Crete might be an idyllic tourist island now, but during a 12-day period in May 1941 a mixed force of British, Australian, New Zealand and Greek troops fought like demons to try and repel a German invasion.

When mainland Greece fell to Nazi forces in April 1941, attention quickly turned to securing the territory – which is the largest island in the eastern Mediterranean.

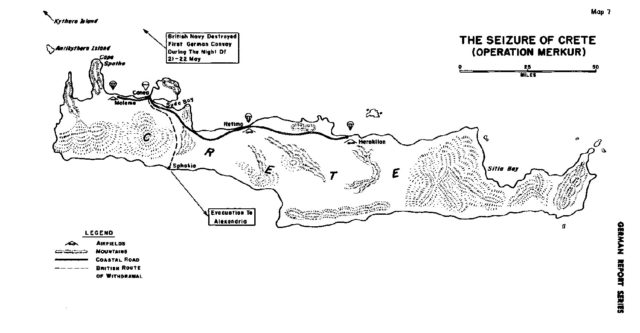

Its central position in the Aegean sea and its harbour at Suda Bay made Crete the ideal place for naval operations. The airfields on Crete were also important as planes based there could hit targets in North Africa, disrupt Nazi oil production in Romania or attack British shipping in the Suez Canal.

The capture of Crete would also stop Allied forces from launching counter-strikes into the newly occupied Balkan region, which the German war machine had trampled through in 1941.

Despite concerns that opening up a new area of conflict would distract from Hitler’s plan to take eastern Europe, he was won over by the Luftwaffe’s plan to use paratroopers to carry out the assault.

The Fuhrer gave his consent for the invasion to go ahead, but with the strict caveat that it must not distract from the invasion of the Soviet Union in any way. German air forces then carried out a bombing campaign on the island, which forced the Royal Air Force (RAF) to evacuate their planes to Egypt.

Thanks to the success of the Allied ULTRA intelligence operation, commander of Crete Lieutenant General Bernard Freyberg was aware of the incoming threat – and as a result, he could plan the defence of the island in advance.

Geography made defending the island a difficult task, as did the poor communications equipment among the fighting forces. The key positions were all on the northern face of Crete, which was just 100 kilometers away from from the Axis-occupied mainland.

The airfields at Maleme, Retimo, and Heraklion were locations of vital importance, as was the port at Suda Bay. These had to be defended, as the Allied high command was unwilling to destroy them because of their strategic importance.

Freyberg had a large force under his command, around 40,000, but they were poorly equipped and lacked the ability to communicate with each other effectively across the rugged, mountainous terrain of the island. This would prove to be a fatal undoing, despite the valiance of the men on the ground.

Within the 40,000 were 30,000 British, New Zealand and Australian troops and 10,000 Greeks. Most of these had been evacuated from the mainland after it fell to the Axis forces – many had their own weapons, but lacked the heavy armaments that would have made a difference in the fighting.

Along with the ground troops, General Archibald Wavell, commander-in-chief for the region, provided Freyberg with 22 tanks and 100 pieces of artillery. These guns were in such a poor state that they were stripped down and turned into 49 pieces of better quality.

Although the tanks and heavier weapons were a positive addition to the defending forces, they were too thinly spread across the island to be able to have a significant influence on the outcome of the failed defence.

The battle began on the 20th of May, 1941 after German paratroopers jumped out of their Junkers JU 52 airplanes and the majority landed near the Kiwi defended Maleme airfield. The invading force suffered badly during the first day, with a company of III Battalion, 1st Assault Regiment losing 112 of 126 men.

Of the 600 men who started the battle in III Battalion, 400 would lose their lives during the first day of the invasion of Crete. Those crewing the glider transport fared worse, as they were either shot down or the crews killed by defensive forces after landing.

Towards the evening of the 20th of May, German forces pushed the defenders back from Hill 107, which overlooked Maleme airfield. A second assault wave was also launched, and more Axis troops were dropped.

One group of enemy forces then attacked Rethymno, while a second began operations near Heraklion. Defensive units were waiting for the Germans, who suffered heavy casualties. Despite this, a breach was made in the defenses set up by the 14th Infantry Brigade, the 2/4th Australian Infantry Battalion and the Greek 3rd, 7th, and Garrison battalions.

However, the native units counter-attacked and managed to recapture the barracks on the edge of town as well as the docks – two important places around Heraklion.

As night descended on the first day of the battle, the Germans had not managed to secure any of their objectives, and the Allies were confident of repelling the invasion. Despite this confidence, things would soon change for the defenders.

On the 21st of May, 22nd New Zealand Infantry Battalion withdrew from Hill 107, which left Maleme airfield undefended. Communications had been cut between the commander and his two westernmost companies, and Lieutenant Colonel Leslie Andrew VC assumed this lack of contact was due to those two battalions being overrun.

Because of this, Andrew asked for reinforcements from the 23rd Battalion, which Brigadier James Hargest denied because he thought those men were fighting parachute troops. Andrew then mounted a counter-attack, which failed, and so he was forced to withdraw under cover of darkness with the consent of Hargest.

When Captain Campbell, who was commanding the western company of the 22nd Battalion, learned of the withdrawal he also conducted one – thus leaving the airfield to the Germans because one side of the island couldn’t talk to the other.

This terrible misunderstanding allowed the Germans to take the airfield unopposed, which let them reinforce their invading force with ease. It is probably the most important part of the whole battle, and is a huge reason in why the Allied forces lost the island.

Commanding the Axis forces from Athens was Kurt Student, who quickly moved to concentrate their forces on, and take, Maleme airfield and land more troops in via sea. In response, the Allies bombed the area – but it wasn’t enough to stop the 5th Mountain Division flying in by night.

A counter-attack was planned for the 23rd of May, but this failed because long delays in the planning process meant the attack took place during the day, instead of at night.

The two New Zealand battalions sent to take back the airfield faced Stuka dive bombers, dug-in paratroopers, and mountain troops. As the hours passed, the Allies withdrew to the eastern side of the island.

After four more days of hard fighting among inhospitable terrain, Freyberg was ordered to evacuate his troops from the island. Parts of the Allied force retreated to the south coast, and 10,500 were evacuated over four nights. 6,000 more were evacuated at Heraklion, while around 6,500 were taken prisoner after surrendering to the Germans on the 1st of June.

As the smoke cleared, it became clear that more than 1,700 Allied soldiers had lost their lives in the battle – while more than 6,000 Germans were sent to their graves by the defenders. Hitler was not impressed by these losses and concluded that paratroopers should only be used to support ground troops, and not be used as weapons of surprise.