In 1961, the US government sponsored an invasion of Cuba to overthrow its prime minister, Fidel Castro. Though originally planned by the CIA under President Dwight D. Eisenhower, it was carried out by his successor, John F. Kennedy. The attack happened at the Bay of Pigs, for which it was named, though the Cubans know it as the “Battle of Girón.”

Despite having superior weaponry and funding, the invasion failed, leading to the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962 and heightening tensions between the US and the USSR. Though US-Russian relations improved after 1991, America’s official hostility toward Cuba still stands as of September 2015.

The CIA planned the invasion in 1960 under Deputy Director for Plans (DDP) Richard M. Bissell, Jr. Bissell created the 5412 Committee, a covert operations group staffed by those responsible for the 1954 Guatemalan Coup that ousted its president in favor of the military dictatorship of Carlos Castillo Armas.

There were many Cuban exiles in the US who wanted Castro gone, so Bissell called on their support. On 18 August 1960, Eisenhower gave the Committee $13 million to fund its operation, and by October 31, the CIA began training thousands of Cubans who were called Brigade 2506.

On 4 April 1961, Kennedy approved of what was then called Operation Zapata – because the US wanted the invasion to look like a purely Cuban affair. Cuba knew about the invasion and braced for the attack. There was nothing they could do about the American military base at Guantánamo Bay, but they had the US weaponry left by the previous regime.

The invasion began on April 14. US Navy destroyers grouped off Guantánamo Bay to make it look like the invasion was coming from that direction. Reconnaissance boats moved closer to shore, providing a diversion that allowed 164 Brigade members led by Higinio “Nino” Diaz to land near Baracoa, Oriente Province.

At dawn the next morning, Cuba launched a FAR (Fuerza Aérea Revolucionaria) T-33 reconnaissance plane over Baracoa, which fatally crashed into the ocean. Eight Douglas B-26B Invader bombers left Nicaragua, reached Cuba at 6AM, then split into three groups to attack the airfields at San Antonio de los Baños and Ciudad Libertad near Havana, as well as the Antonio Maceo International Airport at Santiago de Cuba.

The bombers had been repainted with the markings of the FAR to make it look like a local uprising, but were piloted by members of the Fuerza Aérea de Liberación (FAL) who were part of the Brigade. A ninth B-26 also left Nicaragua looking like it had been shot at. It flew toward Cuba then landed at the Miami International Airport, where the pilot sought asylum, claiming he was part of a revolt against Castro.

By 10:30AM, Cuba complained about the invasion before the UN, which the US denied, claiming it was a local uprising. Later that evening, Diaz’s group failed a second time to land at Baracoa. Under mounting pressure from the UN, Kennedy called off further aerial strikes on Cuba.

Before the day ended, US Navy fleets left Nicaragua, the Cayman Islands, and Vieques Island, assembling just outside Cuban waters. Before midnight, a boat made its way to Bahia Honda in Pinar del Rio Province, blasting the sound of a bigger flotilla approaching. Castro, who was at the Bay of Pigs, fell for it and made his way toward Bahia Honda.

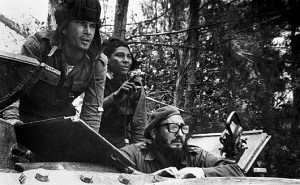

The actual invasion happened at midnight on April 17. Four transport ships loaded with tanks, ground vehicles, and Brigade members entered the Bay of Pigs. Blagar, the lead ship, unloaded at Playa Girón at 1AM, followed by the Barbara J. at Playa Larga. The local militia reported the landings before being killed.

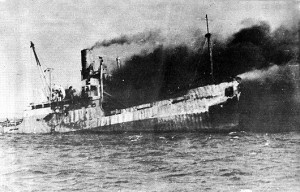

At 6:30AM, three FAR Sea Furies, two Lockheed T-33 fighter jets, and one B-26 bomber attacked the transport ships, damaging the Houston. Some 270 Brigade members made it to Girón, but 90 of them were killed. By 6:50AM, the survivors could no longer fight on the beaches since their equipment were still on the besieged ships.

To prevent more Cuban reinforcements, two FAL B-26 planes sank the El Baire, a Cuban Navy Patrol Escort, at 7AM. They continued on to Girón and were joined by two more B-26s to attack Cuban ground troops and provide cover for the Brigade members and ships.

By 7:30AM, Operation Falcon parachuted 177 Brigade members into Cuba. The planes went on to drop equipment and supplies near the Australasia Sugar Mill, but many landed in swamps. Thirty minutes later, FAR Sea Furies and T-33s destroyed the Rio Escondido, preventing more people and equipment from making it to Cuba.

At noon, the Blagar shot down a FAR B-26, while FAL B-26s attacked lightly armed Cuban forces advancing into Playa Larga. A FAR T-33 shot down three FALs, but their pilots were rescued at sea.

Invasion Day Plus One (D+1) on April 18 showed that Cuba was not easy to take. The Brigade was retreating toward Girón and San Blas. At 5PM six FAL B-26s attacked a column of buses, tanks, and trucks with bombs and napalm, then flew toward Girón where they resupplied the airstrip seized by the Brigade.

D+2 on April 19 was a disaster for the Americans. Kennedy ordered six fighter planes to strafe Cuban airspace. Two FAL B-26s piloted by the Alabama Air Guard were shot down. The USS Essex responded by sending the VA-34 squadron over Cuban air space to intimidate the FAR, but were ordered to avoid combat unless necessary. Without their help, the Brigade were forced to retreat as 20,000 Cuban troops made their way to Girón.

D+3 on April 20 was a clean-up job. Dusk saw the USS Eaton and the USS Murray evacuating the Brigade from Cochinos Bay, till Cuban troops began firing at the ships, forcing them to retreat. Some 1,200 were left behind.

The aftermath was a political embarrassment for the US, as they could no longer deny involvement in the affair. It also strengthened Castro’s grip over the nation and forced him to side with the Soviets.