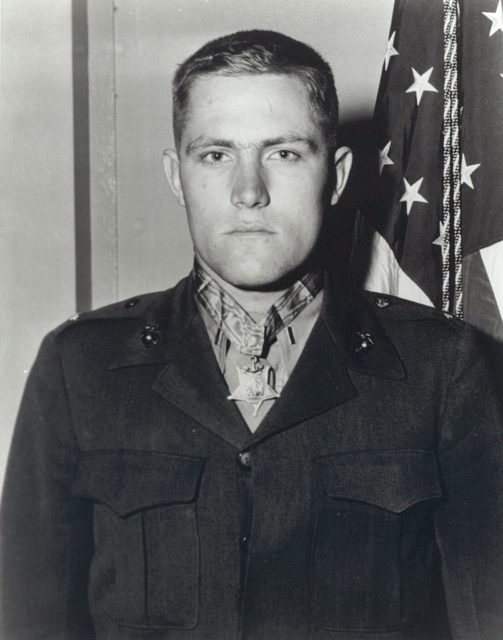

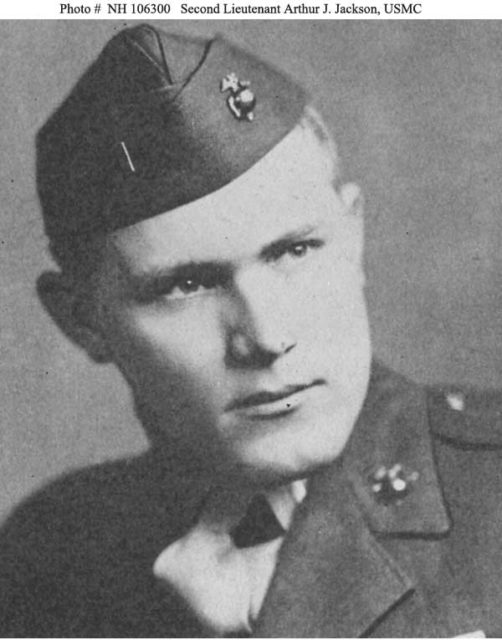

Arthur Jackson enlisted in the US Marine Corps when he was only 18 years old. He quickly became a super soldier, earning both the Purple Heart and the Medal Honor for his service during World War II. He was a career military man, and served at Guantanamo Bay in the early 1960s. It was there he shot and killed a man, claiming the victim was a Communist spy.

Arthur Jackson’s upbringing and early military career

Arthur J. Jackson was born in Ohio, and grew up in both the state and Oregon. After graduating from high school, he moved to Alaska, where he worked for a naval construction company. In 1942, at the age of 18, he enlisted in the Marine Corps.

It didn’t take long for Jackson to become an elite soldier. In January 1944, he participated in Operation Cartwheel, during which he carried a wounded soldier up a steep hill while facing heavy Japanese fire. For this action, he was awarded with a Letter of Commendation.

Next, Jackson took part in the Battle of Peleliu, one of the most deadly Marine Corps campaigns of WWII. During the battle, he ignored enemy fire to attack a pillbox holding 35 Japanese troops. He trapped the soldiers in the installation with automatic weapons fire, before using phosphorous grenades. All 35 inside the pillbox were killed.

Following the battle, Jackson was awarded the Medal of Honor for conspicuous gallantry. He was also presented with the Purple Heart, after suffering injuries during it. Prior to receiving the Medal of Honor, he was sent to Okinawa, where he served as a platoon sergeant with the 1st Marine Division.

Rubén López Sabariego and other Cuban workers at Guantanamo Bay

In 1903, the US took control of Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. Soon after, a naval base was built there. For decades, thousands of Cuban citizens were employed at the base. Even after the Cuban Revolution, many continued to work there with relatively unfettered access.

Rubén López Sabariego was one of those workers. He was born in Cuba and orphaned at an early age. He began working at the base as a carpenter in 1939 and was employed there for six years. In 1949, Sabariego returned to Guantanamo, this time working as a bus driver.

The night of the incident

Much of what happened on September 30, 1961 comes from Lt. William Szili. He and Jackson had been drinking that night, with the lieutenant saying each man had six martinis. Szili then shared that he’d received a call from Jackson later that night, after he’d found Sabariego in a restricted area of the naval base.

It was Jackson’s belief the bus driver was a Communist spy.

When Szili met up with Jackson, he told him that base police had asked them to bring Sabariego to the northeast gate. That was impossible, as a ferry was needed to transfer him and it had already stopped running for the night. The men, instead, decided to take him to a different gate that had been abandoned after the Cuban Revolution.

When they got to the gate, it was padlocked. Jackson asked Szili to find a sledgehammer, so they could break the lock. When he returned, however, Jackson told him he’d been able to get through the lock, after which he was attacked. In the confusion, he’d shot and killed Sabariego.

The cover-up

Jackson told his colleague that he’d thrown Sabariego’s body over a cliff. The next day, the two men took the body to the Cuban side of the beach and buried him. Jackson later decided they should move the body to the American side of the island. The two men enlisted other troops to help them do this.

Georgina Gonzáles, Sabariego’s wife, worried about her husband. She eventually received permission to enter the base and look for him. She was told he’d been shot by Cuban authorities. A week after her final visit to the naval base, her husband’s body was released to her. It was approximately two weeks after the shooting.

Sabariego’s killing was an issue in Cuba and is cited as one of the reasons why the country refused to sign a treaty in 1966.

Aftermath of the incident

Arthur Jackson requested a court-martial from the Marines, so he could clear his name. The request was denied and he left the service in 1962.

Jackson later joined the Army Reserves and remained active until 1984. He also worked for the US Postal Service, and passed away in 2017, at the age of 92.

Szili had a much more difficult time following the shooting. He claimed his name had been unnecessarily besmirched, and, like Jackson, requested a court-martial. This request was denied.