January 3rd, 2014, the Gloustershire Echo shares the story of Eric Cordingley. Cordingley was a POW and held captive in a camp in Singapore. The story of an Army rector from Leckhampton was published in a book titled, Down to Bedrock. The book includes entries from a diary Cordingley kept while he was held captive.

The reporter for the Echo was able to speak with the family and this is the story of their father, Eric Cordingley.

Eric Cordingley gave sermons that were awe inspiring and gave the other prisoners hope. However it was the numerous eulogies that Cordingley gave as chaplain while he was in the POW camp in Changi, Singapore. These eulogies served as a constant reminder of what could happen to them all.

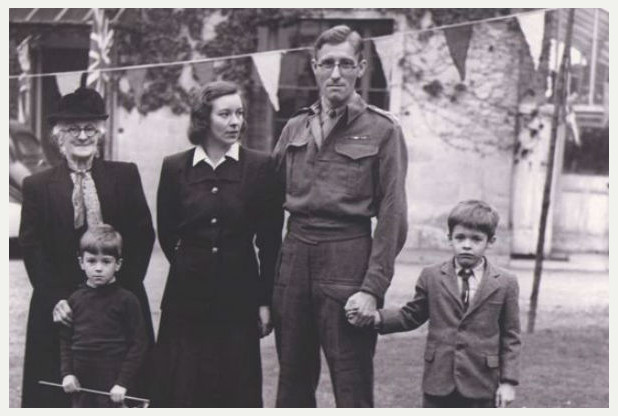

On October 14, 1945, Eric, an Army priest who was originally sent to defend the Far East from Japanese invasion, had returned safely to his rectory in Leckhampton. His parishioners were elated at his return and they raised bunting to toast his survival.

“I was not quite two when he went off to war (in 1941),” recalled his son, David, now 75, who can be seen holding his father’s hand in a photograph of his homecoming.

“My memories of how he was then are few or none at all but, when he returned home, I remember people treating him like a hero.”

When Eric made the front page news, he wore khakis and it was obvious that he endured disease and hunger for the three and a half years he was held captive.

“I do not wish to dwell on the horror of prison life,” Eric told the Echo upon his return. “No doubt, in the months to come, the full story will be given and become known to the world.”

His story has been published in a book which includes his diary and secret notes that were written while held captive.

“If his writings were discovered by the Japanese, he would surely have been tortured,” explained his daughter Louise Reynolds, who was born a year after her father was released.

A picture was taken inside one of the four chapels he built during imprisonment also gave his wife, Mary, hope that he would come home. “My mother saw the photo in a shop window in Cheltenham in September 1945,” Louise continued. “She recognized my father’s head underneath the lamp on the right hand side of the altar and realized that he’d survived.

“She said she couldn’t feel her legs as she walked home and that she was ‘walking on air’.”

Eric died in 1976 from cancer. He was only 65 years old. The doctors wrote that it was more than three and a half years of starvation.

Louise and her younger brother, Christopher, edited their father’s memoirs into a book. “Down to Bedrock” depicts the war rector through sketches that were drawn by his fellow prisoners during the time they were held captive between 1942 and 1945 when he was released.

“For me, it’s like a revival to learn so much more about my father,” said Louise, a 66-year-old couples’ counsellor.

“He couldn’t talk about it (his time as a Prisoner of War) but, to learn that his services kept him going and knowing that he helped so many people, was revelatory and makes me very proud.”

The book will be released a few days before the premier of the Railway Man, which stars Colin Firth. The movie illustrates the struggles prisoners endured while they worked on the infamous Death Railway during WWII.

The book also tells the story of Eric’s selflessness in Singapore as he and his comrades were sent to work on the Burma railway.

He could have returned back to the POW camp where life was marginally better; however, he remained with the surviving prisoners and prayed with them. “In the midst of the tropical heat and the lack of food, his faith kept people going,” Eric’s eldest son David continued.

“What was interesting to hear from his writings is that he had felt fairly useless on the battlefield and that it was only when they were made prisoners that he felt he had a job he could do by keeping their morale up.

“At St Peter’s Church, where my father was once rector in Leckhampton, it is strange to remember the weddings and funerals we saw in his absence during the war.

“After the war had ended, the Japanese PoWs weren’t released for a long time and all I can remember is the bunting and the ‘welcome home’ banners when my father finally returned. I was young but one was excited because everyone else was excited.

“I remember going down to the train station in the car and seeing his figure for the first time.

“I remember him looking quite drawn and gaunt although, from looking at his picture in the paper, you wouldn’t have known that he had suffered from malaria.

“We drove back through the village and we called at various cottages.

“It must have been incredible for him although I cannot put myself in his position. He faced death so many times in the PoW camp and here he was back home and alongside a family he had not seen for three and a half years.”