Modern generals are granted access to a multitude of communication and information gathering technologies from satellite imaging to UAVs and infantry equipped with cameras. Ancient generals had none of these luxuries, and even methods of communication such as flag signaling were rare or nonexistent among some ancient cultures.

In large scale, ancient battles generals had to orchestrate the movements of tens of thousands of troops over thousands of acres of ground. Getting a wing of an army to change its course involved sending a rider. Often as battles wore on they created clouds of dust which obscured a commander’s view and night operations were incredibly difficult to manage as well.

To negate the difficulties of commanding thousands of troops at once, many generals organized a previously agreed upon and practiced deployment and attack. The Romans and many other cultures organized battle marches that led the army across the battlefield in three lines before turning towards the enemy and presenting an ordered battle formation.

Part of the reason the phalanx was so popular is that it required very little micromanagement during battle, this was the same for the Roman manipular formation, though movements such as when and how to deploy the Triarii were decided by the commander during battle.

With deploying and managing an army of thousands being such a difficult task, many generals stood out from the crowd because their leadership and grasp of command led to scores of victories. Generals such as Alexander the Great, Hanibal Barca, Scipio Africanus, and Julius Caesar are well known as the best ancient commanders, but how exactly did they command and influence the outcome in battles involving tens or hundreds of thousands of troops?

As mentioned above, it was very common to ensure that pre-battle formations were set up correctly, often with the best infantry in the center or the right flank (traditionally the general set up near his right flank) and cavalry often split equally on the wings. Great commanders could exploit this setup by changing small aspects of their formation to achieve victory.

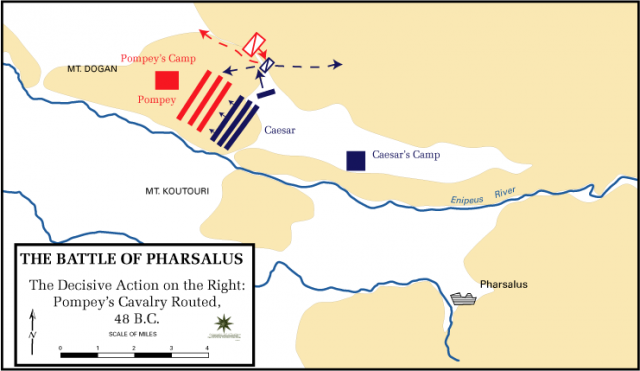

An excellent example of this is Caesar’s formation at Pharsalus. Facing an army with nearly twice the infantry and about five times more cavalry, Caesar knew he couldn’t win in a straight head on fight. Taking selected men from the traditional three lines, Caesar formed a small and concealed fourth line stationed on the right. The fourth line of infantry charged into the cavalry fight and helped Caesar’s 1-2,000 cavalry rout Pompey’s 5-8,000 cavalry. The victorious cavalry and fourth line were then free to attack the exposed flank of Pompey’s raw recruits and subsequently routed the whole army.

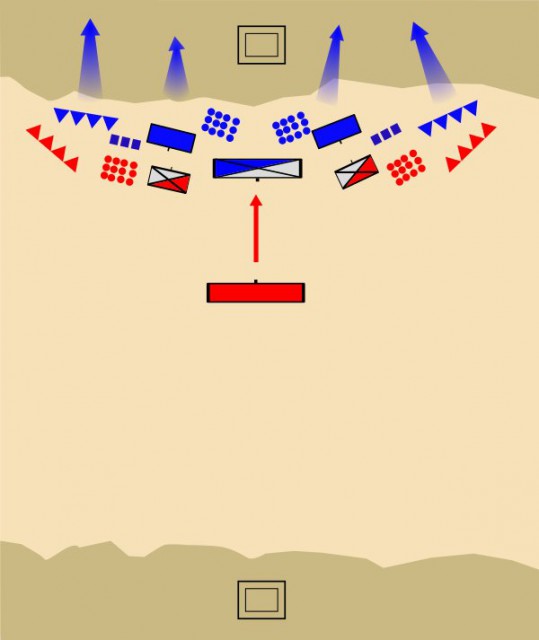

Another case of subtle formation shifting is Scipio Africanus deployment at the battle of Ilipa during the Iberian campaign of the Second Punic War. At this period it was more common for the most elite infantry to occupy the center and push through the middle of the enemy formation.

At Ilipa Scipio marched his men out in this battle formation, Romans in the center and his less reliable Spanish mercenaries on the wings, but did not attack and returned to camp. The opposing commander Hasdrubal matched this formation and day after day this repeated until Scipio marched out with one important change.

The Roman heavy infantry were now split between the wings, and the untested Spaniards took position in the center. Scipio ordered an attack before Hasdrubal had time to alter his deployment, and Scipio ordered the Spaniards to halt a short distance from Hasdrubal’s center while the Roman infantry charged against the wings. By doing this Scipio had his best infantry, his Romans, fighting Hasdrubal’s weaker wings while withholding his weakest Spanish mercenaries and preventing Hasdrubal’s elite infantry center from engaging.

Had Hasdrubal ordered his center to charge, they would have instantly been vulnerable to flanking on all sides by Scipio’s cavalry or the rear ranks of the Roman infantry, so they had no choice but to stay put. The Romans destroyed the flanks and collapsed towards the center and only after this were the Spaniards finally sent in to drive home the victory.

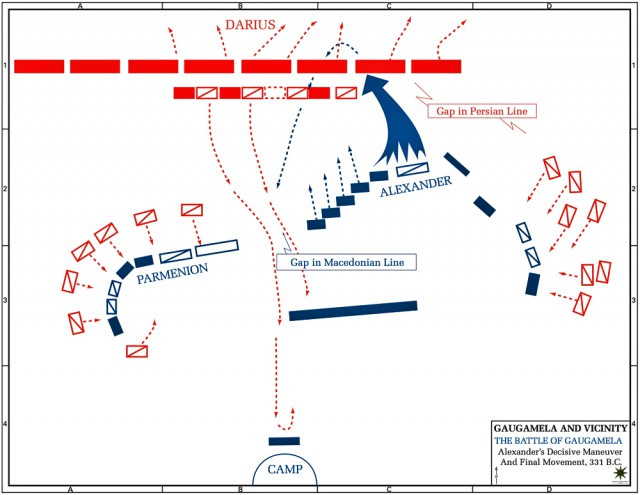

The subtle changing of formations often had great results, but it wasn’t the only way to lead troops. Sometimes a general could lead by example. Alexander the Great was a young and fit general who did not shy away from danger. Alexander had excellent commanders under him and the stability of the phalanx allowed him to lead his companion cavalry and wield them like a scalpel on the battlefield.

By leading a cavalry contingent Alexander was able to have complete control of a mobile unit that allowed him to go directly to important places in a battle and he could lead his cavalry charges exactly how he wanted to rather than sending an order to a subordinate hoping that they would know the best moment to charge.

At Gaugamela Alexander rode across the battlefield with his cavalry causing Darius to send troops to engage him as Darius feared that Alexander would lead the battle to unfavorable ground. Darius’ infantry left a gap when they moved to intercept Alexander and Alexander was able to turn and charge through this gap and attack the center of the Persian army, causing Darius to flee. By leading the charge himself Alexander ensured that his men would fight their hardest as their King was with them.

Alexander risked death at every battle and was wounded many times, but by fighting with his men, he ensured that they would fight to the death for him. This is not to devalue Alexander’s other strengths as he was the most complete general of all time and his leading from the front was but one of his many leadership skills.

Darius, on the other hand, relied on common tactics such as picking the field of battle and arraying his troops in a standard array to try to achieve a straightforward victory.

Caesar also knew that leading by example was an important motivator. Though he was nearly fifty by the battle of Alesia, he still personally led a counterattack when the Gauls breached his double walls encircling Alesia. Caesar donned his scarlet general’s cloak and was well seen by his troops. Seeing their general in the fight motivated the Romans and allowed them to push back the attackers.

These are but a few examples of how generals altered the standard methods of battle to get advantages in battles that were incredibly difficult to manage. These generals prevailed, but not every innovator was successful.