There’s an ongoing argument regarding the manufacture and potential use of nuclear weapons. One side sees them as a necessary evil, an unfortunate side effect of living in a world that has been very much forged by conflict, and the other views them and their effects as horrifying and wholly unnecessary, like smashing an ant with a hammer.

Both points of view came to the fore when a museum in Los Alamos, New Mexico, the city famed for being the place where the first atomic weapons were created, put an end to the possibility of a traveling exhibit from Japan being shown there because of its anti-nuclear weapon theme. The Los Alamos Historical Museum refused to host the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum’s traveling exhibit until the conflict over the theme could be otherwise rectified.

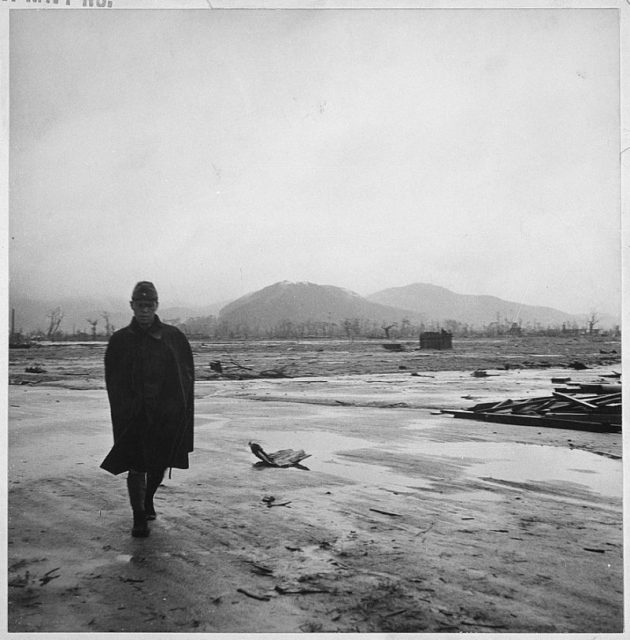

The exhibition intends to draw attention to the horrors of nuclear weapons through exposing the personal effects of victims, like articles of clothing, exposed plates, and other personal items, from both Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The first nuclear weapons were developed in Los Alamos in the 1940s as part of the World War II era Manhattan Project, which enriched uranium for the bomb. Facilities in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and Hanford, Washington, were also involved in the project. The two bombs created in Los Alamos were then dropped on the two Japanese cities, killing 210,000 people, and effectively ending the war.

Given that the New Mexico city is still home to one of the U.S.’s nuclear weapons research centers, the Los Alamos National Laboratory, it is understandable that the museum’s board of directors experienced some discomfort regarding the exhibition’s theme of abolishing nuclear weapons. The exhibition would also be somewhat timely, as the Los Alamos National Lab is in direct competition with the U.S. Energy Department’s Savannah River Site in South Carolina over the production of plutonium pits, the element which is required to trigger nuclear warheads. While no new pits have been dug since 2011, the Energy Department wants to build eighty pits by 2030.

“The Los Alamos Historical Society will continue its dialogue with the museums in Hiroshima and Nagasaki in hopes that we can overcome cultural and linguistic differences and host exhibits that are respectful to all of our communities’ concerns and stories,” Heather McClenahan, executive director of the Los Alamos Historical Museum said. “In other words, we hope this is not the end but the beginning of delving together into our history and the questions it raises.”

The board of the Los Alamos museum turned down the current plan in mid-February, which meant failing to meet a funding deadline required to hold an exhibit in 2019. Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum official Tomonori Nitta said that it’s now the responsibility of the Los Alamos side to come to a resolution, and he hoped the exhibition would still be possible. Even if it wasn’t possible by the proposed date, he expressed a desire to hold an exhibition at an undisclosed later date, and he also hoped that the two museums would cooperate in overcoming obstacles towards holding the collection.

“We only wish people from around the world to see our exhibit and learn the reality of atomic bombings and their consequences,” Takatoshi Hayama, an official at the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum, said.

McClenahan went on to state that neither the museum nor the community was against the idea of the abolition of nuclear weapons, and then qualified that statement by suggesting it required a scientific approach. She also stated that thousands of Los Alamos residents are heavily involved with work on nuclear weapons and related issues, and that includes non-proliferation.

The atomic bombing exhibits have been seen in twelve cities in the United States and will be in Budapest, Hungary, until the end of August before traveling to France and Belgium later on this year.