Few spots in the world boast a history of conflict to match the Gallipoli region of Turkey. Troy, sitting on the Asian side and looking across to Cape Helles, tends to grab most of the attention. Poets and academics who served in the military during World War I and were assigned to work in Gallipoli were thrilled to know they would be in such close proximity to such a special historical site.

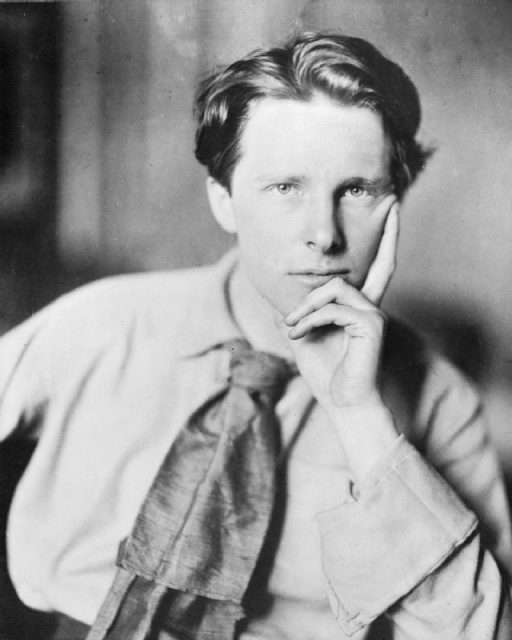

Rupert Brookes, the poet, was excited to know that he had been assigned to fight at Gallipoli near the site of the Battle of Troy instead of being sent to France or Belgium. Unfortunately for him, he never made it there. He died at Scyros, Achilles’ island, shortly before the landings at Helles.

Besides the famed battles of the Anzacs in World War I, there was the Ancient Greek war against the Persians in 480-479 BC. It can be argued that modern European society owes it’s very existence to the Greek victory in that war. When Herodotus wrote about that ancient war, he ended the tale in the small town of Eceabat, just up the road from where the Anzacs fought their bloody battles in the Great War.

Later, the Athenians and Spartans battled each other alongside their respective allies in the Dardanelles Straits. This was a part of the Peloponnesian war which took place from 431 to 404 BC. The Battle of Cynossema in 411 BC was one of those battles, with 160 ships battling near Eceabat, just up the channel from where the British and French navies were defeated by the Germans in WWI.

An even bigger battle at sea took place in 405 BC. The Battle of Aigospotami involved 350 ships. This battle led to the eventual defeat of Athens.

Later, when Alexander the Great marched through the area, he went to the tip of Gallipoli and crossed to Troy from there.

In World War I, the Allies made an attempt to wrest control of the region from the Ottomans, one of the Axis powers. Due to poor intelligence and no knowledge of the terrain of the region, the invasion stalled. Beginning with a failed offensive by the British and French navies and continuing with a land invasion on April 25th by the British, French, and Anzac troops, the invasion made little headway and evacuation of Allied troops began in December 1915. By that time, over 480,000 Allied troops had fought in Gallipoli with over 250,000 casualties – 46,000 died.

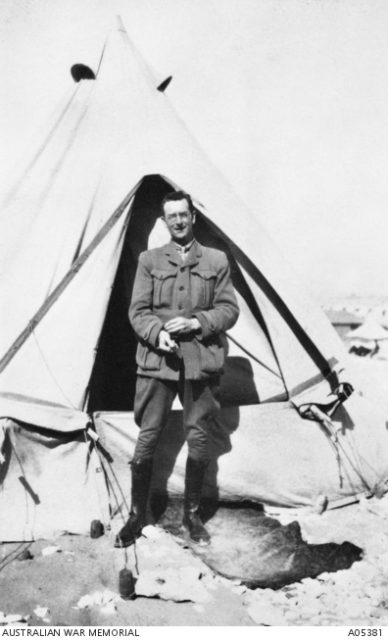

Charles Bean was Australia’s official historian of World War I. He landed with the troops at Gallipoli on April 25, 1915, and stayed on the front lines with them despite being injured. He then documented the battles at the front lines of Pozieres, Belgium and the Western Front in 1916.

Having studied the Classics, Bean was able to memorialize the heroes of those battles in the manner of the ancient Greeks without plagiarizing the great Classic authors and poets.

After the war, Bean wrote the official Australian history of the war. He ended his book, “Gallipoli Mission,” with a reference to the inscription to Athenian soldiers that died in the Dardanelles in 440 BC. But he did so without directly comparing the ancient Athenian warriors to the Anzacs in WWI.

Some Australian historians feel that it is a waste to study the ancient history of recent battle sites. They see ancient history as a distraction from what we remember of the sacrifices made by the country’s troops over one hundred years ago. It can be argued, however, that there is value in the added context when we remember those who sacrificed their lives in the past on the same ground the Anzacs fought for in WWI.