At 6 o’clock in the evening of November 9, 1989, a befuddled low-level member of the Soviet East German Politburo gave a press conference to announce reforms to the laws that were in place regarding the border between East and West Germany.

Although the reforms were entirely superficial and did not specifically address the desire of the East German populace to cross into West Germany, the politburo was under immense pressure to execute some kind of visible reform in light of massive street protests demanding changes similar to Gorbachev’s Glasnost (“Openness”) policies.

The reforms that were announced were entirely a gesture of appeasement. Any promises of freedom of travel were mooted by clauses spelling out exemptions to such freedoms in the name of national security. However, despite the intent of the East German government to keep their borders closed, they would be opened that night.

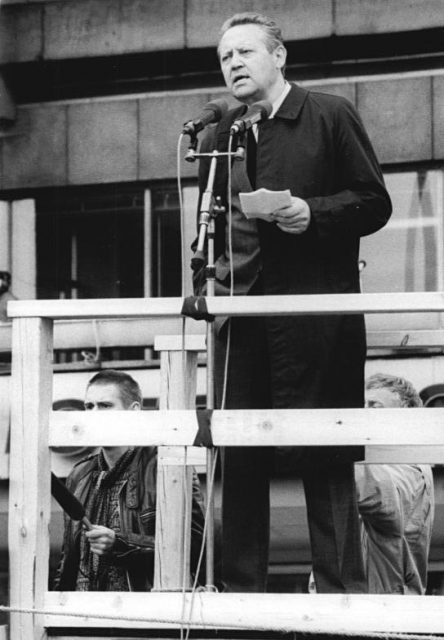

In an hour-long, rambling press conference that American journalist Tom Brokaw described as “boring,” Politburo official Günter Schabowski delivered a long-winded sermon on the “new” regulations and strayed little from the Politburo’s talking points. At the end of the press conference, however, the benign prodding of an Italian journalist set events in motion that would open a border that had been closed for three decades within hours.

When asked pointedly about travel under the new regulations, Schabowski became confused and struggled to answer the journalist’s question. Recalling that he had been instructed to publicly mention the new regulations, Schabowski began to read from his copy of the regulations for the first time. Schabowski had not been involved in the preparation of this legislation and was unfamiliar with it when he began to recite passages.

He began by confusingly stating, “[i]t is a recommendation of the Politburo that has been taken up, that one should from the draft of a travel law, take out a passage,” and then proceeded to read clauses from the legislation. The briefing he was handed, however, was supposed to be read the following day.

More importantly, it was intended to be read in its entirety so that all of the caveats and national security exemptions could be delivered at the same time. Schabowski, however, scanned the document and announced only its most eye-catching features. When the assembled press heard Schabowski listing off “exit via border crossings” and “possible for every citizen” as elements of the new legislation, he was instantly assaulted with demands for clarification.

“When does that go into force?” shouted one journalist.

“What will happen to the Berlin Wall now?” asked another. Surprised by the ferocity of the response he had just elicited, he scanned the document again.

“Immediately, right away.”

At the time of this mistaken announcement, much of the East German Politburo was engaged in closed-door meetings, and the Soviet leadership in Russia was for the most part already asleep owing to the time difference.

The East Germans who were able to illicitly view West German television saw the press conference, though, and so did the East German border guards. As the press began to broadcast the news worldwide, the East Germans began to flock to the border wall demanding safe passage across.

The situation escalated rapidly, and as one guard recalls, they were severely outnumbered by a raucous crowd. Harald Jager recalls telling his fellow guards that Schabowski’s comments were “deranged,” but they were soon beset by the decision of whether to allow the growing crowd passage or attempt to push them back with violence.

At approximately 11:30 pm, the wall was opened and thirty years of segregation come to an end – all because a sharp journalist asked the right question of an incompetent civil servant.