Typically, it can be said that the winners get to determine how history is told. In the case of the Crusades, however, that hasn’t been the case.

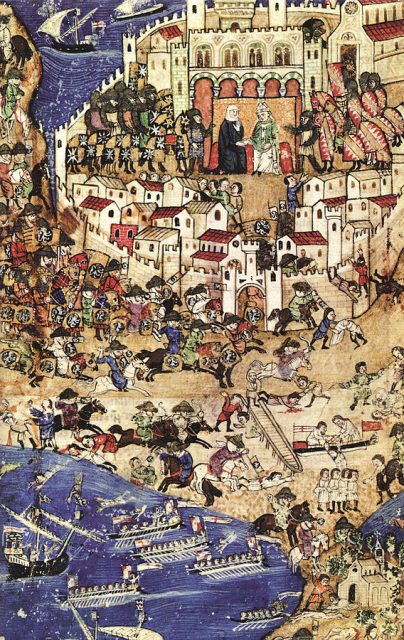

European Christians waged holy wars in the eastern Mediterranean during the 12th and 13th centuries until the Muslims kicked them out. But it is the stories told by medieval European chroniclers that have filtered through to the present day and form the basis of most modern histories of the Crusades.

So, how did Muslims view the invasions at the time? What did they think about the European invaders? It seems that they were not always so contentious about the Crusades and they basically considered the Europeans to be uncultured barbarians.

According to Suleiman Mourad, author of The Mosaic of Islam and a professor of religion at Smith College, had the Muslims written the histories of the Crusades, history wouldn’t focus on the wars and the bloodshed. Instead, there would be tales of coexistence, compromise, trade, scientific exchange, and love. There is, for example, Muslim poetry of the era that tells of mixed marriages.

Paul Cobb, author of Race for Paradise: An Islamic History of the Crusades and a professor of Islamic History at the University of Pennsylvania, said that Muslims don’t recognize the Crusades as a distinct occurrence. They were simply more aggressive acts from the western Christians.

Those aggressions don’t begin with Pope Urban’s speech in 1095 which rallied the crusaders. Instead, they see the attacks by the European Christians as beginning decades earlier. Western historians view the end of the Crusades as coinciding with the fall of Acre in 1291.

Muslim historians see the end of the invasions as not coming until the middle of the 15th century when Constantinople was conquered by the Ottoman empire.

At the beginning of the Crusades, the Muslim world was bigger than the Christian lands of the west. Islamic countries with Muslim rulers and that recognized Islamic law stretched from Portugal and Spain in the west to India in the east. In the north, they reached central Asia and extended to the horn of Africa in the south.

The core of the Islamic world at that time was divided into the Shi’ites and Sunni’s. Saladin was the first sultan of Egypt and Syria. He conquered Egypt first and then Syria and parts of Iraq.

After unifying the people in his empire, he eventually recaptured Jerusalem and pushed the Crusaders back to a strip along the Mediterranean.

There was a “golden age” in the Muslim world that lasted from the 9th to the 14th centuries during which various centers (like Baghdad, Damascus, and Cairo) were advancing mathematics, astronomy, and medicine.

According to Mourad, the primary accomplishments of the Muslims occurred when they took classical Greco-Roman-Byzantine ideas and re-thought them. In many areas of academics, the Muslims added to or provided corrections to the Western ideas.

At the time, the Islamic world was much bigger than the western world with bigger urban centers. For example, London and Paris combined were significantly smaller than many Islamic cities. Baghdad at the time likely had hundreds of thousands of people.

The Islamic world was also more diverse and wealthier than the western world. This led to a sense of trauma for the Muslims when the Christians invaded their lands. It seemed unthinkable that these people from the fringe of the known world could invade the divinely protected, culturally progressive and militarily mighty lands of the Muslims.

But as the Crusaders entered the Muslim lands, they were welcomed as any other visitors to the land. There are letters from Saladin to the king of Jerusalem, Baldwin III, that indicate their deep friendship and alliances.

So the era of the Crusades was in many ways the opposite of how the Muslim countries and Christian countries view each other today. Back then, the Europeans were viewed as the uncultured, religious extremists from exotic lands.