Efforts in researching information commemorating the Great War’s outbreak resulted to the uncovering of a young pilot’s diaries which highlighted the surprising cooperation which existed between German and British airmen during WWI.

Members of the Llangwm Local History Society made the discovery while they were going through log books and other diaries among their WWI collection.

Pilot William David Sambrook kept diaries for the duration of his assignment at Coudekerque airfield which was near Calais in 1916. The airfield where he was posted was just one of the many Allied and German airfields in that part of France and Belgium. His diaries revealed that there were times camaraderie between German and British pilots – two opposing sides of the war – took the lead over the hostilities raging on around them. The said diaries even suggested that German pilots gave warnings to their British counterparts where they planned on dropping bombs.

The diaries of the then 22-year-old WWI pilot recounted most of the daily bombing campaigns done on German-controlled aerodomes, docks and even Zeppelin sheds at Zeebrugge and Bruges. Young Sambrook went on to write in one of the pages of his diaries an incident on a certain day in May 1916 when one of his RANS comrade failed to return from a raid at an aerodome in Ostend. Talks started to circulate about his plane being salvaged from the sea by a Belgian trawler.

After a few days, when they still did not have any news about the missing pilot, one of Sambrook’s fellow pilot flew over a German airfield and dropped a note asking them if they have information about the missing pilot’s whereabouts. Surprisingly, they received a prompt reply from the Germans. The note which was also dropped from the air informed them that the aircraft indeed was shot down into the sea. Sambrook’s diaries went on to tell the whole story. According to the message airdropped by the Germans, the latter attempted to to rescue the plane but the pilot had already died when it was brought in. The dead British airman was buried with full military honors side by side with two comrades at the Marrakerke Cemetery. The entry in Sambrook’s diaries also noted that the message was accompanied with photos of the funeral and the grave.

There already had surfaced previous examples of how each opposing side treated the bodies of their victims with respect. However, a postscript to the note, written in the pilot’s diaries, seemed to acknowledge an unusual degree of comradeship among enemy pilots during the Great War.

According to the said postscript, there was a message, also in German, stating the name and place in German territory where British war planes could land on in case of engine trouble.

Imperial War Museum’s head of photographs Alan Wakefield stated in the report ran by WalesOnline that cooperation among fighters in the air was something more in common compared to having that same camaraderie among fighters on the ground as the battle in the latter was quick to escalate into an impersonal level. He further went on that there were even stories about how German pilots would drop messages with photos informing British airmen about downed WWI planes and their dead pilots asking for their names so they could make headstones. As a matter of fact, there had been an instance about how one German pilot dropped a note informing those on the ground to evacuate as he was about to drop a bomb.

However, he was a bit skeptical about the tip-off details accounted in Sambrook’s diaries about a safe landing place.

He said that such information was unanticipated. The German army, in general, were under strict orders to take British POWs so these safe landing places were not under the jurisdiction of the German air force during the Great War.

Wakefield then attributed the information written in the WWI pilot’s diaries to German humor further explaining that the British pilots wouldn’t have taken the information seriously.

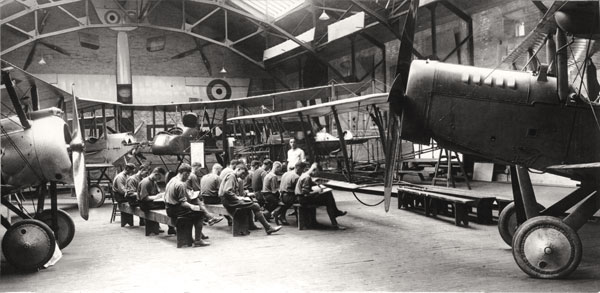

RNAS pilot William David Sambrook was given the Distinguished Service Medal for his bravery in the air in 1917. Approaching WWI’s end, he was one among the first airmen to try “deck flying”. He took off in Sopwith Pups and Camels from short platforms which were constructed on gun turrets. These were the aircraft carriers forerunners.

He survived his assignment in France and went on to work at the public health council in Westminster City Council after WWI ended. He then returned to Pembrokeshire after his public health career and went on to live with his sister in Deerland, Llangwm.

Richard Palmer, his nephew, still lives in the same house until today. He was the one who kept all his uncle’s diaries and logbooks safe. Mr. Palmer described Sambrook as a lovely man who gave him and his brother Twickenham rugby match programs and was their constant supplier of rugby boots. However, he kept mum about his war records.

Snippets from the Sambrook’s diaries along with a number of photographs will be put on exhibit funded by the Heritage Lottery in Llangwm in November.