On July 31 1986, Chiune Sugihara passed away peacefully in a Japanese hospital. This quiet, unassuming family man single-handedly saved the lives of at least 6,000 Jews during World War II, and while he is one of many hundreds of people that could not reconcile their own code of morality with that of their governments at that time, his efforts to rescue people have gone largely unnoticed by the world.

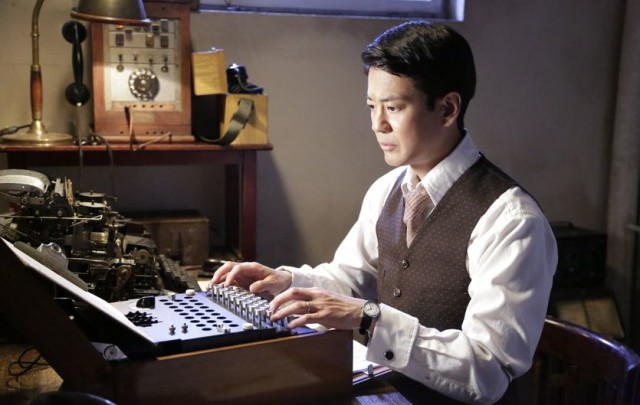

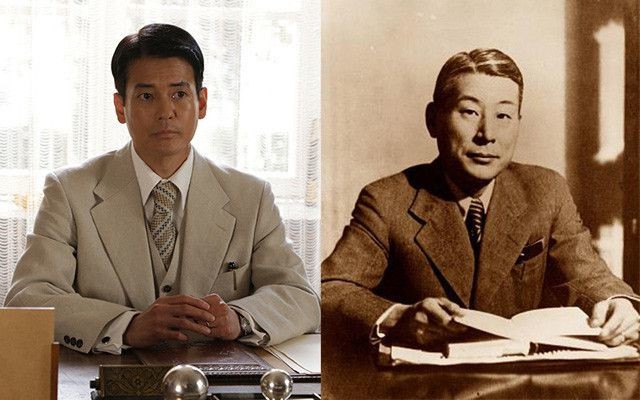

The audacious true story of the Japanese diplomat who acted against orders to save thousands of Jewish lives from Nazi extermination gets a sweeping, big-screen treatment in the epic biopic PERSONA NON GRATA. Scroll down for trailer.

Chiune Sugihara was a New Year baby, born on January 1, 1900, in Yaotsu in Japan. He was one of six children, having four brothers and one sister. He graduated from secondary school and, while his parents wanted him to become a doctor, he had other ideas and instead went to Waseda University. There he majored in English and eventually, after taking the time to improve his English, he passed the entrance examination for the Japanese Foreign Ministry; he was recruited into the Ministry in 1919.

His first posting was to Harbin in China where he took the time to master both German and Russian and became an expert on Russian affairs. His innate sense of justice was evident at an early age when he resigned his post as Deputy Foreign Minister in Harbin in protest over the treatment meted out to the local Chinese people by the Japanese. He had married a Russian lady but divorced her before returning to Japan in 1935. On his return to Japan, he remarried, and his wife bore him four sons.

Sugihara’s next posting was to Kaunas in Lithuania where he was given the post of Vice-consul at the Japanese Consulate. One of his duties was to keep an eye on German and Russian troop movements, reporting to the Foreign Ministry in Berlin and Tokyo any plans of attack by the Germans on the Russians.

In September 1939, the Germans invaded Poland and with the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in existence, the Russians invaded Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia – they feared the Germans would use these Baltic States as a launch pad into Leningrad. This invasion caused terror amongst the Jewish people, who set about trying to get exit visas to leave the country. They had learned of the treatment handed out to Jewish people in Germany by Jewish refugees that had fled from Poland.

It was impossible to travel without a visa, but there were many thousands of Jewish people trying to get one. The Japanese Foreign Ministry’s policy was that no visa could be issued unless the traveler had undergone the official immigration process and had sufficient funds, or they had a visa for a third destination outside of Japan. Sugihara contacted the Foreign Ministry three times trying to get permission for these people as they had a legitimate fear of being rounded up by the German authorities.

The Dutch ambassador had been issuing visas for an official third destination to the Dutch colony of Curacao in the Caribbean, or to Surinam. Again, Sugihara’s deep moral code revealed itself, and he spoke with his family about ignoring the instructions given by the Foreign Ministry. Given the Japanese culture, this was a significant act of disobedience and must have disturbed him and his family.

In mid-July of 1940 Sugihara started to issue a ten-day transit visa through Japan to as many Jewish people as he could, and he arranged with the Russian authorities for the Jewish people to travel on the Trans-Siberian railway, though at the vastly inflated price of five times the normal fare.

He wrote furiously, spending up to twenty hours a day turning out these precious documents, many of which went to the head of a household so as to enable the entire family to travel on one document. It is estimated that he issued over 6,000 visas up until the 4th of September, 1940 when the consulate was closed.

Even then he did not stop trying to help desperate Jewish families; he continued to write visas from his hotel room and eventually he simply affixed the consulate seal and his signature onto a blank piece of paper to be thrown from the train window. The people could then write their own visa, and Sugihara hoped that it would be enough to help them escape to freedom.

After leaving Lithuania with the closure of the consulate, Sugihara was assigned to Prussia before serving as Consul General in Prague. In 1942, he was moved to Bucharest in Romania. When the Russians invaded Romania, Sugihara and his family were interred in a prisoner of war camp for eighteen months. On being released in 1946, he was asked to resign from the Foreign Ministry, ostensibly due to downsizing, but his wife was convinced it was due to his disobedience in Lithuania.

Sugihara settled in Japan with his wife and his sons and took on some low paying jobs. In later years, using his knowledge of Russian, he worked at several lowly jobs in Russia while his family remained in Japan.

Years later Sugihara wondered why no one from the Foreign Ministry ever took him to task over the number of visas that he wrote. His only explanation was that perhaps no one really calculated how many he gave out. The actual number of people saved by this courageous and deeply moral man has never been officially calculated, but informed sources put it as high as 10,000 people. Many of these were heads of families so the actual number of people could be much higher.

In 1968, one of the young people that Sugihara had saved, Jehoshua Nishri, who was an economic attaché with the Israeli Embassy, found him and visited him. Sugihara was invited to visit Israel in 1969, and when he arrived he was greeted by the Israeli government. The people that he had saved, the so-called Sugihara Beneficiaries, called for his inclusion in the Yad Vashem Memorial.

Finally, in 1985 Chiune Sugihara was granted the “Righteous Among the Nations” by the Israeli government. As he was too ill to travel, the honor was given to his wife and son. Sugihara and his descendants have perpetual Israeli citizenship in recognition of his compassion and bravery.

When he was granted this honor he was asked why he had done what he had done, knowing it was breaking the law and could have resulted in trouble for himself and his family.

He had the following to say: “People in Tokyo were not united. I felt it silly to deal with them. So, I made up my mind not to wait for their reply. I knew that somebody would surely complain about me in the future. But, I myself thought this would be the right thing to do. There is nothing wrong in saving many people’s lives…The spirit of humanity, philanthropy…neighborly friendship…with this spirit, I ventured to do what I did, confronting this most difficult situation – and because of this reason, I went ahead with redoubled courage.”

This humble man did not crow about his achievements, and it was not until a large delegation from Israel, including the Israeli Ambassador to Japan, attended his funeral that his neighbors knew what he had done.

He has remained a largely unknown hero, but one must think that out there in the world are doctors who save lives, scientists who make discoveries, teachers who develop minds, and families that have grown old together purely as a result of this humble man who just wanted to help people in need.

Though he has always been a national hero in Lithuania, his story was rarely heard in Japan or elsewhere, until the premiere of “Persona Non Grata,” which, when it was released on December 5 in Japan, earned a second place among movies opening that day.

“Persona Non Grata” will enjoy its U.S. premiere Jan. 31, when it is screened at the Atlanta Jewish Film Festival, which begins Jan. 26.