Samuel Tom Holiday was well into his senior years before his friends and family had any idea how much he had contributed to the Allied cause during the Second World War.

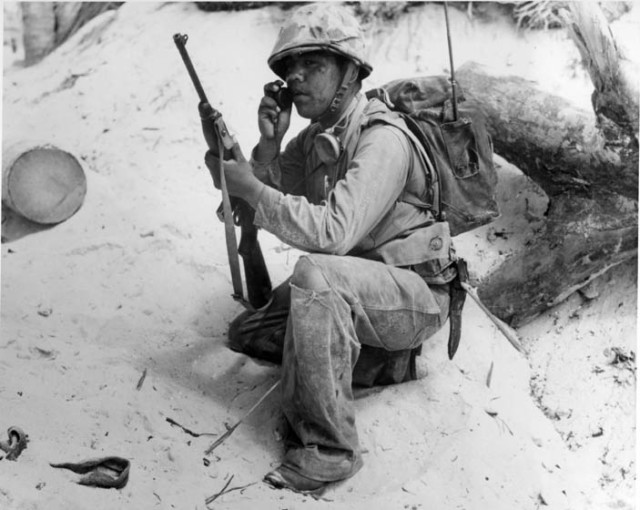

It was common knowledge that Holiday had enlisted in the Marine Corps at 19 years old and battled Axis forces all across the Pacific theater, from Saipan to Iwo Jima and the Marshall Islands.

His family was also aware that, despite having a mortar explode near his ear, he never felt his life was in danger during combat because he carried items sacred to the Navajo in a pouch around his neck wherever he went.

They were doubtless proud of his Purple Heart and other recognitions that he earned – but it would be over two decades after the end of WWII before the magnitude of his contributions began to see the light of day.

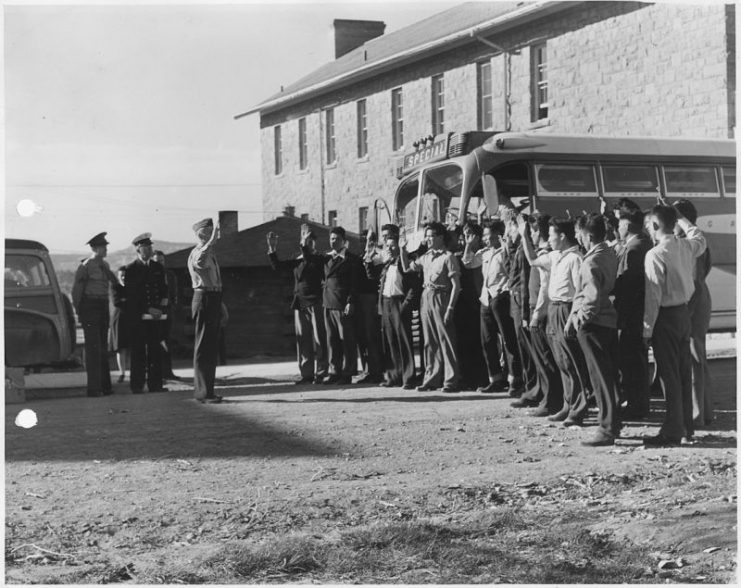

In 1968, the United States declassified the Code Talker program of which Holiday was a part. At the height of the war in 1942, the Marine Corps recruited 29 Native American servicemen to develop an unbreakable code based on their language that the Allies could use to coordinate the war without fear of Japanese radio surveillance.

While successive iterations of the German Enigma code were frustrating the Allies’ attempts to snoop on Axis radio communications, the code that the Marine Corps developed was impenetrable. The code was developed within 2 weeks, and the program was expanded to include 400 Native Americans who were trained in the code and deployed throughout the Pacific.

The program was a tightly-controlled secret until its declassification, and Holiday said little about his involvement until the 1980s.

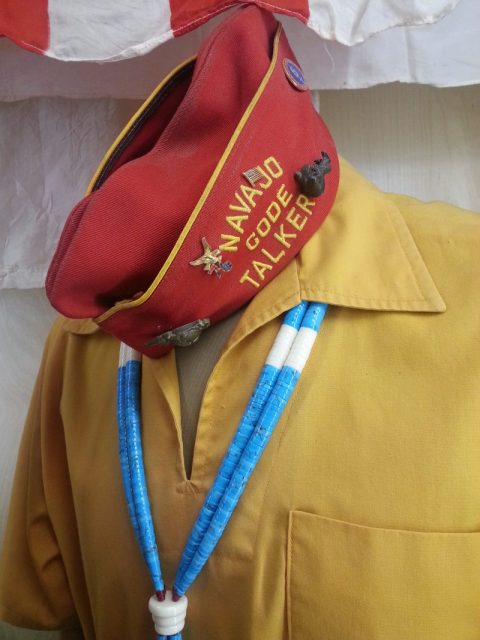

Holiday and the other Code Talkers were awarded a Certificate of Recognition for their work in 1992 by then-president George Bush Sr., and in 1994 he received a Congressional Silver Medal from Bush’s successor, Bill Clinton.

As knowledge of the program began to spread, Holiday himself began to speak about the highly-successful code the Allies used; it is difficult to estimate exactly how many lives the Code Talkers may have saved by using their languages to stonewall enemy codebreakers. The Allies’ debt to these men – some volunteers, and others drafted into service – cannot be overstated.

Two codes were developed by the original 29 Native American specialists – type one, which involved assigning a Navajo word to each letter of the alphabet, and type two, which were literal translations.

The Code Talkers often had to develop new words to describe modern technology, resulting, for example, in translations of “ship” and “cargo plane” into descriptors “house on water” and “eagle”.

The resulting communications were secure because of the Axis forces’ total lack of familiarity with Native American languages, and the code was successfully used without being broken through the end of the War.

With Holiday’s death on June 11, 2018, there are now as few as 10 Code Talker veterans remaining of the original 400 that served in the war. His legacy will persist in the efforts he made in later years to spread awareness of the contribution made by Native Americans’ to the war, including a book he co-authored in 2013 about his experiences, Under the Eagle: Samuel Holiday, Code Talker.

Holiday frequently appeared at speaking engagements dressed in traditional Navajo clothing and spoke at several Utah schools to share the story of the Code Talkers with children.

Holiday passed away surrounded by his family in the nursing home where he spent his final years. He will be buried on the Kayenta, the Arizona Navajo Reservation, next to his late wife. His six children, 35 grandchildren, 30 great-grandchildren and 2 great-great-grandchildren will carry on the memory of his sacrifices made during the war and the tremendous impact of his work as a Code Talker.