Kayaks, or canoes, have been used in warfare for as long as humans have been building boats.

However, we tend to think of them as having mostly been used in pre-modern warfare, generally by indigenous people and islanders. As ancient a concept as war canoes are, they have actually been used in wars of the 20th century too.

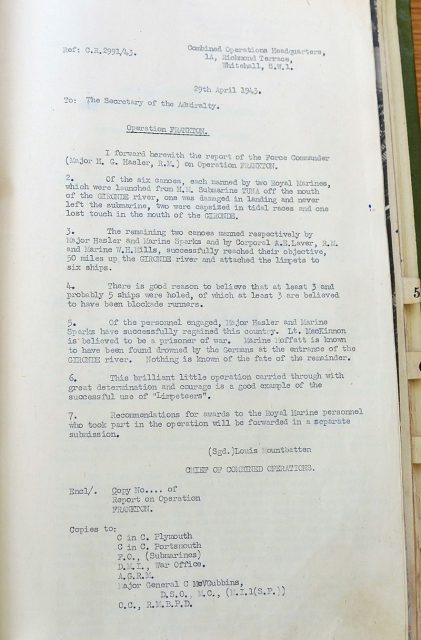

The most notable use was by British Royal Marines who, in the Second World War, launched a daring raid behind enemy lines in special collapsible canoes. The mission was called Operation Frankton and was led by Major Herbert “Blondie” Hasler, a formidable if slightly eccentric Royal Marine officer.

Canoes had been used by the British on a small scale during the early stages of the Second World war – mostly for reconnaissance or small, low-risk raiding – but Hasler was convinced that canoes could be effective for a far more potent purpose: attacking and, hopefully, sinking enemy ships in their own harbors.

In 1941 he submitted to the Admiralty a plan he had devised to do just this, using specially-designed collapsible canoes. Permission was granted for Hasler to set up a special force for this purpose. So, in 1942, he created the Royal Marines Boom Patrol Detachment (RMBPD).

The plan Hasler had in mind was to use collapsible canoes, given the name Cockle Mk II, to attack German ships in the Nazi-occupied Bordeaux Harbor. The Germans were using the harbor to evade the British blockade and bring in crucial industrial supplies from the East.

Sinking some of the merchant ships that ferried in these important raw materials would strike a powerful blow against the Germans.

Hasler’s plan was to have his specially-designed canoes brought close to the mouth of the River Gironde by submarine. His team of twelve commandos – two per Cockle Mk II – would then row the canoes via the estuary into the Bordeaux harbor.

This would be a long journey of over 90 miles and would take a few nights, moving only under cover of darkness.

Once in position, they would use limpet mines, attached via magnets below the waterline to the hulls of German watercraft, to sabotage and sink a number of ships. Then they would make their way overland to safety in Spain.

Operation Frankton was launched on the night of December 7, 1942. Each RMBPD commando who embarked on the raid was equipped with a .45 ACP pistol, a Fairbairn-Sykes fighting knife, four limpet mines, two grenades, and food and water rations.

In preparation for the mission, they underwent extensive training on canoes in the Thames and the Swale river. By the time the night of the 7th rolled around, it seemed as if the commandos were ready for anything.

Unfortunately, Operation Frankton did not get off to a very good start; the tidal forces at the mouth of the River Gironde were much more powerful than the men had assumed they would be. The canoeists encountered five-foot waves close to the river mouth. Despite their training, one of the canoes capsized. The two men in the canoe died at sea.

After this tragic mishap, the men proceeded with caution, but even so, two of the canoe crews were captured en-route. These commandos did not survive the mission either. Hitler’s “Commando Order” stated that any enemy soldier captured in Nazi-occupied territory would be executed immediately, and this was the fate of the captured RMBPD commandos.

Two canoes – one with Hasler in it – finally reached the Bordeaux Harbor after five nights of grueling paddling. Thankfully, the waters of the harbor were calm and placid. The RMBPD commandos were able to place mines on six ships in total before escaping the harbor.

They headed back through the estuary and, after finding a suitable spot to dispose of their canoes, they sank them and set off on their overland journey.

The overland journey, like the mission itself, did not go as smoothly as Hasler had hoped. He and his partner, Bill Sparks, were separated from the other two surviving commandos. The latter two were later captured by the Germans. Again, Hitler’s “Commando Order” came into play, and they were put to death.

On the 18th of December, Hasler and Sparks reached the French town of Ruffec, where a member of the French Resistance helped them to hide from German authorities for 18 days. After this, he guided them to safety via the Pyrenees, where they crossed the Spanish border.

The daring mission, even though it resulted in the deaths of ten of the twelve commandos who participated in it, was not a complete failure. The mines they planted on the six ships in the Bordeaux Harbor caused extensive damage, although none of the ships were put completely out of commission.

It was also discovered – after the fact – that the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) had also been planning a raid on the Bordeaux Harbor at this time. Their raid most likely would have been less risky than Operation Frankton and would have resulted in far fewer British casualties.

If anything, the consequences of this mixup at least convinced the various British military and intelligence departments of the need for better interdepartmental communication.

Photo by VVVF –

CC BY-SA 4.0

Hasler was awarded the Distinguished Service Order, and Sparks was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for their efforts in the raid. In 1955, a film, The Cockleshell Heroes, was made about the commandos of Operation Frankton. It went on to become a box office success.

Hasler, meanwhile, remained passionate about boats and sailing long after the war was over. He ended up inventing a device that allows a yacht to be sailed single handed – a mechanism that is still used on yachts today.

He died in 1987 in Glasgow.