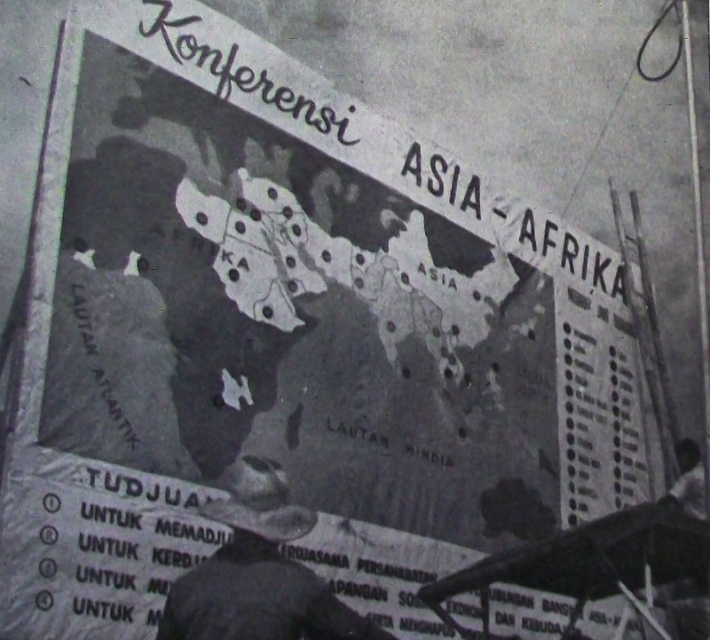

The Bandung Conference of 1955 was a meeting of Asian and African nations, many of which were newly emerging from colonial rule. It was an attempt to add a third force to the international order of the Cold War and to provide a stronger voice for the Third World.

The Bandung Conference was meant to give Third World nations a say in international politics. Unfortunately for the participants in the conference, it didn’t quite work out as planned. And for one of the organizers of the Bandung Conference, it marked the beginning of the end.

The Third World

“Third World” didn’t always have the strong negative connotations it does today. At the outset of the Cold War, French demographer Alfred Sauvy coined the term in his essay “Three Worlds, One Planet.” At that time, it had a wholly different meaning from what we think of today.

In describing the international situation of the post-war era, he divided the main political entities into the First World (NATO countries and their allies), the Second World (Warsaw pact countries and their allies), and the Third World (unaligned countries, or countries that were not involved in the Cold War).

While the term was coined in 1951, the Third World only became more than an abstract entity with the Bandung Conference in 1955. The conference made “Third World” a badge of honor, much to the chagrin of Western nations hoping to have allies in their former colonies.

Leaders of newly emerging democracies and other nations were eager to make their mark, and the Bandung Conference gave them an opportunity to have their voices heard and plan a third way. In doing so, the Bandung Conference earned the ire of both the Eastern and Western Blocs.

The Bandung Conference

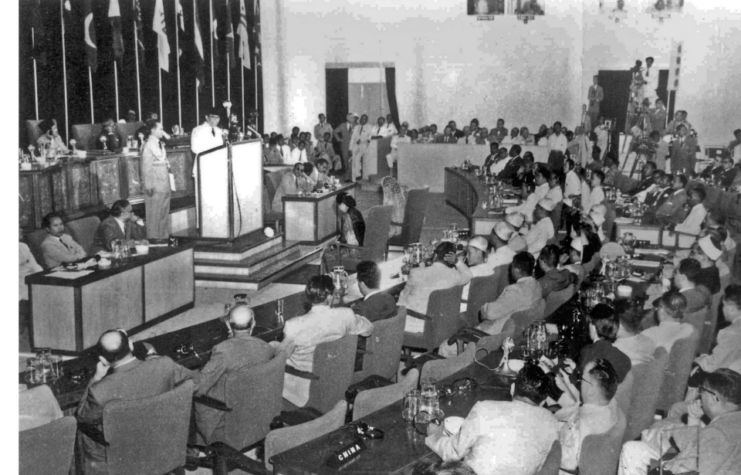

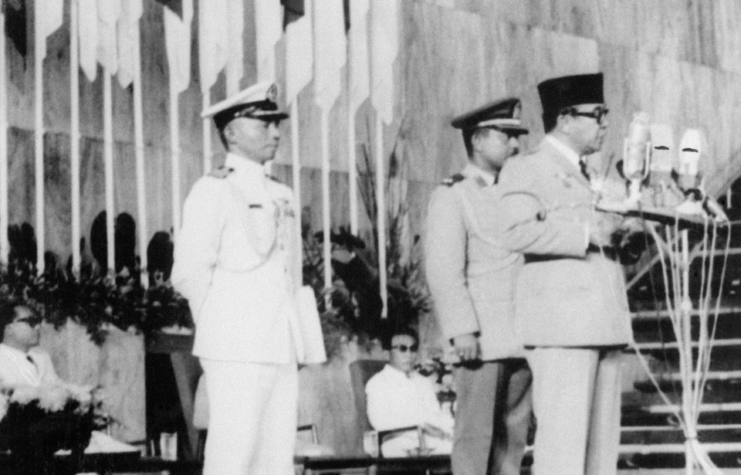

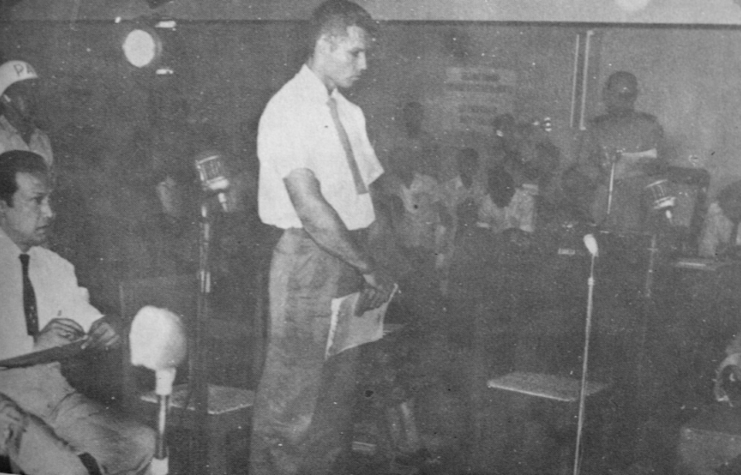

Indonesia’s President Sukarno had the idea to bring together nations that were not officially aligned with either of the Cold War powers. It was a show of international solidarity as much as it was a set of political and economic talks.

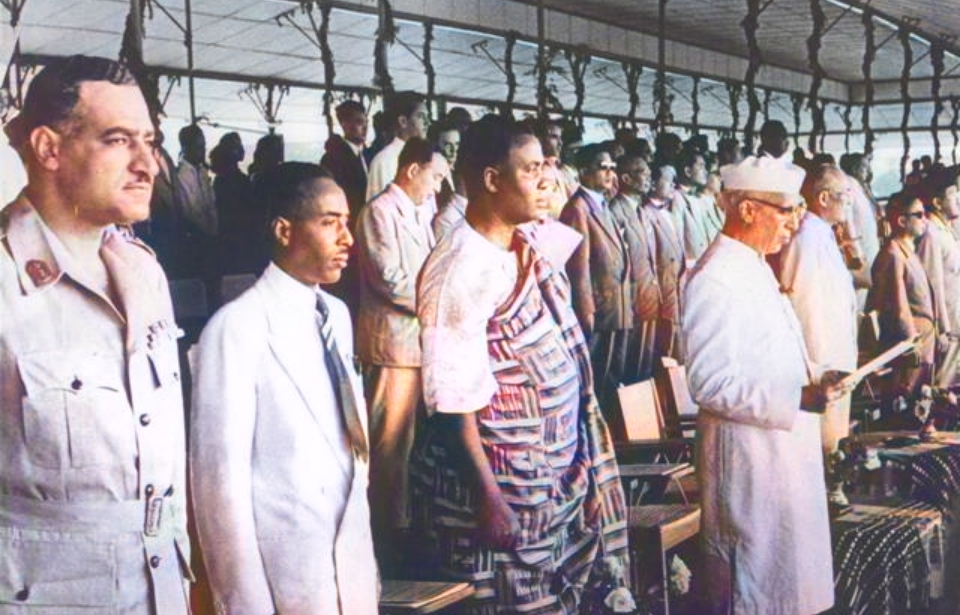

Backed by India’s Jawaharlal Nehru and China’s Mao Zedong (represented at the conference by Zhou Enlai), the conference quickly took shape and gained support from many countries that had formerly been under colonial rule. In all, 29 Asian, Arab, and African states participated in the conference in April of 1955, representing more than half of the world’s population at the time.

The conference didn’t result in any binding legislation, but they did release a set of 10 principles which all participants agreed to — principles devoted to promoting “world peace and cooperation.” The main thrust of the agreement reached by attending nations was a commitment to human rights, justice, sovereignty, and non-intervention. They also committed to settle disputes by peaceful means.

While the conference failed to create world peace, it did improve international cooperation, leading to a second conference in Cairo in 1957, and the establishment of the Non-Aligned Movement in 1961.

The main lasting effect of the Bandung conference was the recognition that many states emerging from colonial rule had common struggles around which they could cooperate. The other lasting effect of the conference was that Indonesia’s President Sukarno became a persona non-grata in the U.S.

Aftermath of the Bandung Conference

In May of 1955, immediately after the Bandung Conference, the CIA received a covert action order from the White House. NSC 5518 worried that Sukarno was flirting with Communism: “The loss of Indonesia to Communist control would have serious consequences for the U.S. and the rest of the free world.”

While Sukarno’s politics were not themselves Communist, he often used populist rhetoric that, in McCarthy-era America, could often be construed as having Communist sympathies. But even neutrality would have been frowned upon. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles had condemned the idea of neutrality in the Cold War as “an immoral and shortsighted conception.”

So it came as no surprise that NSC 5518 authorized various forms of soft-power support for non-Communist elements in Indonesia. The goal was to convince Indonesians that support of the West was in their best interests, not neutrality. The authorization to use “all feasible covert means” to do so came a bit later after the Indonesian Communist Party won 39 seats with 17% of the vote in 1955.

As Vincent Bevins outlines in his book The Jakarta Method, this started a long period of covert intervention in Indonesia, only getting worse as Communist elements gained more popular support in the country.

The interventions went awry in 1958 when an A-26 Invader flown by Allen Lawrence Pope was shot down by an Indonesian-flown P-51 Mustang over Ambon Island. Pope was a CIA agent who was tasked with lending support to anti-Communist Indonesian militants.

Pope was sentenced to death but was released to U.S. custody in 1962 by President Sukarno after a goodwill visit from Robert F. Kennedy. Sukarno’s cooperation with the U.S. on this front did not warm relations between the two countries.

The U.S. still believed Sukarno was harboring Communist sympathies, and the repeated American-backed interference in Indonesia’s internal affairs made Sukarno resentful and suspicious of the U.S. and any aid they might offer.

More from us: Taking K-129: Howard Hughes, the CIA, and the Most Expensive Secret Plot of the Cold War

Eventually, Sukarno was deposed in a complicated military coup that also saw a pogrom against Indonesia’s Communists and anyone suspected of Communist sympathies, and other participants in the Bandung Conference fell to either internal or external pressures, ending hopes for a more prominent international voice for the Third World.