Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7 1941, the United States and its allies in the Pacific were subjected to a series of enemy victories, with the nation conquering territory after territory. It wasn’t until the battles of the Coral Sea and Midway the following year that the Japanese war machine was finally slowed down, with the progress made serving as the morale boost needed to succeed in the Battle of Bismarck Sea in March 1943.

Where did the fight in the Pacific stand?

Following the Battle of Midway and into late 1942, Japan began to realize its forces were at risk of losing control of the Southwest Pacific, particularly New Guinea. With renewed vigor, the Allies launched several offensives on the island, with the aim of taking control of the Japanese base on Rabaul, New Britain. If they were successful, the hope was they’d then begin efforts to liberate the Philippines of enemy troops.

Of the Allied nations involved in the operations, Australia was particularly concerned about Japan’s expansion in the region, given how close it was to the Australian-held territory of Papua.

Bulking up defenses in the lead up to the Battle of the Bismarck Sea

With the Allies putting up a strong fight during the Guadalcanal Campaign, the Japanese knew they needed to shore up any and all defenses they had in the Southwest Pacific. In late 1942, several divisions were sent to New Guinea, followed by more troops once Guadalcanal was evacuated in January ’43.

Little did the Japanese know that the Allies were aware of their movements, thanks to intelligence gathering. Aircraft with the US Army Air Forces (USAAF) and the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) attacked a convoy of ships moving from Rabaul to Lae, New Guinea, and successfully downed 69 enemy aircraft and the transport SS Nichiryu Maru.

However, they couldn’t stop those who remained from reaching their destination.

Following the encounter, the Allied forces conducted regular reconnaissance on New Guinea. Before long, it was learned that the Japanese planned to land another 6,900 troops in the region, a move that not only concerned Gen. Douglas MacArthur, but put the plan to build up the region at risk. This led to the development of newer, more effective bombing tactics – such as mast-height (skip) bombing – to make better use of the aircraft available.

Commencing the Battle of the Bismarck Sea

A newer Japanese convoy left Rabaul on February 28, 2023, with its final destination being New Guinea. The troops and vessels were blessed with poor weather during the journey, which initially hid them from Allied reconnaissance aircraft. By March 2, the Allies had spotted the convoy, prompting Brig. Gen. Ennis Whitehead to launch eight Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses, which were followed by another 20, then 11 more by day’s end.

By the end of March 2, the Japanese convoy was approaching waters within range of all Allied aircraft, at which point what can only be described unreserved devastation would be unleashed. To ensure the attack began as soon as possible when night gave way to daylight, Royal Australian Air Force-flown Consolidated PBY Catalinas followed the enemy vessels and reported on their positions.

Night gives way to daylight

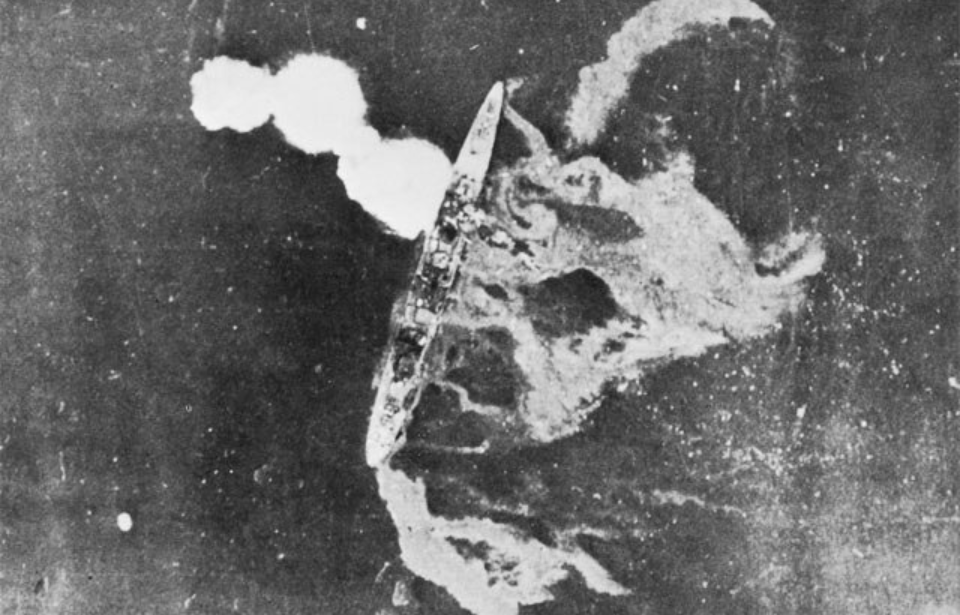

Daylight broke on March 3, 1943, to clear skies – ideal conditions for an aerial assault. That morning, some 90 Allied aircraft took off to attack the convoy, made up of B-17 Flying Fortresses, Lockheed P-38 Lightnings, North American B-25 Mitchells, Bristol Beaufighters and Douglas A-20 Bostons.

The heavily-armed Beaufighters strafed the enemy ships at an extremely low level, in an attempt to destroy their anti-aircraft capabilities and take out their captains and officers. This was unexpected, with the Japanese expecting them to make torpedo attacks. The B-17s conducted medium-level bombings, while the B-25s and A-20s attacked at extremely low altitudes.

At the same time, the P-38s engaged Japanese escort fighters above the chaotic scene.

The Japanese didn’t take the assault lying down. Mitsubishi A6M Zeroes fought the B-17s, and while they managed to destroy some Allied aircraft, their efforts weren’t enough to turn the tides of the battle in their favor.

Wiping out the entire Japanese convoy at New Guinea

The Battle of the Bismarck Sea was a massive defeat for the Japanese. Not only were all eight transports struck by Allied attacks, so, too, were three destroyers. While the rest of the vessels picked up survivors, they weren’t out of the woods yet, as the Allies launched a renewed assault on the convoy with PT boats, sinking a fourth destroyer, the Asashio. Those adrift on rafts were also targeted over the subsequent days, out of fear they’d make their way to land and resume the fight.

Overall, the Japanese lost all eight of their transports and half of the destroyers that made up the convoy, along with over 3,000 sailors and soldiers to action or drowning. The Allies faired much better, reporting the losses of just 13 men (another eight were wounded) and six aircraft.

In the aftermath of the engagement, Japanese transit routes to Lae, New Guinea had to be changed, due to the growing Allied threat, and the country’s military issued an order that all troops learn how to swim, given the high number of losses.

More from us: Operation Market Garden Led to a Decades-Long Treasure Hunt That’s Still Ongoing

The Battle of the Bismarck Sea also served as one of the catalysts for Operation I-Go, the Japanese counteroffensive against the Allied forces on New Guinea and in the Solomon Islands. While the aim had been to disrupt Allied operations, to give Japan enough time to rebuild and plan out a better offensive strategy, the operation wound up only causing minor setbacks and delays.