col. Stewart decided to try and break out of the hold. One prisoner produced a butcher’s knife and Lieut. H.M. Howell climbed the ladder and tried to pry open the hatch. Unfortunately, he was too debilitated to open the hatch.

Eventually, the prisoners managed to get the hatches open, and there was a state of panic as everyone tried to get up the ladder. Officers maintained order, and soon the men were climbing the ladder one by one only to be met with machine gun fire as they exited the hatch. The Japanese guards were firing on the men as they appeared. After a while, the prisoners managed to subdue the fire, and 1,750 men made it off the Lisbon Maru and into the water. They swam towards the Japanese boats that had come to the aid of the Lisbon Maru but were met with gunfire as Japanese soldiers strafed the water. Some prisoners made it onto the ships but were shot and their bodies were thrown back into the sea.

Some prisoners were picked up and taken to Shanghai, but 338 men were rescued by Chinese fishermen who defied the Japanese and sailed out to collect the swimmers. The fishermen never disclosed that they had rescued the prisoners and today there is a small museum on Dongii island which caters to the rescue. Dongii island was where the prisoners were cared for until the following day the Japanese landed on the island and recaptured all the prisoners.

A roll call showed that 846 men had died in trying to escape the sinking Lisbon Maru. The remaining prisoners ended the war as forced laborers, but many died during the harsh Japanese winters.

At the end of the war, the captain of the Lisbon Maru was sentenced to seven years in prison, the Japanese interpreter, Niimori Genichiro, was sentenced to 15 years in prison but Lieut. Wada Hideo, who ordered the hatches closed and battened down, died before he could be brought to trial.

The wreck of the Lisbon Maru has lain quietly at the bottom of the sea but now researchers indicate that they have located the wreck of the Lisbon Maru lying four miles off the coast of the island of Dongfushan, in some 100 feet of water. A Chinese businessman, Fang Li, commissioned the search saying he wanted to raise the wreck and return the bodies to their families. This has not received a warm reception from the families of the dead men or the survivors. They feel that the wreck should have the status of a war grave and should lie undisturbed.

One of the survivors, 92-year-old Dennis Morley, of Stroud in Gloucestershire remembers the fateful day as if it were yesterday. In an interview with The Telegraph, he described the hellish experience that he and the other prisoners went through but he is thankful that he went on a ‘peace & reconciliation’ trip to Japan in 2007. He believes that this trip brought him peace and put a stop to his nightmares but he has very strong views that the wreck must not be disturbed.

The gallantry and bravery of the men aboard this freighter and the bravery and dedication of the officers that managed the evacuation must stand proudly in the annals of maritime warfare.