It sounded at first like a thunderstorm, distant, rumbling. Then the ground began to shake as grinding columns of tanks and tracked transports finally emerged from the dense woods.

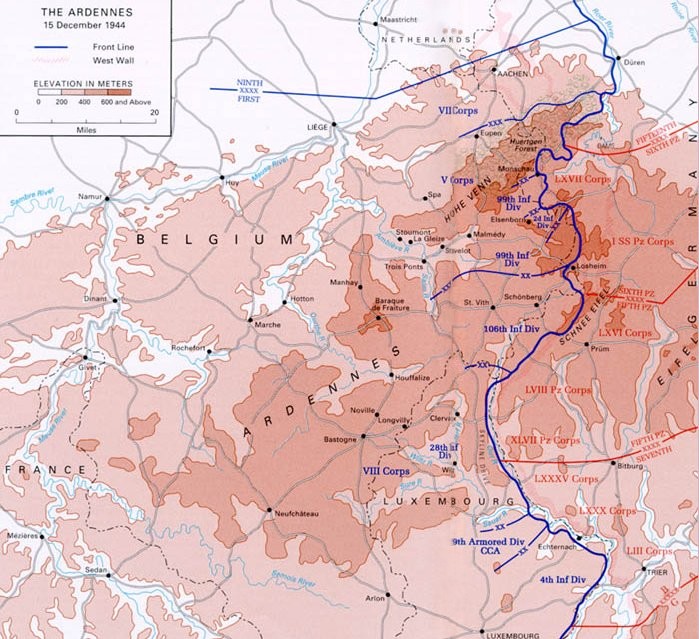

It was December 16, 1944, and what the Germans named operation Watch on the Rhine, and what the Americans would later call the Battle of the Bulge, had just exploded along three roads across an 85-mile front in Belgium’s Ardennes Forest.

Caught by complete surprise, a thin defense of poorly equipped, exhausted Americans was quickly overwhelmed.

Hitler, against his general’s best advice, had ordered the offensive, smashing through the dense woods of the Ardennes, the objective Antwerp, the Allies supply port on the Belgian coast.

His design was to quickly overwhelm the weary American troops and secure the port, cutting the allies off from their line of supply.

That accomplished, he then hoped to end the war on negotiated terms. To accomplish this, the Germans hurled 30 full infantry and armored divisions at the Americans, 200,000 troops, all told.

Twelve elite panzer divisions led the way, instantly heading for the Flemish towns of Houffalize, Sankt Vith, Stavelot, and Bastogne.

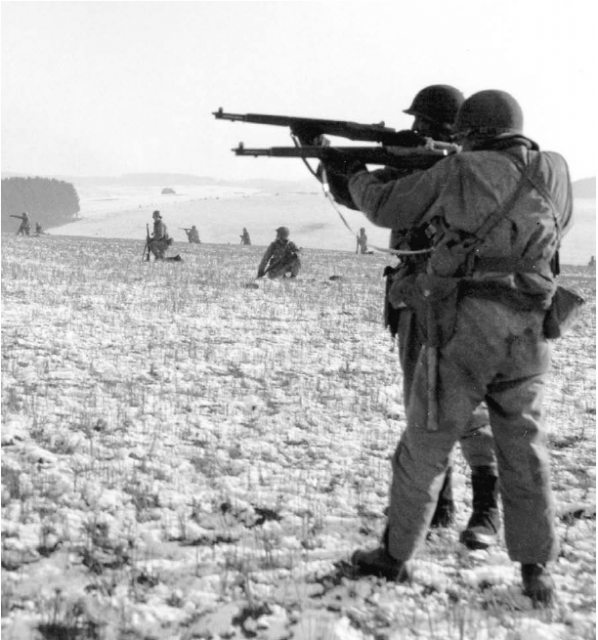

American resistance was at first meager, but intensified as small units recovered and fought furiously, successfully delaying the German advance.

Receiving initial, disturbing reports, General Dwight Eisenhower – Allied Supreme Commander – grasped almost immediately the scale and intention of the German attack and identified the small Belgian village of Bastogne – with its regional network of connecting roads – as the key geographic element.

If the Wehrmacht took Bastogne, they could quickly turn and race toward Antwerp. Three German columns were then advancing on Bastogne, thus small units of American armor, recon, and engineers were dispatched to try and slow the Nazi advance.

Desperate, heroic delaying actions were fought at Noville, Longvilly, and Wardin, blowing bridges, destroying lead tanks, hampering the German juggernaut.

Eisenhower realized it would now be a race between the Americans and Germans to get to, then hold, Bastogne. Unfortunately, he had almost no troops to work with. Casting about, he located the 101st and 82nd Airborne, then resting and refitting at Mourmelon after a long, hard-fought campaign. Unfortunately, they were 107 miles from Bastogne.

Moreover, the cold was then at record lows, intense fog and sleet hindering field operations, making an airborne drop impossible.

Warren Spahn, then a twenty-two year old infantryman serving with the Americans, later a Hall-of-Fame pitcher said, “I was from Buffalo, I thought I knew cold. But I really didn’t know cold until the Battle of the Bulge.”

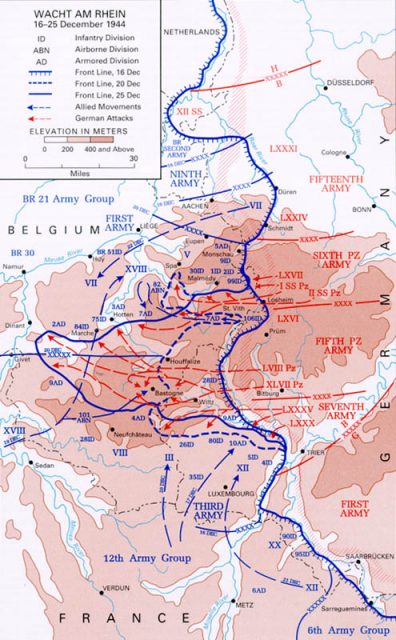

So, the airborne troops were hastily loaded onto an immense convoy, then driven through a night of snow and sleet on treacherous roads to their objectives, the 82nd deployed to Werbomont, the 101st Bastogne. During the afternoon of the 18th, a weary 101st arrived to discover the Germans closing rapidly.

The 101st was then under command of Brigadier General Anthony McAuliffe and, grasping the desperate situation he was in, McAuliffe went straight to work. He sent paratroopers out to reinforce the army units already in the field, trying to slow the German advance.

At Noville, for instance, a team of paratroopers, supported by a unit of self-propelled tank-destroyers, wrecked 17 German tanks in fierce fighting, forcing the Germans to momentarily withdraw.

Despite heroic actions, however, the American forward units were eventually overrun, or recalled to Bastogne as the German assault, seemingly unstoppable, rumbled forward.

As German columns surrounded Bastogne, McAuliffe circled the village with a ring of troops, deploying a hastily configured artillery group in his embattled center.

This deployment bristled with 36 155 mm howitzers, effectively belching-out targeted fire in all directions, blowing apart many German tanks as they approached the American perimeter.

The paratroopers fought furiously, joined now by several additional units, including the all African American 333rd and 969th Field Artillery, making the American compliment at Bastogne the first desegregated unit action since the American Revolution.

Even so, the Americans were still outnumbered 5 to 1, and by late on the 21st short on ammunition, medical supplies, winter-gear, and rations. Indeed, they appeared on the brink of annihilation.

Amazingly, for two days the Germans hesitated, methodically bringing-up reinforcements to make a final, overwhelming push. Eisenhower, however, sensing McAuliffe’s precarious situation, wasted no time. Realizing the German advance had already caused an enormous “bulge” in the American defense, on December 18 he called generals Bradley, Devers, and Patton to an emergency meeting at Verdun.

There it was agreed by all that Patton’s Third Army – then preparing to cross the Saar River and continue east into Germany – would rotate ninety degrees, and race due north – an extraordinary logistical maneuver that in normal times could take days, if not weeks, to accomplish.

Patton, who had sensed the German move weeks prior, had already given instructions for his staff to begin the operation, even before meeting with Eisenhower. By midnight, the 18th, Patton had the 4th Armored Division on the road north, with the 80th and 26th Infantry Divisions stepping-off the following day.

Thus began the second heat of the race to Bastogne, with Patton’s lead tanks still 150 miles south of the Flemish village, “Old Blood and Guts,” typically driving both men and machine as if his life depended upon it.

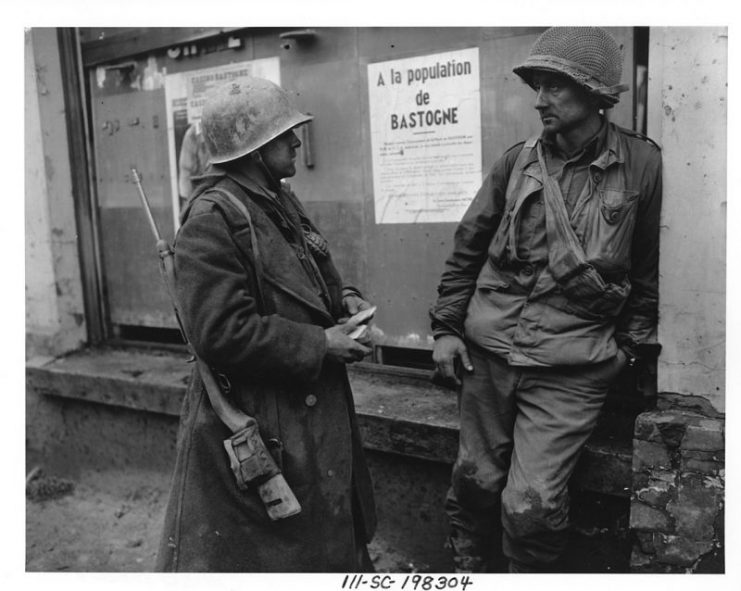

Meanwhile, back at Bastogne, on the 22nd American paratroopers were presented with an unusual sight – four German soldiers approaching under a white flag of truce.

The Germans, it was determined, wanted to present a written ultimatum from General Von Lὓttitz calling upon the Americans to surrender. The note stipulated that McAuliffe had but two hours to ponder his fate, after which the Germans would bury Bastogne under an avalanche of artillery fire.

After reading the note, McAuliffe could barely contain himself. “Nuts!” he fumed. But sensing that blunt message might be interpreted as a bit crude, his written response was lengthened to “To the German Commander: Nuts! From the American Commander.”

Von Lὓttitz, having no idea what the message meant, had it interpreted for him by an American colonel as “Go to the Devil,” which, I suspect, was an exceedingly polite interpretation.

At any rate, the German demand had been a bluff, for they had not the artillery on hand to make good their threat, and besides, on the 23rd the weather cleared. Early that morning the blue skies over Bastogne blossomed with U.S. C-47’s, dropping hundreds of tons of ammunition, food, and medical supplies to the embattled defenders.

Then, screaming in just above the treetops, American P-38 Lightnings and P-47 Thunderbolts appeared, savaging German tanks, convoys, and infantry positions.

The RAF’s Lancaster and Halifax bomber groups added their weight, targeting bridges, rail, and communications, all this giving the desperate ground troops arrayed at Bastogne an enormous emotional lift.

But the clearing weather refroze the slushy ground, making maneuver far easier for the panzers, and the Germans attacked in force, just as sunlight began to fade on the 24th — Christmas Eve.

The blow fell on the south/east portion of the American line. Initially successful, McAuliffe responded by shifting paratroopers, and eventually the Germans were driven back in savage fighting.

Then later that night, German bombers appeared over Bastogne, dropping tons of ordnance, destroying much of the village, but failing to budge the defenders

Come morning, Patton’s divisions were closing on Bastogne, 133,178 vehicles and tanks, grinding through the slosh and mud. As a result, German attacks increased in ferocity, desperate to overwhelm the 101st before Patton could break through. The weather clouded once again but, with reinforcements on the way, the Americans fought back ferociously,

The tip of Patton’s spear was the 37th Tank Battalion, commanded by Lt. Col. Creighton Abrams. They had been fighting through furious German resistance since departing, suffering heavy casualties along the way.

Now closing on Bastogne, the lead Sherman tank, named Cobra King, was commanded by Lt. Charles Boggess. As the 37th headed toward Bastogne they passed through a wild gauntlet of German fire, a scene frighteningly reminiscent of a modern combat videogame.

”We moved full speed, with the other tanks firing left and right,” said Boggess. “We were going through fast, all guns firing, straight up that road to bust through before they had time to get set.” Shells were booming, ricocheting, screeching in numbers too numerous to count.

“I used the 75 like it was a machinegun,” said gunner, Milton Dickerman. Cobra King finally broke through the German gauntlet, and late on the 26th, fell-in with elements of the 101st, two miles from the center of Bastogne. Later McAuliffe drove out and shook hands with Abrams – the siege of Bastogne had been lifted. The desperate race had been won.

The Battle of the Bulge would continue into mid-January, the Germans desperately clinging to what ground they had taken.

But the stunning breakthrough Hitler envisioned never materialized and, over time, massive American reinforcements, air superiority, and German fuel shortages, doomed the Nazi advance, causing Winston Churchill to state: “This is undoubtedly the greatest American battle of the war, and will, I believe be regarded as an ever famous American victory.”

The Battle of the Bulge was the largest engagement ever fought by American forces, but success claimed a heavy toll: 100,000 casualties.

Still, during the one-month period between December 16 and January 16, Allied airpower destroyed 11,378 German transports, 1,101 tanks, 507 locomotives, 6266 railroad cars, and 472 artillery positions, while American ground force inflicted 100,000 casualties of their own, effectively breaking the back of the Wehrmacht. Three months later Adolph Hitler was dead, and his 1,000-year Reich lay in ruins.

By Jim Stempel

For a full list of his current books, please click here: amazon.com/author/jimstempel

Jim Stempel is the author of numerous articles and nine books on American history, spirituality, and warfare. His most recent book, American Hannibal: The Extraordinary Account of Revolutionary War Hero Daniel Morgan at the Battle of Cowpens, is currently available at virtually all online outlets.

Book – “How Easy Company Became a Band of Brothers”

His newest, From Valley Forge to Monmouth: Six Transformative Months of the American Revolution will be released this fall by McFarland, and is currently available for preorder on Amazon.