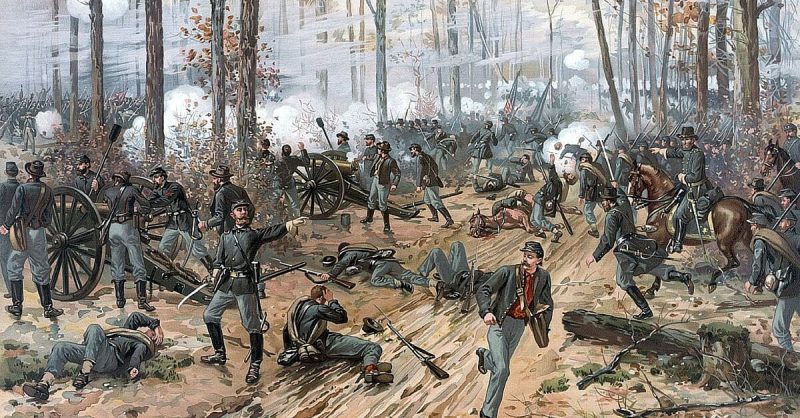

There are many remarkable stories of the American Civil War. One of the most striking, however, is the story of the soldiers who glowed in the dark. By the spring of 1862, it was clear that the Civil War was going to be bloody and long . Major General Ulysses S. Grant had pushed deep into the Confederate-led South along the Tennessee River. That April, he camped at Pittsburgh Landing near Shiloh, Tennessee, waiting for the arrival of Major General Don Carlos Buell and his army.

Confederate troops were entrenched near Corinth, Mississippi, they launched a surprise attack on Grant’s troops in hopes of defeating them before the second army joined up. Grant’s men had already been increased in number by some troop arrivals from Ohio. They held their ground and established a battle line that was backed by artillery. Fighting went on through the night, but by the morning the remaining troops traveling from Ohio had arrived. Now the Union outnumbered the Confederates by more than 10,000.

The Union troops pushed the Confederates back until they retreated to Corinth. The Confederates realized they could not win and did not launch another attack until August. But the Battle of Shiloh was a bloody massacre that medics on both sides were not prepared to deal with and this increased the number of casualties. In total, 16,000 soldiers were left wounded and over 3,000 died on that battlefield.

Soldiers of that time were not only battling wounds from bullets and bayonets, but they were very prone to infections. The shrapnel and dirt would infect their wounds. The warm, moist environment of the battlefield led to bacteria attacking the already damaged tissue. Given the all-around awful conditions during the Civil War, soldiers were always operating with weakened immune systems. This further diminished their ability to fight off bacterial infections on their own. Antibiotics had not yet been discovered, and often army doctors could not help the wounded. Sadly, this led to many soldiers dying from infections that would easily be remedied in today.

During the battle at Shiloh there were not enough medics to go around. Some of the soldiers had to wait two days and nights in the mud for medical treatment to reach them. By the time dusk fell on the first night some of the soldiers noticed a strange glow coming from their wounds. The faint light could be seen in the darkness of the battlefield. It turned out, when the troops eventually made it to field hospitals, that those who had had glowing wounds saw their wounds heal faster and were more likely to live to fight another day. It seemed that the glow was of some kind of protective effect, which earned it the nickname “Angel’s Glow.”

When 17-year-old Bill Martin visited the Shiloh Battlefield with his family in 2001 (140 years after the actual battle), he listened to the story of the glowing wounds with interest. His mother is a microbiologist at the USDA Agricultural Research Service, and she has studied luminescent bacteria that lives in soil. Martin told Science Netlinks that he asked his mom if these bacteria could have caused the wounds to glow. Being a scientist, she told her son that he should conduct an experiment to find out.

Martin and his friend Jon Curtis started off studying the bacteria and familiarizing themselves with the conditions at the Battle of Shiloh. He discovered that the bacteria his mother had studied, Photorhabdus luminescens, and the one from the glowing wounds both experience the same odd lifecycle. Both live in the guts of parasitic worms called nematodes. Nematodes burrow into insect larvae and reside in the blood vessels. Then they vomit the P. luminescens bacteria living inside them.

This bacteria is bioluminescent and gives off a soft bluish glow. It begins to produce a number of chemicals that kill the insect host along with all the other microorganisms already inside. The P. luminescens and nematode partner are left to feed, grow, and multiply without interruption. Eventually the nematode will eat the bacteria. The bacteria will then re-colonize the nematode’s guts so they can get transported as they burst from the corpse in search of a new host.

The two boys were able to determine from historical records that the weather and soil conditions were conducive for both the P. luminescens and their nematode partners. However, these bacteria cannot live at the human body temperature, making the soldiers wounds an impossible host. However, many of these soldiers were stuck out in the springtime rain for many hours before receiving medical treatment. It is highly likely they suffered from hypothermia, which would have reduced their body temperature enough to make them a viable home for P. luminescens.

The boys concluded that the evidence proved that the bacteria along with the nematodes got into the soldiers’ wounds from the soil. It turns out this might have saved their lives. Essentially the bacteria clears out pathogens that might have caused further infections that the soldiers would not have been able to combat. Neither P. luminescens nor the nematode is infectious to humans, which means they would have been eventually defeated by the immune system. Nematodes can cause ulcers, though, so it is not an ideal treatment for humans by any means.

Yet considering the dire conditions during the Battle of Shiloh, some of the soldiers were fortunate to have come in contact with this dynamic bacterial duo. The tale of these glowing wounds is one of the most remarkable stories of the Civil War and should be more widely known.