They say that there is always someone who will make money out of a war and the Civil War was no exception.

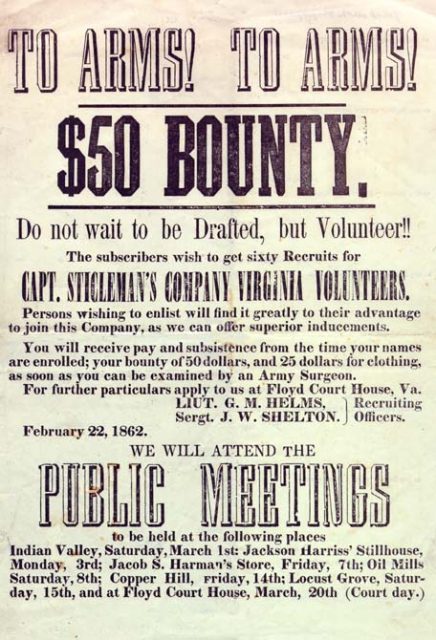

One of the ways that some people tried to make a quick buck was to enlist in the place of someone who did not want to enlist – for a fee. Having received the money, these con men (known as bounty jumpers) would then desert and enlist again somewhere else to receive another bounty payment.

Some were remarkably adept at getting away with it and made a comfortable living from it for a while.

Paying to dodge the draft

Perhaps one of the most surprising things is that it was perfectly legal to pay someone to enlist in your place. In fact, it was actually encouraged by both the Union and Confederate sides – although, of course, bounty jumping was not.

The logic behind it was that allowing men to pay others to enlist in their place would lead to an increase in the number of soldiers enlisting.

Maximum fees were set by law early in 1863 as part of the Draft legislation. The fee that could be paid varied according to where you signed up.

The North allowed much higher fees of up to $300. When you consider that such a figure works out at around $9,000 in today’s money, you can understand why people were tempted to try it. But perhaps it was not quite enough to make them want to stay on to fight and risk their lives in battle.

Fees in the south were lower, starting at $50 and going up to a maximum of $100. In addition to this, the dollar in the north was worth more, so bounty jumping was a bigger problem for the Union. Serious bounty jumpers signed up for various regiments on either side which may have reduced the likelihood of getting found out.

Some Famous Bounty Jumpers

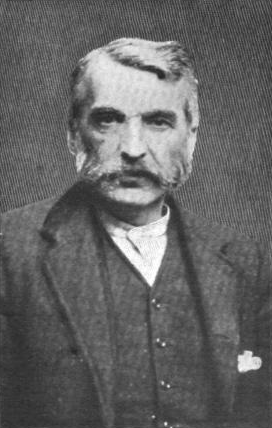

Among the most famous must be Adam Worth. He was a known criminal but somehow managed to escape from this exploit without being caught. Worth went on to become a notorious international criminal and art thief.

He is believed to have been the inspiration for the fictional character “Professor Moriarty,” Sherlock Holmes’s nemesis in the popular detective stories by Arthur Conan Doyle.

Others included two Englishmen, James Hayden and Francis Leonard, who were arrested after enlisting and taking the money under various false identities. Another who ended up in prison managed to enlist 32 times before being found out.

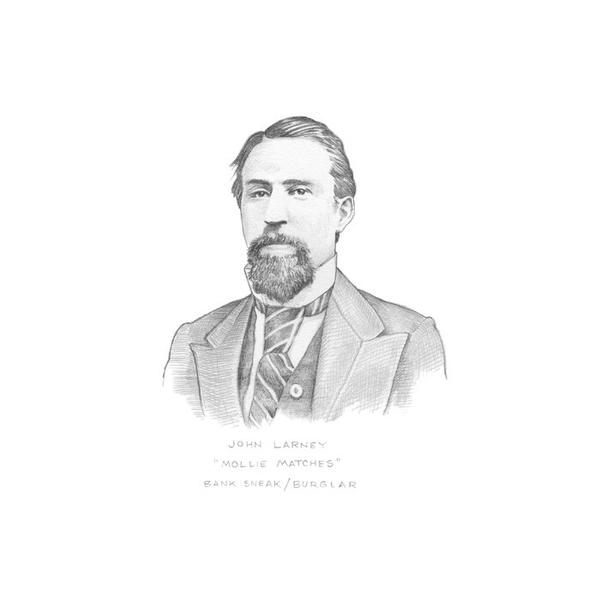

But the record must go to John Larney who claimed to have enlisted in 93 different regiments and received thousands of dollars in bounties. Larney was a career criminal and a pickpocket. He also went under the name of Mollie Matches since one of his other ploys was to disguise himself as a match girl and pick the pockets of potential customers.

Risk of Death or Imprisonment

The bounty money must have been an enticing prospect, especially when many people’s incomes and stability would have been severely disrupted by the war. But of course, it was a crime and carried a high penalty if caught.

Even deserting the military was, in theory, punishable by death although in practice executions were rarely carried out. It was far more efficient to return deserters to the ranks.

However, bounty jumpers did often face death and even torture. They would be made an example of to discourage others.

It is not known how many were caught or punished. However, one group of five paid the ultimate price after enlisting with the 118th Pennsylvania Regiment and deserting shortly afterward. The five were captured and, despite making appeals for clemency to President Lincoln, they were executed.

James Develin was executed in 1865 after his jealous wife found out that he had been with another woman and she reported him to the authorities.

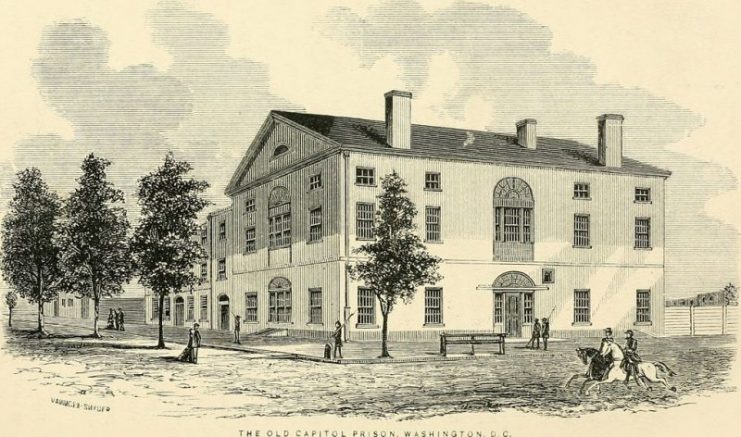

However, many got off more lightly, and a good number ended up in prison, including one man who had made 32 false enlistments and received a remarkably light sentence of only four years.

Catching the Bounty Jumpers

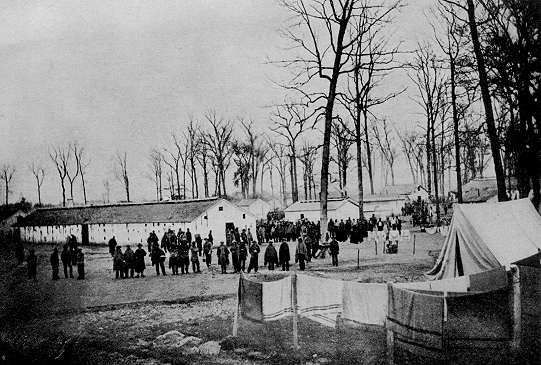

All this, of course, caused problems for the troops on both sides but particularly for the North as the financial rewards were greater. Many were drawn to New York City, and an estimated 3,000 bounty jumpers were believed to be in the city at one time.

Consequently, New York was the best place to catch them and a serious campaign to pursue them started in February 1863. This was fairly successful, catching around 12 per day although it did not continue for very long.

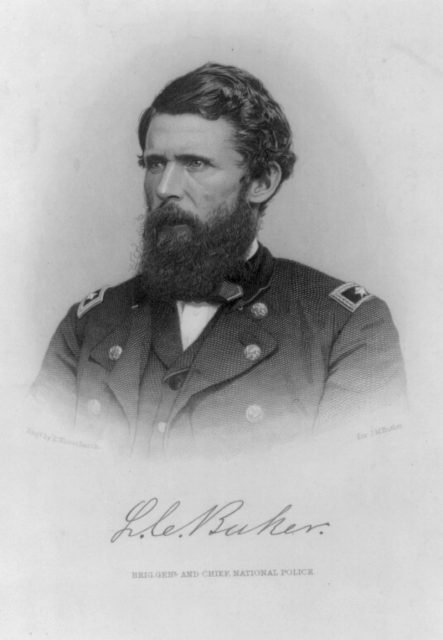

An even more successful attempt to round them up was carried out thanks to the efforts of Lafayette Baker, a New York-based detective who was credited with catching 183 in just one day. Baker’s method was original. He set up a fake recruiting office and just waited for them to show up to enlist.

Unfortunately for Baker, he had rented the office from an unscrupulous businessman who stole the funds to be used for catching the bounty jumpers – the grand sum of $50,000. So Baker never received a reward for his efforts, despite his successful methods.

End of the Bounty Jumper

By the end of 1863, both sides had started to realize that the system would have to be abandoned. The practice of paying bounties to avoid the draft was made illegal. Although it had originally been introduced as a way of getting more men to fight, it turned out to have the opposite effect and was causing more problems than it solved.

The bounty jumpers’ stories remain part of the folklore of the Civil War and have even been commemorated in song.

In 1866, they were immortalized in a song with music by W Arlington and words by J B Murphy who were popular composers of the era. In The Bounty Jumper’s Lament, a prisoner looks back with regret on the extravagant life he lived with his bounty money. He bids farewell to his sweetheart as he hears the “tramp tramp tramp” of the guard coming to take him away – presumably to be executed.