Discrimination was probably not a word you’d hear coming from a commander’s mouth in WWI. In 1914, many of the top brass in the British military were opposed to smaller men joining their ranks, so a height limit was imposed; a minimum of 5’3″ (160cm). If you were shorter than that? Well, you’re out of luck. For a while, at least.

When WWI started in 1914, three-quarters of a million men made their way to recruiting stations all over the UK, which was simply more than the military could process, and a number they didn’t think they’d need. No one expected this honorable skirmish in Europe to turn into a four-year-long slugfest that would need every available man to bring it to its end. Too many men was a problem the British would wish they had later in the war.

WWI minimum height restrictions

Because of the enormous number of surplus men, the British army used minimum height limits that excluded thousands of men from even trying to volunteer; a sneaky way to control the numbers at recruiting stations. They increased the minimum height limit from 5’3″ in August of 1914 to 5’6″ in September of the same year.

The height limit was in place for more practical reasons as well, as back then, men who were shorter were assumed to be physically weak, too.

As the weeks went by, the number of men volunteering to fight had started dropping, so the authorities reduced the minimum height limit to 5’4″ in October, and then back to 5’3″ in November. By July of 1915, volunteer numbers were still in decline, causing the British to further reduce the limit to 5’2″, lower than it was at the start of the war.

Back in 1914, though, the thousands of men who had been turned away from joining the fight for being too short were angry. The government and recruiting stations felt the wrath of these enraged men. One story details an unknown Durham miner who was turned away for being 5’2″, a single inch too short. Every recruiting station he went to turned him down for the same reason. By the later stations, the man was offering to fight anybody who believed being one inch too short made any difference.

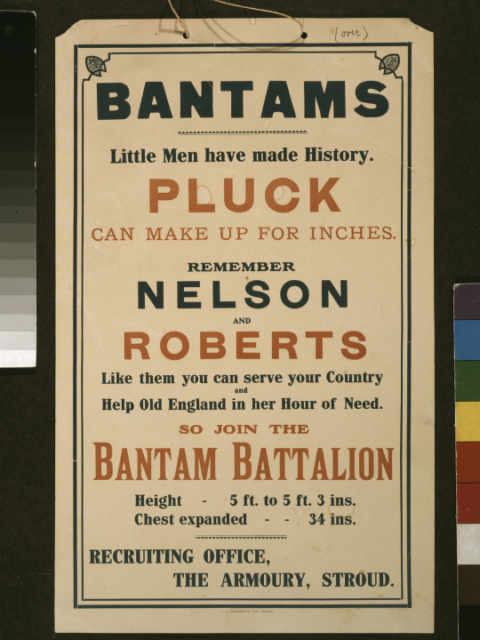

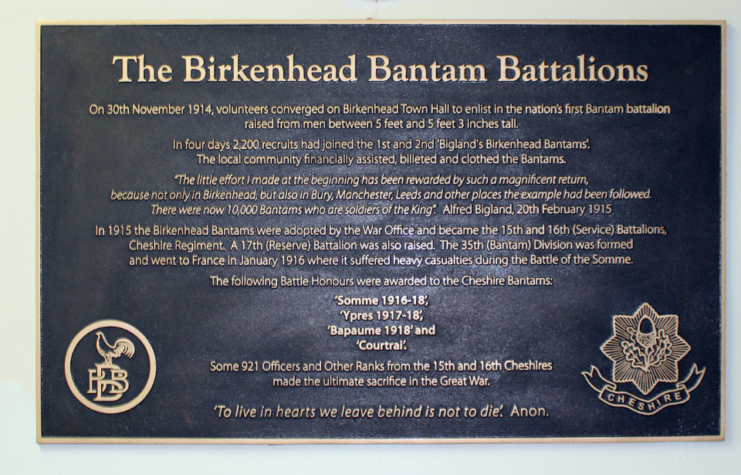

Alfred Bigland, a local MP, came to learn of the man’s struggle, and believed it was ridiculous to turn down men who were shorter, yes, but were certainly not weak or physically unfit to fight. He wrote to the Secretary of State for War, Lord Kitchener, asking to create a military unit for these capable men that had been turned down by recruiters.

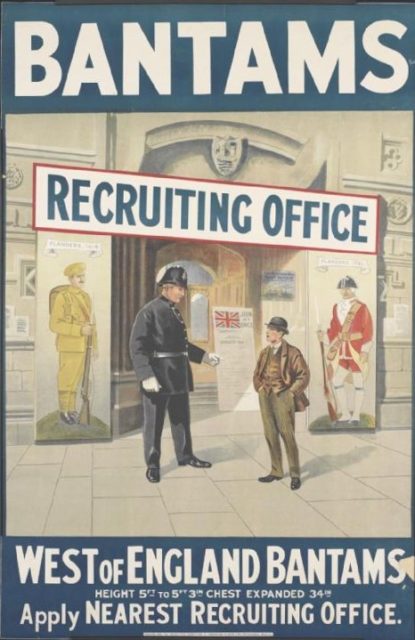

Surprisingly, Bigland’s request was approved. The War Office established battalions for men who were between 5′ and 5’5″ tall. Tens of thousands of smaller men flocked to these units, which were called Bantam battalions. By the war’s end, 29 Bantam battalions had been created, split into three divisions.

Although this allowed thousands of men to join the armed forces, it seems like the easier option would have been simply reducing the height requirements for regular units, instead of creating dedicated battalions for shorter men.

According to Retired Major Andrew Greenwood, it was much simpler, from an administrative standpoint, for the War Office to let towns create their own Bantam battalions rather than incorporating the men into the ranks of the military itself. Additionally, many at the time didn’t foresee the war dragging on and thought the Bantam units would never actually be used.

The Bantam battalions

The men in the Bantam battalions developed a reputation as short, aggressive, and hard men. The War Office had mistakenly assumed that if you were short you were weak. Most of the men in Bantam units had come from a physically tough industry prior to their military service. This made them better than many at dealing with the terrible conditions on the battlefield.

The camaraderie between regular units and the Bantam battalions, and how the smaller men were treated, would be considered condescending and sometimes outright offensive today. A soldier from the Guards Division said: “After we finished telling the Bants they had duck’s disease we had to take a lot of very funny insults in turn. Very sharp tongues they have, and we’ve taken to the little chaps right away.”

Some did not take to the Bantam units, though, seeing them as inferior troops. The physical height difference between the Bantams battalions and “regular” troops could cause problems too, especially when occupying the same living spaces.

A sergeant major in the Northumberland Fusiliers said, “Sir, them bloody little dwarfs have built up the fire steps so they could see over. Now when my lads stand up, half their bodies are above the parapet.”

Like many others on the front lines of WWI, the Bantam units fought hard. They were involved in many of the war’s most brutal battles and lost a large number of men as a consequence. Some Bantam divisions were created entirely from the decimated remains of other divisions.

More from us: Statistician Abraham Wald’s Counterintuitive Insight Saved Lives

As the war dragged on, the army realized there were roles that a man with a shorter stature was particularly suited to, like crewing tanks and digging tunnels. So men who would have previously found themselves in the Bantam battalions were now fighting amongst the ranks of regular troops.

Also, men who were lost from Bantam units weren’t always able to be replaced by shorter men, so taller soldiers began making their way into the Bantam ranks. For these reasons the Bantam battalions slowly transformed into regular units.